Rutherfordium

| Rutherfordium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˌrʌðərˈfɔːrdiəm/ ⓘ | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mass number | [267] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Rutherfordium in the periodic table | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 104 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Group | group 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Period | period 7 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Block | d-block | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [Rn] 5f14 6d2 7s2[1][2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Electrons per shell | 2, 8, 18, 32, 32, 10, 2 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid (predicted)[1][2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 2400 K (2100 °C, 3800 °F) (predicted)[1][2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 5800 K (5500 °C, 9900 °F) (predicted)[1][2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 17 g/cm3 (predicted)[3][4] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | common: +4 (+3), (+4)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 150 pm (estimated)[2] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 157 pm (estimated)[1] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | synthetic | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | hexagonal close-packed (hcp) (predicted)[5] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 53850-36-5 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Naming | after Ernest Rutherford | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Joint Institute for Nuclear Research and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (1969) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Isotopes of rutherfordium | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Rutherfordium is a chemical element with the symbol Rf and atomic number 104, named after physicist Ernest Rutherford. As a synthetic element, it is not found in nature and can only be made in a particle accelerator. It is radioactive; the most stable known isotope, 267Rf, has a half-life of about 48 minutes.

In the periodic table, it is a d-block element and the second of the fourth-row transition elements. It is in period 7 and is a group 4 element. Chemistry experiments have confirmed that rutherfordium behaves as the heavier homolog to hafnium in group 4. The chemical properties of rutherfordium are characterized only partly. They compare well with the other group 4 elements, even though some calculations had indicated that the element might show significantly different properties due to relativistic effects.

In the 1960s, small amounts of rutherfordium were produced at Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in the Soviet Union and at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in California.[10] Priority of discovery and hence the name of the element was disputed between Soviet and American scientists, and it was not until 1997 that the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) established rutherfordium as the official name of the element.

Introduction

Superheavy elements, also known as transactinide elements, transactinides, or super-heavy elements, or superheavies for short, are the chemical elements with atomic number greater than 104.[11] The superheavy elements are those beyond the actinides in the periodic table; the last actinide is lawrencium (atomic number 103). By definition, superheavy elements are also transuranium elements, i.e., having atomic numbers greater than that of uranium (92). Depending on the definition of group 3 adopted by authors, lawrencium may also be included to complete the 6d series.[12][13][14][15]

Glenn T. Seaborg first proposed the actinide concept, which led to the acceptance of the actinide series. He also proposed a transactinide series ranging from element 104 to 121 and a superactinide series approximately spanning elements 122 to 153 (though more recent work suggests the end of the superactinide series to occur at element 157 instead). The transactinide seaborgium was named in his honor.[16][17]

Superheavies are radioactive and have only been obtained synthetically in laboratories. No macroscopic sample of any of these elements has ever been produced. Superheavies are all named after physicists and chemists or important locations involved in the synthesis of the elements.

IUPAC defines an element to exist if its lifetime is longer than 10−14 seconds, which is the time it takes for the atom to form an electron cloud.[18]

The known superheavies form part of the 6d and 7p series in the periodic table. Except for rutherfordium and dubnium (and lawrencium if it is included), even the longest-lived known isotopes of superheavies have half-lives of minutes or less. The element naming controversy involved elements 102–109. Some of these elements thus used systematic names for many years after their discovery was confirmed. (Usually the systematic names are replaced with permanent names proposed by the discoverers relatively soon after a discovery has been confirmed.)

Introduction

Synthesis of superheavy nuclei

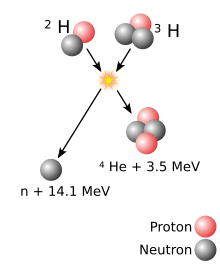

A superheavy[a] atomic nucleus is created in a nuclear reaction that combines two other nuclei of unequal size[b] into one; roughly, the more unequal the two nuclei in terms of mass, the greater the possibility that the two react.[24] The material made of the heavier nuclei is made into a target, which is then bombarded by the beam of lighter nuclei. Two nuclei can only fuse into one if they approach each other closely enough; normally, nuclei (all positively charged) repel each other due to electrostatic repulsion. The strong interaction can overcome this repulsion but only within a very short distance from a nucleus; beam nuclei are thus greatly accelerated in order to make such repulsion insignificant compared to the velocity of the beam nucleus.[25] The energy applied to the beam nuclei to accelerate them can cause them to reach speeds as high as one-tenth of the speed of light. However, if too much energy is applied, the beam nucleus can fall apart.[25]

Coming close enough alone is not enough for two nuclei to fuse: when two nuclei approach each other, they usually remain together for about 10−20 seconds and then part ways (not necessarily in the same composition as before the reaction) rather than form a single nucleus.[25][26] This happens because during the attempted formation of a single nucleus, electrostatic repulsion tears apart the nucleus that is being formed.[25] Each pair of a target and a beam is characterized by its cross section—the probability that fusion will occur if two nuclei approach one another expressed in terms of the transverse area that the incident particle must hit in order for the fusion to occur.[c] This fusion may occur as a result of the quantum effect in which nuclei can tunnel through electrostatic repulsion. If the two nuclei can stay close past that phase, multiple nuclear interactions result in redistribution of energy and an energy equilibrium.[25]

| External videos | |

|---|---|

The resulting merger is an excited state[29]—termed a compound nucleus—and thus it is very unstable.[25] To reach a more stable state, the temporary merger may fission without formation of a more stable nucleus.[30] Alternatively, the compound nucleus may eject a few neutrons, which would carry away the excitation energy; if the latter is not sufficient for a neutron expulsion, the merger would produce a gamma ray. This happens in about 10−16 seconds after the initial nuclear collision and results in creation of a more stable nucleus.[30] The definition by the IUPAC/IUPAP Joint Working Party (JWP) states that a chemical element can only be recognized as discovered if a nucleus of it has not decayed within 10−14 seconds. This value was chosen as an estimate of how long it takes a nucleus to acquire electrons and thus display its chemical properties.[31][d]

Decay and detection

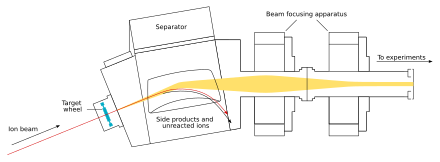

The beam passes through the target and reaches the next chamber, the separator; if a new nucleus is produced, it is carried with this beam.[33] In the separator, the newly produced nucleus is separated from other nuclides (that of the original beam and any other reaction products)[e] and transferred to a surface-barrier detector, which stops the nucleus. The exact location of the upcoming impact on the detector is marked; also marked are its energy and the time of the arrival.[33] The transfer takes about 10−6 seconds; in order to be detected, the nucleus must survive this long.[36] The nucleus is recorded again once its decay is registered, and the location, the energy, and the time of the decay are measured.[33]

Stability of a nucleus is provided by the strong interaction. However, its range is very short; as nuclei become larger, its influence on the outermost nucleons (protons and neutrons) weakens. At the same time, the nucleus is torn apart by electrostatic repulsion between protons, and its range is not limited.[37] Total binding energy provided by the strong interaction increases linearly with the number of nucleons, whereas electrostatic repulsion increases with the square of the atomic number, i.e. the latter grows faster and becomes increasingly important for heavy and superheavy nuclei.[38][39] Superheavy nuclei are thus theoretically predicted[40] and have so far been observed[41] to predominantly decay via decay modes that are caused by such repulsion: alpha decay and spontaneous fission.[f] Almost all alpha emitters have over 210 nucleons,[43] and the lightest nuclide primarily undergoing spontaneous fission has 238.[44] In both decay modes, nuclei are inhibited from decaying by corresponding energy barriers for each mode, but they can be tunneled through.[38][39]

