Tethys (mythology)

| Tethys | |

|---|---|

| Member of the Titans | |

| |

| Symbol | Winged brow |

| Genealogy | |

| Parents | Uranus and Gaia |

| Siblings |

|

| Consort | Oceanus |

| Offspring | Many river gods including:

Many Oceanids including: |

| Greek deities series |

|---|

| Water deities |

| Water nymphs |

In Greek mythology, Tethys (/ˈtiːθɪs, ˈtɛ-/; Ancient Greek: Τηθύς, romanized: Tēthýs) was a Titan daughter of Uranus and Gaia, a sister and wife of the Titan Oceanus, and the mother of the river gods and the Oceanids. Although Tethys had no active role in Greek mythology and no established cults,[2] she was depicted in mosaics decorating baths, pools, and triclinia in the Greek East, particularly in Antioch and its suburbs, either alone or with Oceanus.

Genealogy

Tethys was one of the Titan offspring of Uranus (Sky) and Gaia (Earth).[3] Hesiod lists her Titan siblings as Oceanus, Coeus, Crius, Hyperion, Iapetus, Theia, Rhea, Themis, Mnemosyne, Phoebe, and Cronus.[4] Tethys married her brother Oceanus, an enormous river encircling the world, and was by him the mother of numerous sons (the river gods) and numerous daughters (the Oceanids).[5]

According to Hesiod, there were three thousand (i.e. innumerable) river gods.[6] These included Achelous, the god of the Achelous River, the largest river in Greece, who gave his daughter in marriage to Alcmaeon[7] and was defeated by Heracles in a wrestling contest for the right to marry Deianira;[8] Alpheus, who fell in love with the nymph Arethusa and pursued her to Syracuse, where she was transformed into a spring by Artemis;[9] and Scamander who fought on the side of the Trojans during the Trojan War and, offended when Achilles polluted his waters with a large number of Trojan corpses, overflowed his banks nearly drowning Achilles.[10]

According to Hesiod, there were also three thousand Oceanids.[11] These included Metis, Zeus' first wife, whom Zeus impregnated with Athena and then swallowed;[12] Eurynome, Zeus' third wife, and mother of the Charites;[13] Doris, the wife of Nereus and mother of the Nereids;[14] Callirhoe, the wife of Chrysaor and mother of Geryon;[15] Clymene, the wife of Iapetus, and mother of Atlas, Menoetius, Prometheus, and Epimetheus;[16] Perseis, wife of Helios and mother of Circe and Aeetes;[17] Idyia, wife of Aeetes and mother of Medea;[18] and Styx, goddess of the river Styx, and the wife of Pallas and mother of Zelus, Nike, Kratos, and Bia.[19]

| Tethys' immediate family, according to Hesiod's Theogony [20] |

|---|

Primeval mother

Passages in book 14 of the Iliad, called the Deception of Zeus, suggest the possibility that Homer knew a tradition in which Oceanus and Tethys (rather than Uranus and Gaia, as in Hesiod) were the primeval parents of the gods.[26] Twice Homer has Hera describe the pair as "Oceanus, from whom the gods are sprung, and mother Tethys".[27] According to M. L. West, these lines suggests a myth in which Oceanus and Tethys are the "first parents of the whole race of gods."[28] However, as Timothy Gantz points out, "mother" could simply refer to the fact that Tethys was Hera's foster mother for a time, as Hera tells us in the lines immediately following, while the reference to Oceanus as the genesis of the gods "might be simply a formulaic epithet indicating the numberless rivers and springs descended from Okeanos" (compare with Iliad 21.195–197).[29] But, in a later Iliad passage, Hypnos also describes Oceanus as "genesis for all", which, according to Gantz, is hard to understand as meaning other than that, for Homer, Oceanus was the father of the Titans.[30]

