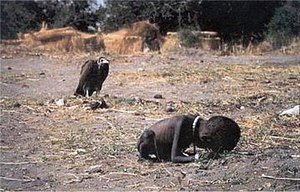

The Vulture and the Little Girl

The Vulture and the Little Girl, also known as The Struggling Girl, is a photograph by Kevin Carter which first appeared in The New York Times on 26 March 1993. It is a photograph of a frail famine-stricken boy, initially believed to be a girl,[1] who had collapsed in the foreground with a hooded vulture eyeing him from nearby. The child was reported to be attempting to reach a United Nations feeding centre about a half mile away in Ayod, Sudan (now South Sudan), in March 1993, and to have survived the incident. The picture won the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography award in 1994. Carter took his own life four months after winning the prize.

Background

The Hunger Triangle, a name relief organizations used in the 1990s for the area defined by the southern Sudan communities of Kongor, Ayod, and Waat, was dependent on UNESCO and other aid organizations to fight famine. Forty percent of the area's children under five years old were malnourished as of January 1993, and an estimated 10 to 13 adults died of starvation daily in Ayod alone.[2] To raise awareness of the situation, Operation Lifeline Sudan invited photojournalists and others, previously excluded from entering the country, to report on conditions. In March 1993, the government began granting visas to journalists for a 24-hour stay with severe restrictions on their travel within the country, including government supervision at all times.[3]

Silva and Carter in Sudan

Invitation by UN Operation Lifeline Sudan

In March 1993, Robert Hadley, a former photographer and at this time the information officer for the UN Operation Lifeline Sudan, invited João Silva and Kevin Carter to come to Sudan and report on the famine in the south of the country, travelling into southern Sudan with the rebels. Silva saw this as a chance to work more as a war photographer in the future. He started the arrangements and secured assignments for the expenses of the travel. Silva told Carter about the offer and Carter was also interested in going. According to fellow war photographer Greg Marinovich, Carter saw the trip as an opportunity to fix some problems "he felt trapped in". To take photos in Sudan was an opportunity for a better career as freelancer, and Carter was apparently "on a high, motivated and enthusiastic about the trip".[4] To pay for the travel, Carter secured some money from the Associated Press and others.[5]

Waiting in Nairobi

Silva and Carter stopped in Nairobi on their way to Sudan. The new fighting in Sudan forced them to wait there for an unspecified period of time.[clarification needed] Carter flew with the UN for one day to Juba in south Sudan to take photos of a barge, with food aid for the region, but soon the situation changed again. The UN received permission from a rebel group to fly food aid to Ayod. Rob Hadley was flying in on a UN light plane and invited Silva and Carter to fly with him to Ayod.[6]

In Ayod

The next day, their light aircraft touched down in the tiny hamlet of Ayod with the cargo aircraft landing shortly afterwards. The residents of the hamlet had been looked after by the UN aid station for some time. Greg Marinovich and João Silva described that in the book The Bang-Bang Club, Chapter 10 "Flies and Hungry People".[7] Marinovich wrote that the villagers were already waiting next to the runway to get the food as quickly as possible: "Mothers who had joined the throng waiting for food left their children on the sandy ground nearby."[8] Silva and Carter separated to take pictures of both children and adults, both the living and dead, all victims of the catastrophic famine that had arisen through the war. Carter went several times to Silva to tell him about the shocking situation he had just photographed. Witnessing the famine affected him emotionally. Silva was searching for rebel soldiers who could take him to someone in authority and when he found some soldiers Carter joined him. The soldiers did not speak English, but one was interested in Carter's watch. Carter gave him his cheap wristwatch as a gift.[9] The soldiers became their bodyguards and followed them for their protection.[10][11]

To stay a week with the rebels they needed the permission of a rebel commander. Their plane was due to depart in an hour and without the permission to stay, they would be forced to fly out. Again they separated and Silva went to the clinic complex to ask for the rebel commander and he was told the commander was in Kongor, South Sudan. This was good news for Silva, as "their little UN plane was heading there next". He left the clinic and went back to the runway, taking pictures of children and adults on his way. He came across a child lying on his face in the hot sun and took a picture.[12]

Carter saw Silva on the runway and told him, "You won't believe what I've just shot! … I was shooting this kid on her knees, and then changed my angle, and suddenly there was this vulture right behind her! … And I just kept shooting – shot lots of film!"[12] Silva asked him where he shot the picture and was looking around to take a photo as well. Carter pointed to a place 50 m (160 ft) away. Then Carter told him that he had chased the vulture away. He told Silva he was shocked by the situation he had just photographed, saying, "I see all this, and all I can think of is Megan", his young daughter. A few minutes later they left Ayod for Kongor.[13]

In 2011, the child's father revealed the child was actually a boy, Kong Nyong, and had been taken care of by the UN food aid station. Nyong had died in about 2007, of "fevers", according to his family.[1]