Alpha particles are commonly produced in radioactive decays because the mass of an alpha particle per nucleon is small enough to leave some energy for the alpha particle to be used as kinetic energy to leave the nucleus.[46] Spontaneous fission is caused by electrostatic repulsion tearing the nucleus apart and produces various nuclei in different instances of identical nuclei fissioning.[39] As the atomic number increases, spontaneous fission rapidly becomes more important: spontaneous fission partial half-lives decrease by 23 orders of magnitude from uranium (element 92) to nobelium (element 102),[47] and by 30 orders of magnitude from thorium (element 90) to fermium (element 100).[48] The earlier liquid drop model thus suggested that spontaneous fission would occur nearly instantly due to disappearance of the fission barrier for nuclei with about 280 nucleons.[39][49] The later nuclear shell model suggested that nuclei with about 300 nucleons would form an island of stability in which nuclei will be more resistant to spontaneous fission and will primarily undergo alpha decay with longer half-lives.[39][49] Subsequent discoveries suggested that the predicted island might be further than originally anticipated; they also showed that nuclei intermediate between the long-lived actinides and the predicted island are deformed, and gain additional stability from shell effects.[50] Experiments on lighter superheavy nuclei,[51] as well as those closer to the expected island,[47] have shown greater than previously anticipated stability against spontaneous fission, showing the importance of shell effects on nuclei.[g]

Alpha decays are registered by the emitted alpha particles, and the decay products are easy to determine before the actual decay; if such a decay or a series of consecutive decays produces a known nucleus, the original product of a reaction can be easily determined.[h] (That all decays within a decay chain were indeed related to each other is established by the location of these decays, which must be in the same place.)[33] The known nucleus can be recognized by the specific characteristics of decay it undergoes such as decay energy (or more specifically, the kinetic energy of the emitted particle).[i] Spontaneous fission, however, produces various nuclei as products, so the original nuclide cannot be determined from its daughters.[j]

The information available to physicists aiming to synthesize a superheavy element is thus the information collected at the detectors: location, energy, and time of arrival of a particle to the detector, and those of its decay. The physicists analyze this data and seek to conclude that it was indeed caused by a new element and could not have been caused by a different nuclide than the one claimed. Often, provided data is insufficient for a conclusion that a new element was definitely created and there is no other explanation for the observed effects; errors in interpreting data have been made.[k]

History

Early predictions

The heaviest element known at the end of the 19th century was uranium, with an atomic mass of about 240 (now known to be 238) amu. Accordingly, it was placed in the last row of the periodic table; this fueled speculation about the possible existence of elements heavier than uranium and why A = 240 seemed to be the limit. Following the discovery of the noble gases, beginning with argon in 1895, the possibility of heavier members of the group was considered. Danish chemist Julius Thomsen proposed in 1895 the existence of a sixth noble gas with Z = 86, A = 212 and a seventh with Z = 118, A = 292, the last closing a 32-element period containing thorium and uranium.[62] In 1913, Swedish physicist Johannes Rydberg extended Thomsen's extrapolation of the periodic table to include even heavier elements with atomic numbers up to 460, but he did not believe that these superheavy elements existed or occurred in nature.[63]

In 1914, German physicist Richard Swinne proposed that elements heavier than uranium, such as those around Z = 108, could be found in cosmic rays. He suggested that these elements may not necessarily have decreasing half-lives with increasing atomic number, leading to speculation about the possibility of some longer-lived elements at Z = 98–102 and Z = 108–110 (though separated by short-lived elements). Swinne published these predictions in 1926, believing that such elements might exist in Earth's core, iron meteorites, or the ice caps of Greenland where they had been locked up from their supposed cosmic origin.[64]

Discoveries

Work performed from 1961 to 2013 at four labs – Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory in the US, the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research in the USSR (later Russia), the GSI Helmholtz Centre for Heavy Ion Research in Germany, and Riken in Japan – identified and confirmed the elements lawrencium to oganesson according to the criteria of the IUPAC–IUPAP Transfermium Working Groups and subsequent Joint Working Parties. These discoveries complete the seventh row of the periodic table. The next two elements, ununennium (Z = 119) and unbinilium (Z = 120), have not yet been synthesized. They would begin an eighth period.

List of elements

- 103 Lawrencium, Lr, for Ernest Lawrence; sometimes but not always included[12][13]

- 104 Rutherfordium, Rf, for Ernest Rutherford

- 105 Dubnium, Db, for the town of Dubna, near Moscow

- 106 Seaborgium, Sg, for Glenn T. Seaborg

- 107 Bohrium, Bh, for Niels Bohr

- 108 Hassium, Hs, for Hassia (Hesse), location of Darmstadt

- 109 Meitnerium, Mt, for Lise Meitner

- 110 Darmstadtium, Ds, for Darmstadt)

- 111 Roentgenium, Rg, for Wilhelm Röntgen

- 112 Copernicium, Cn, for Nicolaus Copernicus

- 113 Nihonium, Nh, for Nihon (Japan), location of the Riken institute

- 114 Flerovium, Fl, for Russian physicist Georgy Flyorov

- 115 Moscovium, Mc, for Moscow

- 116 Livermorium, Lv, for Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- 117 Tennessine, Ts, for Tennessee, location of Oak Ridge National Laboratory

- 118 Oganesson, Og, for Russian physicist Yuri Oganessian

Characteristics

Due to their short half-lives (for example, the most stable known isotope of seaborgium has a half-life of 14 minutes, and half-lives decrease with increasing atomic number) and the low yield of the nuclear reactions that produce them, new methods have had to be created to determine their gas-phase and solution chemistry based on very small samples of a few atoms each. Relativistic effects become very important in this region of the periodic table, causing the filled 7s orbitals, empty 7p orbitals, and filling 6d orbitals to all contract inward toward the atomic nucleus. This causes a relativistic stabilization of the 7s electrons and makes the 7p orbitals accessible in low excitation states.[17]

Elements 103 to 112, lawrencium to copernicium, form the 6d series of transition elements. Experimental evidence shows that elements 103–108 behave as expected for their position in the periodic table, as heavier homologs of lutetium through osmium. They are expected to have ionic radii between those of their 5d transition metal homologs and their actinide pseudohomologs: for example, Rf4+ is calculated to have ionic radius 76 pm, between the values for Hf4+ (71 pm) and Th4+ (94 pm). Their ions should also be less polarizable than those of their 5d homologs. Relativistic effects are expected to reach a maximum at the end of this series, at roentgenium (element 111) and copernicium (element 112). Nevertheless, many important properties of the transactinides are still not yet known experimentally, though theoretical calculations have been performed.[17]

Elements 113 to 118, nihonium to oganesson, should form a 7p series, completing the seventh period in the periodic table. Their chemistry will be greatly influenced by the very strong relativistic stabilization of the 7s electrons and a strong spin–orbit coupling effect "tearing" the 7p subshell apart into two sections, one more stabilized (7p1/2, holding two electrons) and one more destabilized (7p3/2, holding four electrons). Lower oxidation states should be stabilized here, continuing group trends, as both the 7s and 7p1/2 electrons exhibit the inert-pair effect. These elements are expected to largely continue to follow group trends, though with relativistic effects playing an increasingly larger role. In particular, the large 7p splitting results in an effective shell closure at flerovium (element 114) and a hence much higher than expected chemical activity for oganesson (element 118).[17]

Element 118 is the last element that has been synthesized. The next two elements, 119 and 120, should form an 8s series and be an alkali and alkaline earth metal respectively. The 8s electrons are expected to be relativistically stabilized, so that the trend toward higher reactivity down these groups will reverse and the elements will behave more like their period 5 homologs, rubidium and strontium. The 7p3/2 orbital is still relativistically destabilized, potentially giving these elements larger ionic radii and perhaps even being able to participate chemically. In this region, the 8p electrons are also relativistically stabilized, resulting in a ground-state 8s28p1 valence electron configuration for element 121. Large changes are expected to occur in the subshell structure in going from element 120 to element 121: for example, the radius of the 5g orbitals should drop drastically, from 25 Bohr units in element 120 in the excited [Og] 5g1 8s1 configuration to 0.8 Bohr units in element 121 in the excited [Og] 5g1 7d1 8s1 configuration, in a phenomenon called "radial collapse". Element 122 should add either a further 7d or a further 8p electron to element 121's electron configuration. Elements 121 and 122 should be similar to actinium and thorium respectively.[17]