Plato, in his Timaeus, provides a genealogy (probably Orphic) which perhaps reflected an attempt to reconcile this apparent divergence between Homer and Hesiod, in which Uranus and Gaia are the parents of Oceanus and Tethys, and Oceanus and Tethys are the parents of Cronus and Rhea and the other Titans, as well as Phorcys.[31] In his Cratylus, Plato quotes Orpheus as saying that Oceanus and Tethys were "the first to marry", possibly also reflecting an Orphic theogony in which Oceanus and Tethys—rather than Uranus and Gaia—were the primeval parents.[32] Plato's apparent inclusion of Phorkys as a Titan (being the brother of Cronus and Rhea), and the mythographer Apollodorus's inclusion of Dione, the mother of Aphrodite by Zeus, as a thirteenth Titan,[33] suggests an Orphic tradition in which Hesiod's twelve Titans were the offspring of Oceanus and Tethys, with Phorkys and Dione taking the place of Oceanus and Tethys.[34]

According to Epimenides, the first two beings, Night and Aer, produced Tartarus, who in turn produced two Titans (possibly Oceanus and Tethys) from whom came the world egg.[35]

Mythology

Tethys played no active part in Greek mythology. The only early story concerning Tethys is what Homer has Hera briefly relate in the Iliad’s Deception of Zeus passage.[37] There, Hera says that when Zeus was in the process of deposing Cronus, she was given by her mother Rhea to Tethys and Oceanus for safekeeping and that they "lovingly nursed and cherished me in their halls".[38] Hera relates this while dissembling that she is on her way to visit Oceanus and Tethys in the hopes of reconciling her foster parents, who are angry with each other and are no longer having sexual relations.

Originally Oceanus' consort, at a later time Tethys came to be identified with the sea, and in Hellenistic and Roman poetry Tethys' name came to be used as a poetic term for the sea.[39]

The only other story involving Tethys is an apparently late astral myth concerning the polar constellation Ursa Major (the Great Bear), which was thought to represent the catasterism of Callisto who was transformed into a bear and placed by Zeus among the stars. The myth explains why the constellation never sets below the horizon, saying that since Callisto had been Zeus's lover, she was forbidden by Tethys from "touching Ocean's deep" out of concern for her foster-child Hera, Zeus's jealous wife.[40]

Claudian wrote that Tethys nursed two of her nephlings in her breast, Helios and Selene, the children of her siblings Hyperion and Theia, during their infancy, when their light was weak and had not yet grown into their older, more luminous selves.[41]

In Ovid's Metamorphoses, Tethys turns Aesacus into a diving bird.[42]

Tethys was sometimes confused with another sea goddess, the sea-nymph Thetis, wife of Peleus and mother of Achilles.[43]

Tethys as Tiamat

M. L. West detects in the Iliad's Deception of Zeus passage an allusion to a possible archaic myth "according to which [Tethys] was the mother of the gods, long estranged from her husband," speculating that the estrangement might refer to a separation of "the upper and lower waters ... corresponding to that of heaven and earth," which parallels the story of "Apsū and Tiamat in the Babylonian cosmology, the male and female waters, which were originally united (En. El. I. 1 ff.)," but that, "By Hesiod's time the myth may have been almost forgotten and Tethys remembered only as the name of Oceanus' wife."[44] This possible correspondence between Oceanus and Tethys, and Apsū and Tiamat has been noticed by several authors, with Tethys' name possibly having been derived from that of Tiamat.[45]

Iconography

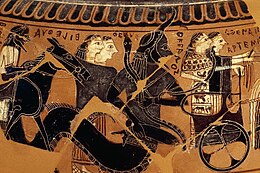

Representations of Tethys before the Roman period are rare.[47] Tethys appears, identified by inscription (ΘΕΘΥΣ), as part of an illustration of the wedding of Peleus and Thetis on the early sixth-century BC Attic black-figure "Erskine" dinos by Sophilos (British Museum 1971.111–1.1).[48] Accompanied by Eileithyia, the goddess of childbirth, Tethys follows close behind Oceanus at the end of a procession of gods invited to the wedding. Tethys is also conjectured to be represented in a similar illustration of the wedding of Peleus and Thetis depicted on the early sixth-century BC Attic black-figure François Vase (Florence 4209).[49] Tethys probably also appeared as one of the gods fighting the Giants in the Gigantomachy frieze of the second-century BC Pergamon Altar.[50] Only fragments of the figure remain: a part of a chiton below Oceanus' left arm and a hand clutching a large tree branch visible behind Oceanus' head.