Publication and public reaction

In March 1993, The New York Times was seeking an image to illustrate a story by Donatella Lorch about the Sudan famine. Nancy Buirski, the newspaper's picture editor on the foreign desk, called Marinovich, who told her about "an image of a vulture stalking a starving child who had collapsed in the sand." Carter's photo was published in the 26 March 1993 edition.[14] The caption read: "A little girl, weakened from hunger, collapsed recently along the trail to a feeding center in Ayod. Nearby, a vulture waited."[3]

This first publication in The New York Times "caused a sensation", Marinovich wrote, adding, "It was being used in posters for raising funds for aid organisations. Papers and magazines around the world had published it, and the immediate public reaction was to send money to any humanitarian organisation that had an operation in Sudan."[15]

Claiming responsible ethical behaviour of photographers, publishers and the viewers of such photographs of shocking scenes, cultural writer Susan Sontag wrote in her essay Regarding the Pain of Others (2003):[16] "There is shame as well as shock in looking at the close-up of a real horror. Perhaps the only people with the right to look at images of suffering of this extreme order are those who could do something to alleviate it … or those who could learn from it. The rest of us are voyeurs, whether or not we mean to be."[17]

Special editorial

Due to the public reaction and questions about the child's condition, The New York Times published a special editorial in its 30 March 1993 edition, which said in part, "A picture last Friday with an article about the Sudan showed a little Sudanese girl who had collapsed from hunger on the trail to a feeding center in Ayod. A vulture lurked behind her. Many readers have asked about the fate of the girl. The photographer reports that she recovered enough to resume her trek after the vulture was chased away. It is not known whether she reached the center."[18]

Awards

- Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography (1994)[19][20]

- Picture of the Year by The American Magazine[21]

Aftermath

Kevin Carter

Four months after being awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography, Carter died by suicide via carbon monoxide poisoning on 27 July 1994 at age 33.[22][23] Desmond Tutu, Archbishop Emeritus of Cape Town, South Africa, wrote of Carter, "And we know a little about the cost of being traumatized that drove some to suicide, that, yes, these people were human beings operating under the most demanding of conditions."[24]

See also

References

Footnotes

- ^ a b Rojas, Alberto (21 February 2011). "Kong Nyong, el niño que sobrevivió al buitre" [Kong Nyong, The Boy Who Survived the Vulture]. El Mundo (in Spanish). Archived from the original on 30 June 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2017.

- ^ Rone, Jemera (1993). "Civilisation Devastation: Abuses by All Parties in the War in Southern Sudan". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ a b Lorch, Donatella (26 March 1993). "Sudan Is Described as Trying to Placate the West". The New York Times. Retrieved 28 November 2017.

- ^ Marinovich & Silva 2000, pp. 109–110.

- ^ Marinovich & Silva 2000, p. 110.

- ^ Marinovich & Silva 2000, p. 114.

- ^ Marinovich & Silva 2000, pp. 110–121.

- ^ Marinovich & Silva 2000, p. 115.

- ^ Marinovich & Silva 2000, p. 116.

- ^ Marinovich & Silva 2000, pp. 152–153.

- ^ "Carter and Soldiers". www.vimeo.com.

- ^ a b Marinovich & Silva 2000, p. 117.

- ^ Marinovich & Silva 2000, p. 118.

- ^ Marinovich & Silva 2000, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Marinovich & Silva 2000, p. 151.

- ^ Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others. New York: Picador/Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2003

- ^ O'Hagan, Sean (8 March 2010). "Viewer or Voyeur? The Morality of Reportage Photography". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 5 April 2021.

- ^ "Editors' Note". The New York Times. 30 March 1993. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ "The 1994 Pulitzer Prize Winner in Feature Photography". www.pulitzer.org. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ Macleod, Scott (24 June 2001). "The Life and Death of Kevin Carter". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved 31 December 2018.

- ^ McCabe, Eamonn (30 July 2014). "From the Archive, 30 July 1994: Photojournalist Kevin Carter Dies". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 30 July 2014. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- ^ Keller, Bill (29 July 1994). "Kevin Carter, a Pulitzer Winner for Sudan Photo, Is Dead at 33". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 September 2016.

- ^ Carlin, John (31 July 1994). "Obituary: Kevin Carter". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 17 January 2018. Retrieved 3 December 2017.

- ^ Tutu 2000, p. xi.

Bibliography

- Marinovich, Greg; Silva, João (2000). The Bang-Bang Club: Snapshots from a Hidden War. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-04413-9.

- Tutu, Desmond (2000). Foreword. The Bang-Bang Club: Snapshots from a Hidden War. By Marinovich, Greg; Silva, João. New York: Basic Books. pp. ix–xi. ISBN 978-0-465-04413-9.