At element 121, the superactinide series is expected to begin, when the 8s electrons and the filling 8p1/2, 7d3/2, 6f5/2, and 5g7/2 subshells determine the chemistry of these elements. Complete and accurate calculations are not available for elements beyond 123 because of the extreme complexity of the situation:[65] the 5g, 6f, and 7d orbitals should have about the same energy level, and in the region of element 160 the 9s, 8p3/2, and 9p1/2 orbitals should also be about equal in energy. This will cause the electron shells to mix so that the block concept no longer applies very well, and will also result in novel chemical properties that will make positioning these elements in a periodic table very difficult.[17]

Beyond superheavy elements

It has been suggested that elements beyond Z = 126 be called beyond superheavy elements.[66] Other sources refer to elements around Z = 164 as hyperheavy elements.[67]

See also

- Bose–Einstein condensate (also known as Superatom)

- Island of stability

Notes

- ^ In nuclear physics, an element is called heavy if its atomic number is high; lead (element 82) is one example of such a heavy element. The term "superheavy elements" typically refers to elements with atomic number greater than 103 (although there are other definitions, such as atomic number greater than 100[19] or 112;[20] sometimes, the term is presented an equivalent to the term "transactinide", which puts an upper limit before the beginning of the hypothetical superactinide series).[21] Terms "heavy isotopes" (of a given element) and "heavy nuclei" mean what could be understood in the common language—isotopes of high mass (for the given element) and nuclei of high mass, respectively.

- ^ In 2009, a team at the JINR led by Oganessian published results of their attempt to create hassium in a symmetric 136Xe + 136Xe reaction. They failed to observe a single atom in such a reaction, putting the upper limit on the cross section, the measure of probability of a nuclear reaction, as 2.5 pb.[22] In comparison, the reaction that resulted in hassium discovery, 208Pb + 58Fe, had a cross section of ~20 pb (more specifically, 19+19

-11 pb), as estimated by the discoverers.[23] - ^ The amount of energy applied to the beam particle to accelerate it can also influence the value of cross section. For example, in the 28

14Si

+ 1

0n

→ 28

13Al

+ 1

1p

reaction, cross section changes smoothly from 370 mb at 12.3 MeV to 160 mb at 18.3 MeV, with a broad peak at 13.5 MeV with the maximum value of 380 mb.[27] - ^ This figure also marks the generally accepted upper limit for lifetime of a compound nucleus.[32]

- ^ This separation is based on that the resulting nuclei move past the target more slowly then the unreacted beam nuclei. The separator contains electric and magnetic fields whose effects on a moving particle cancel out for a specific velocity of a particle.[34] Such separation can also be aided by a time-of-flight measurement and a recoil energy measurement; a combination of the two may allow to estimate the mass of a nucleus.[35]

- ^ Not all decay modes are caused by electrostatic repulsion. For example, beta decay is caused by the weak interaction.[42]

- ^ It was already known by the 1960s that ground states of nuclei differed in energy and shape as well as that certain magic numbers of nucleons corresponded to greater stability of a nucleus. However, it was assumed that there was no nuclear structure in superheavy nuclei as they were too deformed to form one.[47]

- ^ Since mass of a nucleus is not measured directly but is rather calculated from that of another nucleus, such measurement is called indirect. Direct measurements are also possible, but for the most part they have remained unavailable for superheavy nuclei.[52] The first direct measurement of mass of a superheavy nucleus was reported in 2018 at LBNL.[53] Mass was determined from the location of a nucleus after the transfer (the location helps determine its trajectory, which is linked to the mass-to-charge ratio of the nucleus, since the transfer was done in presence of a magnet).[54]

- ^ If the decay occurred in a vacuum, then since total momentum of an isolated system before and after the decay must be preserved, the daughter nucleus would also receive a small velocity. The ratio of the two velocities, and accordingly the ratio of the kinetic energies, would thus be inverse to the ratio of the two masses. The decay energy equals the sum of the known kinetic energy of the alpha particle and that of the daughter nucleus (an exact fraction of the former).[43] The calculations hold for an experiment as well, but the difference is that the nucleus does not move after the decay because it is tied to the detector.

- ^ Spontaneous fission was discovered by Soviet physicist Georgy Flerov,[55] a leading scientist at JINR, and thus it was a "hobbyhorse" for the facility.[56] In contrast, the LBL scientists believed fission information was not sufficient for a claim of synthesis of an element. They believed spontaneous fission had not been studied enough to use it for identification of a new element, since there was a difficulty of establishing that a compound nucleus had only ejected neutrons and not charged particles like protons or alpha particles.[32] They thus preferred to link new isotopes to the already known ones by successive alpha decays.[55]

- ^ For instance, element 102 was mistakenly identified in 1957 at the Nobel Institute of Physics in Stockholm, Stockholm County, Sweden.[57] There were no earlier definitive claims of creation of this element, and the element was assigned a name by its Swedish, American, and British discoverers, nobelium. It was later shown that the identification was incorrect.[58] The following year, RL was unable to reproduce the Swedish results and announced instead their synthesis of the element; that claim was also disproved later.[58] JINR insisted that they were the first to create the element and suggested a name of their own for the new element, joliotium;[59] the Soviet name was also not accepted (JINR later referred to the naming of the element 102 as "hasty").[60] This name was proposed to IUPAC in a written response to their ruling on priority of discovery claims of elements, signed 29 September 1992.[60] The name "nobelium" remained unchanged on account of its widespread usage.[61]

References

- ^ a b c d e "Rutherfordium". Royal Chemical Society. Retrieved 2019-09-21.

- ^ a b c d e f g Hoffman, Darleane C.; Lee, Diana M.; Pershina, Valeria (2006). "Transactinides and the future elements". In Morss; Edelstein, Norman M.; Fuger, Jean (eds.). The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (3rd ed.). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer Science+Business Media. ISBN 978-1-4020-3555-5.

- ^ Gyanchandani, Jyoti; Sikka, S. K. (10 May 2011). "Physical properties of the 6 d -series elements from density functional theory: Close similarity to lighter transition metals". Physical Review B. 83 (17): 172101. Bibcode:2011PhRvB..83q2101G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.83.172101.

- ^ Kratz; Lieser (2013). Nuclear and Radiochemistry: Fundamentals and Applications (3rd ed.). p. 631.

- ^ Östlin, A.; Vitos, L. (2011). "First-principles calculation of the structural stability of 6d transition metals". Physical Review B. 84 (11): 113104. Bibcode:2011PhRvB..84k3104O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.84.113104.

- ^ Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; Huang, W. J.; Naimi, S.; Audi, G. (2021). "The NUBASE2020 evaluation of nuclear properties" (PDF). Chinese Physics C. 45 (3): 030001. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/abddae.

- ^ Sonzogni, Alejandro. "Interactive Chart of Nuclides". National Nuclear Data Center: Brookhaven National Laboratory. Retrieved 2008-06-06.

- ^ Utyonkov, V. K.; Brewer, N. T.; Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Rykaczewski, K. P.; Abdullin, F. Sh.; Dimitriev, S. N.; Grzywacz, R. K.; Itkis, M. G.; Miernik, K.; Polyakov, A. N.; Roberto, J. B.; Sagaidak, R. N.; Shirokovsky, I. V.; Shumeiko, M. V.; Tsyganov, Yu. S.; Voinov, A. A.; Subbotin, V. G.; Sukhov, A. M.; Karpov, A. V.; Popeko, A. G.; Sabel'nikov, A. V.; Svirikhin, A. I.; Vostokin, G. K.; Hamilton, J. H.; Kovrinzhykh, N. D.; Schlattauer, L.; Stoyer, M. A.; Gan, Z.; Huang, W. X.; Ma, L. (30 January 2018). "Neutron-deficient superheavy nuclei obtained in the 240Pu+48Ca reaction". Physical Review C. 97 (14320): 014320. Bibcode:2018PhRvC..97a4320U. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.97.014320.

- ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Utyonkov, V. K.; Ibadullayev, D.; et al. (2022). "Investigation of 48Ca-induced reactions with 242Pu and 238U targets at the JINR Superheavy Element Factory". Physical Review C. 106 (24612): 024612. Bibcode:2022PhRvC.106b4612O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.106.024612. S2CID 251759318.

- ^ "Rutherfordium - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table". www.rsc.org. Retrieved 2016-12-09.

- ^ "Superheavy Element Discovery | Glenn T. Seaborg Institute". seaborg.llnl.gov. Retrieved 2024-09-02.

- ^ a b Neve, Francesco (2022). "Chemistry of superheavy transition metals". Journal of Coordination Chemistry. 75 (17–18): 2287–2307. doi:10.1080/00958972.2022.2084394. S2CID 254097024.

- ^ a b Mingos, Michael (1998). Essential Trends in Inorganic Chemistry. Oxford University Press. p. 387. ISBN 978-0-19-850109-1.

- ^ "A New Era of Discovery: the 2023 Long Range Plan for Nuclear Science" (PDF). U.S. Department of Energy. October 2023. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2023-10-05. Retrieved 20 October 2023 – via OSTI.

Superheavy elements (Z > 102) are teetering at the limits of mass and charge.

- ^ Kragh, Helge (2017). "The search for superheavy elements: Historical and philosophical perspectives". arXiv:1708.04064 [physics.hist-ph].

- ^ IUPAC Provisional Recommendations for the Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry (2004) (online draft of an updated version of the "Red Book" IR 3-6) Archived October 27, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e f Morss, Lester R.; Edelstein, Norman M.; Fuger, Jean, eds. (2006). The Chemistry of the Actinide and Transactinide Elements (3rd ed.). Dordrecht, The Netherlands: Springer. ISBN 978-1-4020-3555-5.

- ^ "Kernchemie". www.kernchemie.de.

- ^ Krämer, K. (2016). "Explainer: superheavy elements". Chemistry World. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ^ "Discovery of Elements 113 and 115". Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory. Archived from the original on 2015-09-11. Retrieved 2020-03-15.

- ^ Eliav, E.; Kaldor, U.; Borschevsky, A. (2018). "Electronic Structure of the Transactinide Atoms". In Scott, R. A. (ed.). Encyclopedia of Inorganic and Bioinorganic Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 1–16. doi:10.1002/9781119951438.eibc2632. ISBN 978-1-119-95143-8. S2CID 127060181.

- ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Dmitriev, S. N.; Yeremin, A. V.; et al. (2009). "Attempt to produce the isotopes of element 108 in the fusion reaction 136Xe + 136Xe". Physical Review C. 79 (2): 024608. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.79.024608. ISSN 0556-2813.

- ^ Münzenberg, G.; Armbruster, P.; Folger, H.; et al. (1984). "The identification of element 108" (PDF). Zeitschrift für Physik A. 317 (2): 235–236. Bibcode:1984ZPhyA.317..235M. doi:10.1007/BF01421260. S2CID 123288075. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 June 2015. Retrieved 20 October 2012.

- ^ Subramanian, S. (28 August 2019). "Making New Elements Doesn't Pay. Just Ask This Berkeley Scientist". Bloomberg Businessweek. Retrieved 2020-01-18.

- ^ a b c d e f Ivanov, D. (2019). "Сверхтяжелые шаги в неизвестное" [Superheavy steps into the unknown]. nplus1.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2020-02-02.

- ^ Hinde, D. (2017). "Something new and superheavy at the periodic table". The Conversation. Retrieved 2020-01-30.

- ^ Kern, B. D.; Thompson, W. E.; Ferguson, J. M. (1959). "Cross sections for some (n, p) and (n, α) reactions". Nuclear Physics. 10: 226–234. Bibcode:1959NucPh..10..226K. doi:10.1016/0029-5582(59)90211-1.

- ^ Wakhle, A.; Simenel, C.; Hinde, D. J.; et al. (2015). Simenel, C.; Gomes, P. R. S.; Hinde, D. J.; et al. (eds.). "Comparing Experimental and Theoretical Quasifission Mass Angle Distributions". European Physical Journal Web of Conferences. 86: 00061. Bibcode:2015EPJWC..8600061W. doi:10.1051/epjconf/20158600061. hdl:1885/148847. ISSN 2100-014X.

- ^ "Nuclear Reactions" (PDF). pp. 7–8. Retrieved 2020-01-27. Published as Loveland, W. D.; Morrissey, D. J.; Seaborg, G. T. (2005). "Nuclear Reactions". Modern Nuclear Chemistry. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. pp. 249–297. doi:10.1002/0471768626.ch10. ISBN 978-0-471-76862-3.

- ^ a b Krása, A. (2010). "Neutron Sources for ADS". Faculty of Nuclear Sciences and Physical Engineering. Czech Technical University in Prague: 4–8. S2CID 28796927.

- ^ Wapstra, A. H. (1991). "Criteria that must be satisfied for the discovery of a new chemical element to be recognized" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 63 (6): 883. doi:10.1351/pac199163060879. ISSN 1365-3075. S2CID 95737691.

- ^ a b Hyde, E. K.; Hoffman, D. C.; Keller, O. L. (1987). "A History and Analysis of the Discovery of Elements 104 and 105". Radiochimica Acta. 42 (2): 67–68. doi:10.1524/ract.1987.42.2.57. ISSN 2193-3405. S2CID 99193729.

- ^ a b c d Chemistry World (2016). "How to Make Superheavy Elements and Finish the Periodic Table [Video]". Scientific American. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- ^ Hoffman, Ghiorso & Seaborg 2000, p. 334.

- ^ Hoffman, Ghiorso & Seaborg 2000, p. 335.

- ^ Zagrebaev, Karpov & Greiner 2013, p. 3.

- ^ Beiser 2003, p. 432.

- ^ a b Pauli, N. (2019). "Alpha decay" (PDF). Introductory Nuclear, Atomic and Molecular Physics (Nuclear Physics Part). Université libre de Bruxelles. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- ^ a b c d e Pauli, N. (2019). "Nuclear fission" (PDF). Introductory Nuclear, Atomic and Molecular Physics (Nuclear Physics Part). Université libre de Bruxelles. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- ^ Staszczak, A.; Baran, A.; Nazarewicz, W. (2013). "Spontaneous fission modes and lifetimes of superheavy elements in the nuclear density functional theory". Physical Review C. 87 (2): 024320–1. arXiv:1208.1215. Bibcode:2013PhRvC..87b4320S. doi:10.1103/physrevc.87.024320. ISSN 0556-2813.

- ^ Audi et al. 2017, pp. 030001-129–030001-138.

- ^ Beiser 2003, p. 439.

- ^ a b Beiser 2003, p. 433.

- ^ Audi et al. 2017, p. 030001-125.

- ^ Aksenov, N. V.; Steinegger, P.; Abdullin, F. Sh.; et al. (2017). "On the volatility of nihonium (Nh, Z = 113)". The European Physical Journal A. 53 (7): 158. Bibcode:2017EPJA...53..158A. doi:10.1140/epja/i2017-12348-8. ISSN 1434-6001. S2CID 125849923.

- ^ Beiser 2003, p. 432–433.

- ^ a b c Oganessian, Yu. (2012). "Nuclei in the "Island of Stability" of Superheavy Elements". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 337 (1): 012005-1 – 012005-6. Bibcode:2012JPhCS.337a2005O. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/337/1/012005. ISSN 1742-6596.

- ^ Moller, P.; Nix, J. R. (1994). Fission properties of the heaviest elements (PDF). Dai 2 Kai Hadoron Tataikei no Simulation Symposium, Tokai-mura, Ibaraki, Japan. University of North Texas. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- ^ a b Oganessian, Yu. Ts. (2004). "Superheavy elements". Physics World. 17 (7): 25–29. doi:10.1088/2058-7058/17/7/31. Retrieved 2020-02-16.

- ^ Schädel, M. (2015). "Chemistry of the superheavy elements". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 373 (2037): 20140191. Bibcode:2015RSPTA.37340191S. doi:10.1098/rsta.2014.0191. ISSN 1364-503X. PMID 25666065.