During the second to fourth centuries AD, Tethys—sometimes with Oceanus, sometimes alone—became a relatively frequent feature of mosaics decorating baths, pools, and triclinia in the Greek East, particularly in Antioch and its suburbs.[52] Her identifying attributes are wings sprouting from her forehead, a rudder/oar, and a ketos, a creature from Greek mythology with the head of a dragon and the body of a snake.[53] The earliest of these mosaics, identified as Tethys, decorated a triclinium overlooking a pool, excavated from the House of the Calendar in Antioch, dated to shortly after AD 115 (Hatay Archaeology Museum 850).[54] Tethys, reclining on the left, with Oceanus reclining on the right, has long hair, a winged forehead, and is nude to the waist with draped legs. A ketos twines around her raised right arm. Other mosaics of Tethys with Oceanus include Hatay Archaeology Museum 1013 (from the House of Menander, Daphne),[55] Hatay Archaeology Museum 9095,[56] and Baltimore Museum of Art 1937.126 (from the House of the Boat of Psyches: triclinium).[57]

In other mosaics, Tethys appears without Oceanus. One of these is a fourth-century AD mosaic from a pool (probably a public bath) found at Antioch, now installed in Boston, Massachusetts at the Harvard Business School's Morgan Hall and formerly at Dumbarton Oaks, Washington, D.C. (Dumbarton Oaks 76.43).[58] Besides the Sophilos dinos, this is the only other representation of Tethys identified by inscription. Here Tethys, with a winged forehead, rises from the sea bare-shouldered, with long dark hair parted in the middle. A golden rudder rests against her right shoulder. Others include Hatay Archaeology Museum 9097,[59] Shahba Museum (in situ),[60] Baltimore Museum of Art 1937.118 (from the House of the Boat of Psyches: Room six),[61] and Memorial Art Gallery 42.2.[62]

Toward the end of the period represented by these mosaics, Tethys' iconography appears to merge with that of another sea goddess Thalassa, the Greek personification of the sea (thalassa being the Greek word for the sea).[63] Such a transformation would be consistent with the frequent use of Tethys' name as a poetic reference to the sea in Roman poetry (see above).

Modern use of the name

Tethys, a moon of the planet Saturn, and the prehistoric Tethys Ocean are named after this goddess.

Notes

- ^ LIMC 7630 (Tethys I (S) 16).

- ^ Burkert, p. 92.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 126 ff.; Caldwell, p. 35 line 126-128. Compare with Diodorus Siculus, 5.66.1–3, which says that the Titans (including Tethys) "were born, as certain writers of myths relate, of Uranus and Gê, but according to others, of one of the Curetes and Titaea, from whom as their mother they derive the name".

- ^ Apollodorus adds Dione to this list, while Diodorus Siculus leaves out Theia.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 337–370; Homer, Iliad 200–210, 14.300–304, 21.195–197; Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 137–138 (Sommerstein, pp. 458, 459), Seven Against Thebes 310–311 (Sommerstein, pp. 184, 185); Hyginus, Fabulae Preface (Smith and Trzaskoma, p. 95). For Tethys as mother of the river gods, see also: Diodorus Siculus, 4.69.1, 72.1. For Tethys as mother of the Oceanids, see also: Apollodorus, 1.2.2; Callimachus, Hymn 3.40–45 (Mair, pp. 62, 63); Apollonius of Rhodes, Argonautica, 242–244 (Seaton, pp. 210, 211). For a discussion of these offspring of Oceanus and Tethys, see Hard, pp. 40–43.