- ^ Hulet, E. K. (1989). Biomodal spontaneous fission. 50th Anniversary of Nuclear Fission, Leningrad, USSR. Bibcode:1989nufi.rept...16H.

- ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Rykaczewski, K. P. (2015). "A beachhead on the island of stability". Physics Today. 68 (8): 32–38. Bibcode:2015PhT....68h..32O. doi:10.1063/PT.3.2880. ISSN 0031-9228. OSTI 1337838. S2CID 119531411.

- ^ Grant, A. (2018). "Weighing the heaviest elements". Physics Today. doi:10.1063/PT.6.1.20181113a. S2CID 239775403.

- ^ Howes, L. (2019). "Exploring the superheavy elements at the end of the periodic table". Chemical & Engineering News. Retrieved 2020-01-27.

- ^ a b Robinson, A. E. (2019). "The Transfermium Wars: Scientific Brawling and Name-Calling during the Cold War". Distillations. Retrieved 2020-02-22.

- ^ "Популярная библиотека химических элементов. Сиборгий (экавольфрам)" [Popular library of chemical elements. Seaborgium (eka-tungsten)]. n-t.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 2020-01-07. Reprinted from "Экавольфрам" [Eka-tungsten]. Популярная библиотека химических элементов. Серебро – Нильсборий и далее [Popular library of chemical elements. Silver through nielsbohrium and beyond] (in Russian). Nauka. 1977.

- ^ "Nobelium - Element information, properties and uses | Periodic Table". Royal Society of Chemistry. Retrieved 2020-03-01.

- ^ a b Kragh 2018, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Kragh 2018, p. 40.

- ^ a b Ghiorso, A.; Seaborg, G. T.; Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; et al. (1993). "Responses on the report 'Discovery of the Transfermium elements' followed by reply to the responses by Transfermium Working Group" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 65 (8): 1815–1824. doi:10.1351/pac199365081815. S2CID 95069384. Archived (PDF) from the original on 25 November 2013. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ Commission on Nomenclature of Inorganic Chemistry (1997). "Names and symbols of transfermium elements (IUPAC Recommendations 1997)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 69 (12): 2471–2474. doi:10.1351/pac199769122471.

- ^ Kragh 2018, p. 6

- ^ Kragh 2018, p. 7

- ^ Kragh 2018, p. 10

- ^ van der Schoor, K. (2016). Electronic structure of element 123 (PDF) (Thesis). Rijksuniversiteit Groningen.

- ^ Hofmann, Sigurd (2019). "Synthesis and properties of isotopes of the transactinides". Radiochimica Acta. 107 (9–11): 879–915. doi:10.1515/ract-2019-3104. S2CID 203848120.

- ^ Laforge, Evan; Price, Will; Rafelski, Johann (2023). "Superheavy elements and ultradense matter". The European Physical Journal Plus. 138 (9): 812. arXiv:2306.11989. Bibcode:2023EPJP..138..812L. doi:10.1140/epjp/s13360-023-04454-8.

Bibliography

- Audi, G.; Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; et al. (2017). "The NUBASE2016 evaluation of nuclear properties". Chinese Physics C. 41 (3). 030001. Bibcode:2017ChPhC..41c0001A. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/41/3/030001.

pp. 030001-1–030001-17, pp. 030001-18–030001-138, Table I. The NUBASE2016 table of nuclear and decay properties - Beiser, A. (2003). Concepts of modern physics (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-244848-1. OCLC 48965418.

- Hoffman, D. C.; Ghiorso, A.; Seaborg, G. T. (2000). The Transuranium People: The Inside Story. World Scientific. ISBN 978-1-78-326244-1.

- Kragh, H. (2018). From Transuranic to Superheavy Elements: A Story of Dispute and Creation. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-75813-8.

- Zagrebaev, V.; Karpov, A.; Greiner, W. (2013). "Future of superheavy element research: Which nuclei could be synthesized within the next few years?". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 420 (1). 012001. arXiv:1207.5700. Bibcode:2013JPhCS.420a2001Z. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/420/1/012001. ISSN 1742-6588.

History

Discovery

Rutherfordium was reportedly first detected in 1964 at the Joint Institute for Nuclear Research at Dubna (Soviet Union at the time). Researchers there bombarded a plutonium-242 target with neon-22 ions and separated the reaction products by gradient thermochromatography after conversion to chlorides by interaction with ZrCl4. The team identified spontaneous fission activity contained within a volatile chloride portraying eka-hafnium properties. Though a half-life was not accurately determined, later calculations indicated that the product was most likely rutherfordium-259 (259Rf in standard notation):[1]

- 242

94Pu

+ 22

10Ne

→ 264−x

104Rf

→ 264−x

104Rf

Cl4

In 1969, researchers at University of California, Berkeley conclusively synthesized the element by bombarding a californium-249 target with carbon-12 ions and measured the alpha decay of 257Rf, correlated with the daughter decay of nobelium-253:[2]

- 249

98Cf

+ 12

6C

→ 257

104Rf

+ 4

n

The American synthesis was independently confirmed in 1973 and secured the identification of rutherfordium as the parent by the observation of K-alpha X-rays in the elemental signature of the 257Rf decay product, nobelium-253.[3]

Naming controversy

As a consequence of the initial competing claims of discovery, an element naming controversy arose. Since the Soviets claimed to have first detected the new element they suggested the name kurchatovium (Ku) in honor of Igor Kurchatov (1903–1960), former head of Soviet nuclear research. This name had been used in books of the Soviet Bloc as the official name of the element. The Americans, however, proposed rutherfordium (Rf) for the new element to honor New Zealand physicist Ernest Rutherford, who is known as the "father" of nuclear physics.[4] In 1992, the IUPAC/IUPAP Transfermium Working Group (TWG) assessed the claims of discovery and concluded that both teams provided contemporaneous evidence to the synthesis of element 104 and that credit should be shared between the two groups.[1]

The American group wrote a scathing response to the findings of the TWG, stating that they had given too much emphasis on the results from the Dubna group. In particular they pointed out that the Russian group had altered the details of their claims several times over a period of 20 years, a fact that the Russian team does not deny. They also stressed that the TWG had given too much credence to the chemistry experiments performed by the Russians and accused the TWG of not having appropriately qualified personnel on the committee. The TWG responded by saying that this was not the case and having assessed each point raised by the American group said that they found no reason to alter their conclusion regarding priority of discovery.[5] The IUPAC finally used the name suggested by the American team (rutherfordium).[6]

The International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) adopted unnilquadium (Unq) as a temporary, systematic element name, derived from the Latin names for digits 1, 0, and 4. In 1994, IUPAC suggested a set of names for elements 104 through 109, in which dubnium (Db) became element 104 and rutherfordium became element 106.[7] This recommendation was criticized by the American scientists for several reasons. Firstly, their suggestions were scrambled: the names rutherfordium and hahnium, originally suggested by Berkeley for elements 104 and 105, were respectively reassigned to elements 106 and 108. Secondly, elements 104 and 105 were given names favored by JINR, despite earlier recognition of LBL as an equal co-discoverer for both of them. Thirdly and most importantly, IUPAC rejected the name seaborgium for element 106, having just approved a rule that an element could not be named after a living person, even though the IUPAC had given the LBNL team the sole credit for its discovery.[8] In 1997, IUPAC renamed elements 104 to 109, and gave element 104 the current name rutherfordium. The name dubnium was given to element 105 at the same time.[6]