- ^ Hard, p. 40; Hesiod, Theogony 364–368, which says there are "as many" rivers as the "three thousand neat-ankled daughters of Ocean", and at 330–345, names 25 of these river gods: Nilus, Alpheus, Eridanos, Strymon, Maiandros, Istros, Phasis, Rhesus, Achelous, Nessos, Rhodius, Haliacmon, Heptaporus, Granicus, Aesepus, Simoeis, Peneus, Hermus, Caicus, Sangarius, Ladon, Parthenius, Evenus, Aldeskos, and Scamander. Compare with Acusilaus fr. 1 Fowler [= FGrHist 2 1 = Vorsokr. 9 B 21 = Macrobius, Saturnalia 5.18.9–10], which says that from Oceanus and Tethys, "spring three thousand rivers".

- ^ Apollodorus, 3.7.5.

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.8.1, 2.7.5.

- ^ Smith, s.v. "Alpheius".

- ^ Homer, Iliad 20.74, 21.211 ff..

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 346–366, which names 41 Oceanids: Peitho, Admete, Ianthe, Electra, Doris, Prymno, Urania, Hippo, Clymene, Rhodea, Callirhoe, Zeuxo, Clytie, Idyia, Pasithoe, Plexaura, Galaxaura, Dione, Melobosis, Thoe, Polydora, Cerceis, Plouto, Perseis, Ianeira, Acaste, Xanthe, Petraea, Menestho, Europa, Metis, Eurynome, Telesto, Chryseis, Asia, Calypso, Eudora, Tyche, Amphirho, Ocyrhoe, and Styx.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 886–900; Apollodorus, 1.3.6

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 907–909; Apollodorus, 1.3.1. Other sources give the Charites other parents, see Smith, s.v. "Charis".

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 240–264; Apollodorus, 1.2.7.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 286–288; Apollodorus, 2.5.10.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 351, however according to Apollodorus, 1.2.3, another Oceanid, Asia was their mother by Iapetus;

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 956–957; Apollodorus, 1.9.1.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 958–962; Apollodorus, 1.9.23.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 383–385; Apollodorus, 1.2.4.

- ^ Hesiod, Theogony 132–138, 337–411, 453–520, 901–906, 915–920; Caldwell, pp. 8–11, tables 11–14.

- ^ One of the Oceanid daughters of Oceanus and Tethys, at Hesiod, Theogony 351. However, according to Apollodorus, 1.2.3, a different Oceanid, Asia was the mother, by Iapetus, of Atlas, Menoetius, Prometheus, and Epimetheus.

- ^ Although usually, as here, the daughter of Hyperion and Theia, in the Homeric Hymn to Hermes (4), 99–100, Selene is instead made the daughter of Pallas the son of Megamedes.

- ^ According to Plato, Critias, 113d–114a, Atlas was the son of Poseidon and the mortal Cleito.

- ^ In Aeschylus, Prometheus Bound 18, 211, 873 (Sommerstein, pp. 444–445 n. 2, 446–447 n. 24, 538–539 n. 113) Prometheus is made to be the son of Themis.

- ^ Although, at Hesiod, Theogony 217, the Moirai are said to be the daughters of Nyx (Night).

- ^ Fowler 2013, pp. 8, 11; Hard, pp. 36–37, p. 40; West 1997, p. 147; Gantz, p. 11; Burkert 1995, pp. 91–92; West 1983, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Homer, Iliad 14.201, 302 [= 201].

- ^ West 1997, p. 147.

- ^ Gantz, p. 11.

- ^ Gantz, p. 11; Homer, Iliad 14.245.

- ^ Gantz, pp. 11–12; West 1983, pp. 117–118; Fowler 2013, p. 11; Plato, Timaeus 40d–e.

- ^ West 1983, pp. 118–120; Fowler 2013, p. 11; Plato, Cratylus 402b [= Orphic fr. 15 Kern].

- ^ Apollodorus, 1.1.3, 1.3.1.

- ^ Gantz, p. 743.

- ^ Fowler 2013, pp. 7–8.

- ^ LIMC 7683 (Tethys I (S) 10).

- ^ Gantz, p. 28: "For Tethys, there are no myths at all, save for Hera’s comment in the ‘’Iliad’’ that she was given by Rhea to Tethys to raise when Zeus was deposing Kronos"; Burkert, p. 92: “Tethys is in no way an active figure in Greek mythology”; West 1997, p. 147: "In early poetry she is merely an inactive mythological figure who lives with Oceanus and has borne his children."