Isotopes

| Isotope |

Half-life [9] |

Decay mode[9] |

Discovery year |

Reaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 253Rf | 48 μs | α, SF | 1994 | 204Pb(50Ti,n)[10] |

| 254Rf | 23 μs | SF | 1994 | 206Pb(50Ti,2n)[10] |

| 255Rf | 2.3 s | ε?, α, SF | 1974 | 207Pb(50Ti,2n)[11] |

| 256Rf | 6.4 ms | α, SF | 1974 | 208Pb(50Ti,2n)[11] |

| 257Rf | 4.7 s | ε, α, SF | 1969 | 249Cf(12C,4n)[2] |

| 257mRf | 4.1 s | ε, α, SF | 1969 | 249Cf(12C,4n)[2] |

| 258Rf | 14.7 ms | α, SF | 1969 | 249Cf(13C,4n)[2] |

| 259Rf | 3.2 s | α, SF | 1969 | 249Cf(13C,3n)[2] |

| 259mRf | 2.5 s | ε | 1969 | 249Cf(13C,3n)[2] |

| 260Rf | 21 ms | α, SF | 1969 | 248Cm(16O,4n)[1] |

| 261Rf | 78 s | α, SF | 1970 | 248Cm(18O,5n)[12] |

| 261mRf | 4 s | ε, α, SF | 2001 | 244Pu(22Ne,5n)[13] |

| 262Rf | 2.3 s | α, SF | 1996 | 244Pu(22Ne,4n)[14] |

| 263Rf | 15 min | α, SF | 1999 | 263Db( e− , ν e)[15] |

| 263mRf ? | 8 s | α, SF | 1999 | 263Db( e− , ν e)[15] |

| 265Rf | 1.1 min[16] | SF | 2010 | 269Sg(—,α)[17] |

| 266Rf | 23 s? | SF | 2007? | 266Db( e− , ν e)?[18][19] |

| 267Rf | 48 min[20] | SF | 2004 | 271Sg(—,α)[21] |

| 268Rf | 1.4 s? | SF | 2004? | 268Db( e− , ν e)?[19][22] |

| 270Rf | 20 ms?[23] | SF | 2010? | 270Db( e− , ν e)?[24] |

Rutherfordium has no stable or naturally occurring isotopes. Several radioactive isotopes have been synthesized in the laboratory, either by fusing two atoms or by observing the decay of heavier elements. Sixteen different isotopes have been reported with atomic masses from 253 to 270 (with the exceptions of 264 and 269). Most of these decay predominantly through spontaneous fission pathways.[9][25]

Stability and half-lives

Out of isotopes whose half-lives are known, the lighter isotopes usually have shorter half-lives; half-lives of under 50 μs for 253Rf and 254Rf were observed. 256Rf, 258Rf, 260Rf are more stable at around 10 ms, 255Rf, 257Rf, 259Rf, and 262Rf live between 1 and 5 seconds, and 261Rf, 265Rf, and 263Rf are more stable, at around 1.1, 1.5, and 10 minutes respectively. The heaviest isotopes are the most stable, with 267Rf having a measured half-life of about 48 minutes.[20]

The lightest isotopes were synthesized by direct fusion between two lighter nuclei and as decay products. The heaviest isotope produced by direct fusion is 262Rf; heavier isotopes have only been observed as decay products of elements with larger atomic numbers. The heavy isotopes 266Rf and 268Rf have also been reported as electron capture daughters of the dubnium isotopes 266Db and 268Db, but have short half-lives to spontaneous fission. It seems likely that the same is true for 270Rf, a possible daughter of 270Db.[24] These three isotopes remain unconfirmed.

In 1999, American scientists at the University of California, Berkeley, announced that they had succeeded in synthesizing three atoms of 293Og.[26] These parent nuclei were reported to have successively emitted seven alpha particles to form 265Rf nuclei, but their claim was retracted in 2001.[27] This isotope was later discovered in 2010 as the final product in the decay chain of 285Fl.[16][17]

Predicted properties

Very few properties of rutherfordium or its compounds have been measured; this is due to its extremely limited and expensive production[28] and the fact that rutherfordium (and its parents) decays very quickly. A few singular chemistry-related properties have been measured, but properties of rutherfordium metal remain unknown and only predictions are available.

Chemical

Rutherfordium is the first transactinide element and the second member of the 6d series of transition metals. Calculations on its ionization potentials, atomic radius, as well as radii, orbital energies, and ground levels of its ionized states are similar to that of hafnium and very different from that of lead. Therefore, it was concluded that rutherfordium's basic properties will resemble those of other group 4 elements, below titanium, zirconium, and hafnium.[15][29] Some of its properties were determined by gas-phase experiments and aqueous chemistry. The oxidation state +4 is the only stable state for the latter two elements and therefore rutherfordium should also exhibit a stable +4 state.[29] In addition, rutherfordium is also expected to be able to form a less stable +3 state.[30] The standard reduction potential of the Rf4+/Rf couple is predicted to be higher than −1.7 V.[31]

Initial predictions of the chemical properties of rutherfordium were based on calculations which indicated that the relativistic effects on the electron shell might be strong enough that the 7p orbitals would have a lower energy level than the 6d orbitals, giving it a valence electron configuration of 6d1 7s2 7p1 or even 7s2 7p2, therefore making the element behave more like lead than hafnium. With better calculation methods and experimental studies of the chemical properties of rutherfordium compounds it could be shown that this does not happen and that rutherfordium instead behaves like the rest of the group 4 elements.[30][29] Later it was shown in ab initio calculations with the high level of accuracy[32][33][34] that the Rf atom has the ground state with the 6d2 7s2 valence configuration and the low-lying excited 6d1 7s2 7p1 state with the excitation energy of only 0.3–0.5 eV.

In an analogous manner to zirconium and hafnium, rutherfordium is projected to form a very stable, refractory oxide, RfO2. It reacts with halogens to form tetrahalides, RfX4, which hydrolyze on contact with water to form oxyhalides RfOX2. The tetrahalides are volatile solids existing as monomeric tetrahedral molecules in the vapor phase.[29]

In the aqueous phase, the Rf4+ ion hydrolyzes less than titanium(IV) and to a similar extent as zirconium and hafnium, thus resulting in the RfO2+ ion. Treatment of the halides with halide ions promotes the formation of complex ions. The use of chloride and bromide ions produces the hexahalide complexes RfCl2−

6 and RfBr2−

6. For the fluoride complexes, zirconium and hafnium tend to form hepta- and octa- complexes. Thus, for the larger rutherfordium ion, the complexes RfF2−

6, RfF3−

7 and RfF4−

8 are possible.[29]

Physical and atomic

Rutherfordium is expected to be a solid under normal conditions and have a hexagonal close-packed crystal structure (c/a = 1.61), similar to its lighter congener hafnium.[35] It should be a metal with density ~17 g/cm3.[36][37] The atomic radius of rutherfordium is expected to be ~150 pm. Due to relativistic stabilization of the 7s orbital and destabilization of the 6d orbital, Rf+ and Rf2+ ions are predicted to give up 6d electrons instead of 7s electrons, which is the opposite of the behavior of its lighter homologs.[30] When under high pressure (variously calculated as 72 or ~50 GPa), rutherfordium is expected to transition to body-centered cubic crystal structure; hafnium transforms to this structure at 71±1 GPa, but has an intermediate ω structure that it transforms to at 38±8 GPa that should be lacking for rutherfordium.[38]

Experimental chemistry

Gas phase

Early work on the study of the chemistry of rutherfordium focused on gas thermochromatography and measurement of relative deposition temperature adsorption curves. The initial work was carried out at Dubna in an attempt to reaffirm their discovery of the element. Recent work is more reliable regarding the identification of the parent rutherfordium radioisotopes. The isotope 261mRf has been used for these studies,[29] though the long-lived isotope 267Rf (produced in the decay chain of 291Lv, 287Fl, and 283Cn) may be advantageous for future experiments.[39] The experiments relied on the expectation that rutherfordium would begin the new 6d series of elements and should therefore form a volatile tetrachloride due to the tetrahedral nature of the molecule.[29][40][41] Rutherfordium(IV) chloride is more volatile than its lighter homologue hafnium(IV) chloride (HfCl4) because its bonds are more covalent.[30]

A series of experiments confirmed that rutherfordium behaves as a typical member of group 4, forming a tetravalent chloride (RfCl4) and bromide (RfBr4) as well as an oxychloride (RfOCl2). A decreased volatility was observed for RfCl

4 when potassium chloride is provided as the solid phase instead of gas, highly indicative of the formation of nonvolatile K

2RfCl

6 mixed salt.[15][29][42]