- ^ Homer, Iliad 14.201–204.

- ^ West 1966, p. 204 136. Τῃθύν; West 1997, p. 147; Hard, p. 40; Matthews, p. 199. According to Matthews the "metonymy 'Tethys' = 'sea' seems to occur first in Hellenistic poetry", see for example Lycophron, Alexandria 1069 1069 (Mair, pp. 582–583)), becoming a frequent occurrence in Latin poetry, for example appearing nine times in Lucan.

- ^ Hard, p. 40; Hyginus, Fabulae 177; Astronomica 2.1; Ovid, Fasti 2.191–192 (Frazer, pp. 70, 71); Metamorphoses 2.508–530.

- ^ Claudian, Rape of Persephone Book II

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 11.784–795.

- ^ This happened "even in antiquity", according to Burkert, p. 92.

- ^ West 1966, p. 204; see also West 1983, pp. 120–121.

- ^ West 1997, pp. 147–148; Burkert, pp. 91–93. For a discussion of the possibility of oriental sources for the Illiad's Deception of Zeus passage, see Budelmann and Haubold, pp. 20–22.

- ^ LIMC 6487 (Tethys I (S) 1); Beazley Archive 350099; Avi 4748.

- ^ For a discussion of Tethy's iconography see Jentel, pp. 1193–1195.

- ^ LIMC 6487 (Tethys I (S) 1); Beazley Archive 350099; Avi 4748; Gantz, pp. 28, 229–230; Burkert, p. 202; Williams, pp. 27 fig. 34, 29, 31–32; Perseus: London 1971.11–1.1 (Vase); British Museum 1971,1101.1.

- ^ LIMC 1602 (Okeanos 3); Beazley Archive 300000; Perseus Florence 4209 (Vase). The identification as Tethys is accepted by Beazley, p. 27, and Gantz, p. 28, but found "unconvincing" by Carpenter p. 6. This vase is unremarked upon by Jentel, who says that the Sophilos dinos Tethys (LIMC Tethys I (S) 1) is the "seule representation de [Tethys] à l'époque archaique".

- ^ LIMC 617 (Tethys I (S) 2); Jentel, p. 1195; Queyrel, p. 67; Pollitt, p. 96.

- ^ LIMC 659 (Tethys I (S) 15).

- ^ For a discussion of this group of mosaics, see Jentel, 1194–1195, which lists 15 Roman period Tethys mosaics (Tethys I (S) 3–17), and Wages, pp. 119–128. Doro Levi identified the sea goddess in the Antioch mosaics as Thetis, however according to Wages, p. 126, "Neither the inscriptions nor the attributes in this group of mosaics support Doro Levi's identification". See also Kondoleon, p. 152 with p. 153 n. 2, which, in discussing one of these mosaics (Baltimore Museum of Art 1937.118, see below), says that "although the Baltimore goddess does not have any other attributes or label, she is convincingly identified as Tethys" saying further (in the note) that "Levi identified her as Thetis without much evidence, but Wages makes a good argument for identifying her as Tethys". Jentel identifies these mosaics as Tethys, while noting, p. 1195, that "Dès l'Antiquité et encore actuellement, certains auteurs ont confound [Tethys] avec la Néréeid Thetis."

- ^ Jentel, p. 1195; Wages, p. 125.

- ^ LIMC 735 (Tethys I (S) 5); Wages, pp. 120–124, fig. 2, p. 127; Hatay Archaeology Museum 850 Archived 2016-08-15 at the Wayback Machine; Campbell 1988, pp. 60–61 (identified as Thetis).

- ^ LIMC 659 (Tethys I (S) 15); Wages, p. 123 n. 24, fig. 8, p. 127; Hatay Archaeology Museum 1013 Archived 2016-08-15 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ LIMC 7630 (Tethys I (S) 16); Hatay Archaeology Museum 9095 Archived 2016-08-15 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ LIMC 661 (Tethys I (S) 17); Wages, p. 127; Baltimore Museum of Art 1937.126 Archived 2016-08-17 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ LIMC Tethys I (S) 7; Wages, 119–128; Jentel, p. 1195; Campbell 1988, p. 49.

- ^ 7916 (Tethys I (S) 3*); Wages, pp. 125, 128; Eraslan, p. 458; Hatay Archaeology Museum 9097.

- ^ LIMC 7683 (Tethys I (S) 10); Wages, p. 122, fig. 7, p. 125; Dunabin, p. 166.

- ^ LIMC 7627 (Tethys I (S) 11); Kondoleon, pp. 38–39; Wages, pp. 120–121, figs. 3, 4, p. 127; Baltimore Museum of Art 1937.118.

- ^ LIMC 7628 (Tethys I (S) 12*); Wages, p. 127; Memorial Art Gallery 42.2.

- ^ Wages, pp. 124–126; Jentel, p. 1195; Cahn, p. 1199; Campbell 1998, p. 20.

References

- Aeschylus(?), Prometheus Bound in Aeschylus, with an English translation by Herbert Weir Smyth, Ph. D. in two volumes. Vol 2. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press. 1926. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Aeschylus, Persians. Seven against Thebes. Suppliants. Prometheus Bound. Edited and translated by Alan H. Sommerstein. Loeb Classical Library No. 145. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, 2009. ISBN 978-0-674-99627-4. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Apollodorus, Apollodorus, The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George Frazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in 2 Volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1921. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Apollonius of Rhodes, Apollonius Rhodius: the Argonautica, translated by Robert Cooper Seaton, W. Heinemann, 1912. Internet Archive.

- Beazley, John Davidson, The Development of Attic Black-figure, Volume 24, University of California Press, 1951. ISBN 9780520055933.

- Budelmann, Felix and Johannes Haubold, "Reception and Tradition" in A Companion to Classical Receptions, edited by Lorna Hardwick and Christopher Stray, pp. 13–25. John Wiley & Sons, 2011. ISBN 9781444393774.

- Burkert, Walter The Orientalizing Revolution: Near Eastern Influence on Greek Culture in the Early archaic Age, Harvard University Press, 1992, pp. 91–93.

- Cahn, Herbert A., "Thalassa", in Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC) VIII.1 Artemis Verlag, Zürich and Munich, 1997. ISBN 3-7608-8758-9.

- Caldwell, Richard, Hesiod's Theogony, Focus Publishing/R. Pullins Company (June 1, 1987). ISBN 978-0-941051-00-2.

- Callimachus, Callimachus and Lycophron with an English translation by A. W. Mair; Aratus, with an English translation by G. R. Mair, London: W. Heinemann, New York: G. P. Putnam 1921. Internet Archive

- Campbell, Sheila D. (1988), The Mosaics of Antioch, PIMS. ISBN 9780888443649.

- Campbell, Sheila D. (1998), The Mosaics of Anemurium, PIMS. ISBN 9780888443748.

- Carpenter, Thomas H., Dionysian Imagery in Archaic Greek Art: Its Development in Black-Figure Vase Painting, Clarendon Press, 1986. ISBN 9780198132226.

- Diodorus Siculus, Diodorus Siculus: The Library of History. Translated by C. H. Oldfather. Twelve volumes. Loeb Classical Library. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press; London: William Heinemann, Ltd. 1989. Vol. 3. Books 4.59–8. ISBN 0674993756. Online version at Bill Thayer's Web Site

- Eraslan, Şehnaz. "Oceanus, Tethys and Thalssa Figures in the Light of Antioch and Zeugma Mosaics.", in: Journal of International Social Research 8.37 (2015), pp. 454–461.

- Fowler, R. L. (2000), Early Greek Mythography: Volume 1: Text and Introduction, Oxford University Press, 2000. ISBN 978-0198147404.

- Fowler, R. L. (2013), Early Greek Mythography: Volume 2: Commentary, Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0198147411.