Aqueous phase

Rutherfordium is expected to have the electron configuration [Rn]5f14 6d2 7s2 and therefore behave as the heavier homologue of hafnium in group 4 of the periodic table. It should therefore readily form a hydrated Rf4+ ion in strong acid solution and should readily form complexes in hydrochloric acid, hydrobromic or hydrofluoric acid solutions.[29]

The most conclusive aqueous chemistry studies of rutherfordium have been performed by the Japanese team at Japan Atomic Energy Research Institute using the isotope 261mRf. Extraction experiments from hydrochloric acid solutions using isotopes of rutherfordium, hafnium, zirconium, as well as the pseudo-group 4 element thorium have proved a non-actinide behavior for rutherfordium. A comparison with its lighter homologues placed rutherfordium firmly in group 4 and indicated the formation of a hexachlororutherfordate complex in chloride solutions, in a manner similar to hafnium and zirconium.[29][43]

- 261m

Rf4+

+ 6 Cl−

→ [261mRfCl

6]2−

Very similar results were observed in hydrofluoric acid solutions. Differences in the extraction curves were interpreted as a weaker affinity for fluoride ion and the formation of the hexafluororutherfordate ion, whereas hafnium and zirconium ions complex seven or eight fluoride ions at the concentrations used:[29]

- 261m

Rf4+

+ 6 F−

→ [261mRfF

6]2−

Experiments performed in mixed sulfuric and nitric acid solutions shows that rutherfordium has a much weaker affinity towards forming sulfate complexes than hafnium. This result is in agreement with predictions, which expect rutherfordium complexes to be less stable than those of zirconium and hafnium because of a smaller ionic contribution to the bonding. This arises because rutherfordium has a larger ionic radius (76 pm) than zirconium (71 pm) and hafnium (72 pm), and also because of relativistic stabilisation of the 7s orbital and destabilisation and spin–orbit splitting of the 6d orbitals.[44]

Coprecipitation experiments performed in 2021 studied rutherfordium's behaviour in basic solution containing ammonia or sodium hydroxide, using zirconium, hafnium, and thorium as comparisons. It was found that rutherfordium does not strongly coordinate with ammonia and instead coprecipitates out as a hydroxide, which is probably Rf(OH)4.[45]

Notes

References

- ^ a b c Barber, R. C.; Greenwood, N. N.; Hrynkiewicz, A. Z.; Jeannin, Y. P.; Lefort, M.; Sakai, M.; Ulehla, I.; Wapstra, A. P.; Wilkinson, D. H. (1993). "Discovery of the transfermium elements. Part II: Introduction to discovery profiles. Part III: Discovery profiles of the transfermium elements". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 65 (8): 1757–1814. doi:10.1351/pac199365081757. S2CID 195819585.

- ^ a b c d e f Ghiorso, A.; Nurmia, M.; Harris, J.; Eskola, K.; Eskola, P. (1969). "Positive Identification of Two Alpha-Particle-Emitting Isotopes of Element 104" (PDF). Physical Review Letters. 22 (24): 1317–1320. Bibcode:1969PhRvL..22.1317G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.22.1317.

- ^ Bemis, C. E.; Silva, R.; Hensley, D.; Keller, O.; Tarrant, J.; Hunt, L.; Dittner, P.; Hahn, R.; Goodman, C. (1973). "X-Ray Identification of Element 104". Physical Review Letters. 31 (10): 647–650. Bibcode:1973PhRvL..31..647B. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.31.647.

- ^ "Rutherfordium". Rsc.org. Retrieved 2010-09-04.

- ^ Ghiorso, A.; Seaborg, G. T.; Organessian, Yu. Ts.; Zvara, I.; Armbruster, P.; Hessberger, F. P.; Hofmann, S.; Leino, M.; Munzenberg, G.; Reisdorf, W.; Schmidt, K.-H. (1993). "Responses on 'Discovery of the transfermium elements' by Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory, California; Joint Institute for Nuclear Research, Dubna; and Gesellschaft fur Schwerionenforschung, Darmstadt followed by reply to responses by the Transfermium Working Group". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 65 (8): 1815–1824. doi:10.1351/pac199365081815.

- ^ a b "Names and symbols of transfermium elements (IUPAC Recommendations 1997)". Pure and Applied Chemistry. 69 (12): 2471–2474. 1997. doi:10.1351/pac199769122471.

- ^ "Names and symbols of transfermium elements (IUPAC Recommendations 1994)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 66 (12): 2419–2421. 1994. doi:10.1351/pac199466122419. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 22, 2017. Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ Yarris, L. (1994). "Naming of element 106 disputed by international committee". Retrieved September 7, 2016.

- ^ a b c Cite warning:

<ref>tag with namenuclidetablecannot be previewed because it is defined outside the current section or not defined in this article at all. - ^ a b Heßberger, F. P.; Hofmann, S.; Ninov, V.; Armbruster, P.; Folger, H.; Münzenberg, G.; Schött, H. J.; Popeko, A. K.; et al. (1997). "Spontaneous fission and alpha-decay properties of neutron deficient isotopes 257−253104 and 258106". Zeitschrift für Physik A. 359 (4): 415. Bibcode:1997ZPhyA.359..415A. doi:10.1007/s002180050422. S2CID 121551261.

- ^ a b Heßberger, F. P.; Hofmann, S.; Ackermann, D.; Ninov, V.; Leino, M.; Münzenberg, G.; Saro, S.; Lavrentev, A.; et al. (2001). "Decay properties of neutron-deficient isotopes 256,257Db, 255Rf, 252,253Lr". European Physical Journal A. 12 (1): 57–67. Bibcode:2001EPJA...12...57H. doi:10.1007/s100500170039. S2CID 117896888.

- ^ Ghiorso, A.; Nurmia, M.; Eskola, K.; Eskola P. (1970). "261Rf; new isotope of element 104". Physics Letters B. 32 (2): 95–98. Bibcode:1970PhLB...32...95G. doi:10.1016/0370-2693(70)90595-2.

- ^ Dressler, R. & Türler, A. Evidence for isomeric states in 261Rf (PDF) (Report). PSI Annual Report 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- ^ Lane, M. R.; Gregorich, K.; Lee, D.; Mohar, M.; Hsu, M.; Kacher, C.; Kadkhodayan, B.; Neu, M.; et al. (1996). "Spontaneous fission properties of 104262Rf". Physical Review C. 53 (6): 2893–2899. Bibcode:1996PhRvC..53.2893L. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.53.2893. PMID 9971276.

- ^ a b c d Kratz, J. V.; Nähler, A.; Rieth, U.; Kronenberg, A.; Kuczewski, B.; Strub, E.; Brüchle, W.; Schädel, M.; et al. (2003). "An EC-branch in the decay of 27-s263Db: Evidence for the new isotope263Rf" (PDF). Radiochim. Acta. 91 (1–2003): 59–62. doi:10.1524/ract.91.1.59.19010. S2CID 96560109. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-25.

- ^ a b Cite warning:

<ref>tag with namePuCa2017cannot be previewed because it is defined outside the current section or not defined in this article at all. - ^ a b Ellison, P.; Gregorich, K.; Berryman, J.; Bleuel, D.; Clark, R.; Dragojević, I.; Dvorak, J.; Fallon, P.; Fineman-Sotomayor, C.; et al. (2010). "New Superheavy Element Isotopes: 242Pu(48Ca,5n)285114". Physical Review Letters. 105 (18): 182701. Bibcode:2010PhRvL.105r2701E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.105.182701. PMID 21231101.

- ^ Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; et al. (2007). "Synthesis of the isotope 282113 in the Np237+Ca48 fusion reaction". Physical Review C. 76 (1): 011601. Bibcode:2007PhRvC..76a1601O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.76.011601.

- ^ a b Oganessian, Yuri (8 February 2012). "Nuclei in the "Island of Stability" of Superheavy Elements". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 337 (1). IOP Publishing: 012005. Bibcode:2012JPhCS.337a2005O. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/337/1/012005. ISSN 1742-6596.