- Gantz, Timothy, Early Greek Myth: A Guide to Literary and Artistic Sources, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, Two volumes: ISBN 978-0-8018-5360-9 (Vol. 1), ISBN 978-0-8018-5362-3 (Vol. 2).

- Hard, Robin, The Routledge Handbook of Greek Mythology: Based on H.J. Rose's "Handbook of Greek Mythology", Psychology Press, 2004, ISBN 9780415186360.

- Hesiod, Theogony, in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Homer, The Iliad with an English Translation by A.T. Murray, Ph.D. in two volumes. Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann, Ltd. 1924. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, Astronomica, in The Myths of Hyginus, edited and translated by Mary A. Grant, Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 1960.

- Hyginus, Gaius Julius, Fabulae in Apollodorus' Library and Hyginus' Fabulae: Two Handbooks of Greek Mythology, Translated, with Introductions by R. Scott Smith and Stephen M. Trzaskoma, Hackett Publishing Company, 2007. ISBN 978-0-87220-821-6.

- Homeric Hymn to Hermes (4), in The Homeric Hymns and Homerica with an English Translation by Hugh G. Evelyn-White, Cambridge, Massachusetts., Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1914. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Jentel, Marie-Odile, "Tethys I", in Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae (LIMC) VIII.1 Artemis Verlag, Zürich and Munich, 1997. ISBN 3-7608-8758-9.

- Kern, Otto. Orphicorum Fragmenta, Berlin, 1922. Internet Archive

- Kondoleon, Christine, Antioch: The Lost Ancient City, Princeton University Press, 2000. ISBN 9780691049328.

- Lycophron, Alexandra (or Cassandra) in Callimachus and Lycophron with an English translation by A. W. Mair; Aratus, with an English translation by G. R. Mair, London: W. Heinemann, New York: G. P. Putnam 1921. Internet Archive

- Macrobius, Saturnalia, Volume II: Books 3-5, edited and translated by Robert A. Kaster, Loeb Classical Library No. 511, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2011. Online version at Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-99649-6.

- Matthews, Monica, Caesar and the Storm: A Commentary on Lucan, De Bello Civili, Book 5, Lines 476–721, Peter Lang, 2008. ISBN 9783039107360.

- Most, G.W., Hesiod, Theogony, Works and Days, Testimonia, Edited and translated by Glenn W. Most, Loeb Classical Library No. 57, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2018. ISBN 978-0-674-99720-2. Online version at Harvard University Press.

- Ovid, Ovid's Fasti: With an English translation by Sir James George Frazer, London: W. Heinemann LTD; Cambridge, Massachusetts: : Harvard University Press, 1959. Internet Archive.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, Brookes More. Boston. Cornhill Publishing Co. 1922. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Plato, Cratylus in Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 12 translated by Harold N. Fowler, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1925. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Plato, Critias in Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 9 translated by W.R.M. Lamb. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1925. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Plato, Timaeus in Plato in Twelve Volumes, Vol. 9 translated by W.R.M. Lamb, Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press; London, William Heinemann Ltd. 1925. Online version at the Perseus Digital Library.

- Claudian, Rape of Persephone in Claudian: Volume II. Translated by Platnauer, Maurice. Loeb Classical Library Volume 136. Cambridge, MA. Harvard University Press. 1922.

- Pollitt, Jerome Jordan, Art in the Hellenistic Age, Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521276726.

- Queyrel, François, L'Autel de Pergame: Images et pouvoir en Grèce d'Asie, Paris: Éditions A. et J. Picard, 2005. ISBN 2-7084-0734-1.

- Smith, William; Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology, London (1873).

- Wages, Sara M., “A Note on the Dumbarton Oaks ‘Tethys Mosaic’” in: Dumbarton Oaks Papers 40 (1986), pp. 119–128.

- West, M. L. (1966), Hesiod: Theogony, Oxford University Press.

- West, M. L. (1983), The Orphic Poems, Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-814854-8.

- West, M. L. (1997), The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-815042-3.

- Williams, Dyfri, "Sophilos in the British Museum" in Greek Vases In The J. Paul Getty Museum, Getty Publications, 1983, pp. 9–34. ISBN 0-89236-058-5.