- ^ a b Oganessian, Yu. Ts.; Utyonkov, V. K.; Ibadullayev, D.; et al. (2022). "Investigation of 48Ca-induced reactions with 242Pu and 238U targets at the JINR Superheavy Element Factory". Physical Review C. 106 (24612). Bibcode:2022PhRvC.106b4612O. doi:10.1103/PhysRevC.106.024612. S2CID 251759318.

- ^ Hofmann, S. (2009). "Superheavy Elements". The Euroschool Lectures on Physics with Exotic Beams, Vol. III Lecture Notes in Physics. Lecture Notes in Physics. Vol. 764. Springer. pp. 203–252. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-85839-3_6. ISBN 978-3-540-85838-6.

- ^ Dmitriev, S N; Eichler, R; Bruchertseifer, H; Itkis, M G; Utyonkov, V K; Aggeler, H W; Lobanov, Yu V; Sokol, E A; Oganessian, Yu T; Wild, J F; Aksenov, N V; Vostokin, G K; Shishkin, S V; Tsyganov, Yu S; Stoyer, M A; Kenneally, J M; Shaughnessy, D A; Schumann, D; Eremin, A V; Hussonnois, M; Wilk, P A; Chepigin, V I (15 October 2004). "Chemical Identification of Dubnium as a Decay Product of Element 115 Produced in the Reaction 48Ca+243Am". CERN Document Server. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ Fritz Peter Heßberger. "Exploration of Nuclear Structure and Decay of Heaviest Elements at GSI - SHIP". agenda.infn.it. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ^ a b Stock, Reinhard (13 September 2013). Encyclopedia of Nuclear Physics and its Applications. John Wiley & Sons. p. 305. ISBN 978-3-527-64926-6. OCLC 867630862.

- ^ "Six New Isotopes of the Superheavy Elements Discovered". Berkeley Lab News Center. 26 October 2010. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ Ninov, Viktor; et al. (1999). "Observation of Superheavy Nuclei Produced in the Reaction of 86

Kr

with 208

Pb

". Physical Review Letters. 83 (6): 1104–1107. Bibcode:1999PhRvL..83.1104N. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.1104. - ^ "Results of Element 118 Experiment Retracted". Berkeley Lab Research News. 21 July 2001. Archived from the original on 29 January 2008. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ Cite warning:

<ref>tag with nameBloombergcannot be previewed because it is defined outside the current section or not defined in this article at all. - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Kratz, J. V. (2003). "Critical evaluation of the chemical properties of the transactinide elements (IUPAC Technical Report)" (PDF). Pure and Applied Chemistry. 75 (1): 103. doi:10.1351/pac200375010103. S2CID 5172663. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-26.

- ^ a b c d Cite warning:

<ref>tag with nameHairecannot be previewed because it is defined outside the current section or not defined in this article at all. - ^ Fricke, Burkhard (1975). "Superheavy elements: a prediction of their chemical and physical properties". Recent Impact of Physics on Inorganic Chemistry. Structure and Bonding. 21: 89–144. doi:10.1007/BFb0116498. ISBN 978-3-540-07109-9. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- ^ Eliav, E.; Kaldor, U.; Ishikawa, Y. (1995). "Ground State Electron Configuration of Rutherfordium: Role of Dynamic Correlation". Physical Review Letters. 74 (7): 1079–1082. Bibcode:1995PhRvL..74.1079E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.74.1079. PMID 10058929.

- ^ Mosyagin, N. S.; Tupitsyn, I. I.; Titov, A. V. (2010). "Precision Calculation of the Low-Lying Excited States of the Rf Atom". Radiochemistry. 52 (4): 394–398. doi:10.1134/S1066362210040120. S2CID 120721050.

- ^ Dzuba, V. A.; Safronova, M. S.; Safronova, U. I. (2014). "Atomic properties of superheavy elements No, Lr, and Rf". Physical Review A. 90 (1): 012504. arXiv:1406.0262. Bibcode:2014PhRvA..90a2504D. doi:10.1103/PhysRevA.90.012504. S2CID 74871880.

- ^ Cite warning:

<ref>tag with namehcpcannot be previewed because it is defined outside the current section or not defined in this article at all. - ^ Gyanchandani, Jyoti; Sikka, S. K. (10 May 2011). "Physical properties of the 6 d -series elements from density functional theory: Close similarity to lighter transition metals". Physical Review B. 83 (17): 172101. Bibcode:2011PhRvB..83q2101G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.83.172101.

- ^ Kratz; Lieser (2013). Nuclear and Radiochemistry: Fundamentals and Applications (3rd ed.). p. 631.

- ^ Gyanchandani, Jyoti; Sikka, S. K. (2011). "Structural Properties of Group IV B Element Rutherfordium by First Principles Theory" (Document). Bibcode:2011arXiv1106.3146G.

{cite document}: Cite document requires|publisher=(help); Unknown parameter|arxiv=ignored (help) - ^ Moody, Ken (2013-11-30). "Synthesis of Superheavy Elements". In Schädel, Matthias; Shaughnessy, Dawn (eds.). The Chemistry of Superheavy Elements (2nd ed.). Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 24–8. ISBN 9783642374661.

- ^ Oganessian, Yury Ts; Dmitriev, Sergey N. (2009). "Superheavy elements in D I Mendeleev's Periodic Table". Russian Chemical Reviews. 78 (12): 1077. Bibcode:2009RuCRv..78.1077O. doi:10.1070/RC2009v078n12ABEH004096. S2CID 250848732.

- ^ Türler, A.; Buklanov, G. V.; Eichler, B.; Gäggeler, H. W.; Grantz, M.; Hübener, S.; Jost, D. T.; Lebedev, V. Ya.; et al. (1998). "Evidence for relativistic effects in the chemistry of element 104". Journal of Alloys and Compounds. 271–273: 287. doi:10.1016/S0925-8388(98)00072-3.

- ^ Gäggeler, Heinz W. (2007-11-05). "Lecture Course Texas A&M: Gas Phase Chemistry of Superheavy Elements" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-02-20. Retrieved 2010-03-30.

- ^ Nagame, Y.; et al. (2005). "Chemical studies on rutherfordium (Rf) at JAERI" (PDF). Radiochimica Acta. 93 (9–10_2005): 519. doi:10.1524/ract.2005.93.9-10.519. S2CID 96299943. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-05-28.

- ^ Li, Z. J.; Toyoshima, A.; Asai, M.; et al. (2012). "Sulfate complexation of element 104, Rf, in H2SO4/HNO3 mixed solution". Radiochimica Acta. 100 (3): 157–164. doi:10.1524/ract.2012.1898. S2CID 100852185.

- ^ Kasamatsu, Yoshitaka; Toyomura, Keigo; Haba, Hiromitsu; et al. (2021). "Co-precipitation behaviour of single atoms of rutherfordium in basic solutions". Nature Chemistry. 13 (3): 226–230. doi:10.1038/s41557-020-00634-6. PMID 33589784. S2CID 231931604.

Bibliography

- Audi, G.; Kondev, F. G.; Wang, M.; et al. (2017). "The NUBASE2016 evaluation of nuclear properties". Chinese Physics C. 41 (3): 030001. Bibcode:2017ChPhC..41c0001A. doi:10.1088/1674-1137/41/3/030001.

- Beiser, A. (2003). Concepts of modern physics (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-244848-1. OCLC 48965418.

- Hoffman, D. C.; Ghiorso, A.; Seaborg, G. T. (2000). The Transuranium People: The Inside Story. World Scientific. ISBN 978-1-78-326244-1.

- Kragh, H. (2018). From Transuranic to Superheavy Elements: A Story of Dispute and Creation. Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-75813-8.

- Zagrebaev, V.; Karpov, A.; Greiner, W. (2013). "Future of superheavy element research: Which nuclei could be synthesized within the next few years?". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 420 (1): 012001. arXiv:1207.5700. Bibcode:2013JPhCS.420a2001Z. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/420/1/012001. ISSN 1742-6588. S2CID 55434734.

External links

Media related to Rutherfordium at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rutherfordium at Wikimedia Commons- Rutherfordium at The Periodic Table of Videos (University of Nottingham)

- WebElements.com – Rutherfordium