Tropical Rainforest

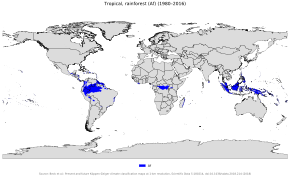

Tropical rainforests are dense and warm rainforests with high rainfall typically found between 10° north and south of the Equator. They are a subset of the tropical forest biome that occurs roughly within the 28° latitudes (in the torrid zone between the Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn). Tropical rainforests are a type of tropical moist broadleaf forest, that includes the more extensive seasonal tropical forests.[3] True rainforests usually occur in tropical rainforest climates where no dry season occurs; all months have an average precipitation of at least 60 mm (2.4 in). Seasonal tropical forests with tropical monsoon or savanna climates are sometimes included in the broader definition.

Tropical rainforests ecosystems are distinguished by their consistent, high temperatures, exceeding 18 °C (64 °F) monthly, and substantial annual rainfall. The abundant rainfall results in nutrient-poor, leached soils, which profoundly affect the flora and fauna adapted to these conditions. These rainforests are renowned for their significant biodiversity. They are home to 40–75% of all species globally, including half of the world's animal and plant species, and two-thirds of all flowering plant species. Their dense insect population and variety of trees and higher plants are notable. Described as the "world's largest pharmacy", over a quarter of natural medicines have been discovered in them. However, tropical rainforests are threatened by human activities, such as logging and agricultural expansion, leading to habitat fragmentation and loss.

The structure of a tropical rainforest is stratified into layers, each hosting unique ecosystems. These include the emergent layer with towering trees, the densely populated canopy layer, the understory layer rich in wildlife, and the forest floor, which is sparse due to low light penetration. The soil is characteristically nutrient-poor and acidic. Tropical rainforests have a long history of ecological succession, influenced by natural events and human activities. They are crucial for global ecological functions, including carbon sequestration and climate regulation. Many indigenous peoples around the world have inhabited rainforests for millennia, relying on them for sustenance and shelter, but face challenges from modern economic activities.

Conservation efforts are diverse, focusing on both preservation and sustainable management. International policies, such as the Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD and REDD+) programs, aim to curb deforestation and forest degradation. Despite these efforts, tropical rainforests continue to face significant threats from deforestation and climate change, highlighting the ongoing challenge of balancing conservation with human development needs.

Overview

Tropical rainforests are hot and wet. Mean monthly temperatures exceed 18 °C (64 °F) during all months of the year.[4] Average annual rainfall is no less than 1,680 mm (66 in) and can exceed 10 m (390 in) although it typically lies between 1,750 mm (69 in) and 3,000 mm (120 in).[5] This high level of precipitation often results in poor soils due to leaching of soluble nutrients in the ground.

Tropical rainforests exhibit high levels of biodiversity. Around 40% to 75% of all biotic species are indigenous to the rainforests.[6] Rainforests are home to half of all the living animal and plant species on the planet.[7] Two-thirds of all flowering plants can be found in rainforests.[5] A single hectare of rainforest may contain 42,000 different species of insect, up to 807 trees of 313 species and 1,500 species of higher plants.[5] Tropical rainforests have been called the "world's largest pharmacy", because over one quarter of natural medicines have been discovered within them.[8][9] It is likely that there may be many millions of species of plants, insects and microorganisms still undiscovered in tropical rainforests.

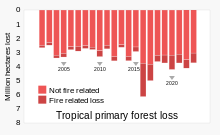

Tropical rainforests are among the most threatened ecosystems globally due to large-scale fragmentation as a result of human activity. Habitat fragmentation caused by geological processes such as volcanism and climate change occurred in the past, and have been identified as important drivers of speciation.[10] However, fast human driven habitat destruction is suspected to be one of the major causes of species extinction. Tropical rain forests have been subjected to heavy logging and agricultural clearance throughout the 20th century, and the area covered by rainforests around the world is rapidly shrinking.[11][12]

History

Tropical rainforests have existed on earth for hundreds of millions of years. Most tropical rainforests today are on fragments of the Mesozoic era supercontinent of Gondwana.[13] The separation of the landmass resulted in a great loss of amphibian diversity while at the same time the drier climate spurred the diversification of reptiles.[10] The division left tropical rainforests located in five major regions of the world: tropical America, Africa, Southeast Asia, Madagascar, and New Guinea, with smaller outliers in Australia.[13] However, the specifics of the origin of rainforests remain uncertain due to an incomplete fossil record.

Other types of tropical forest

Several biomes may appear similar-to, or merge via ecotones with, tropical rainforest:

- Moist seasonal tropical forest

Moist seasonal tropical forests receive high overall rainfall with a warm summer wet season and a cooler winter dry season. These forests usually fall under tropical monsoon or tropical savanna climates. Some trees in these forests drop some or all of their leaves during the winter dry season, thus they are sometimes called "tropical mixed forest". They are found in parts of South America, in Central America and around the Caribbean, in coastal West Africa, parts of the Indian subcontinent, and across much of Indochina.

- Montane rainforests

These are found in cooler-climate mountainous areas, becoming known as cloud forests at higher elevations. Depending on latitude, the lower limit of montane rainforests on large mountains is generally between 1500 and 2500 m while the upper limit is usually from 2400 to 3300 m.[14]

- Flooded rainforests

Tropical freshwater swamp forests, or "flooded forests", are found in Amazon basin (the Várzea) and elsewhere.

Forest structure

Rainforests are divided into different strata, or layers, with vegetation organized into a vertical pattern from the top of the soil to the canopy.[15] Each layer is a unique biotic community containing different plants and animals adapted for life in that particular strata. Only the emergent layer is unique to tropical rainforests, while the others are also found in temperate rainforests.[16]

Forest floor

The forest floor, the bottom-most layer, receives only 2% of the sunlight. Only plants adapted to low light can grow in this region. Away from riverbanks, swamps and clearings, where dense undergrowth is found, the forest floor is relatively clear of vegetation because of the low sunlight penetration. This more open quality permits the easy movement of larger animals such as: ungulates like the okapi (Okapia johnstoni), tapir (Tapirus sp.), Sumatran rhinoceros (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis), and apes like the western lowland gorilla (Gorilla gorilla), as well as many species of reptiles, amphibians, and insects. The forest floor also contains decaying plant and animal matter, which disappears quickly, because the warm, humid conditions promote rapid decay. Many forms of fungi growing here help decay the animal and plant waste.

Understory layer

The understory layer lies between the canopy and the forest floor. The understory is home to a number of birds, small mammals, insects, reptiles, and predators. Examples include leopard (Panthera pardus), poison dart frogs (Dendrobates sp.), ring-tailed coati (Nasua nasua), boa constrictor (Boa constrictor), and many species of Coleoptera.[5] The vegetation at this layer generally consists of shade-tolerant shrubs, herbs, small trees, and large woody vines which climb into the trees to capture sunlight. Only about 5% of sunlight breaches the canopy to arrive at the understory causing true understory plants to seldom grow to 3 m (10 feet). As an adaptation to these low light levels, understory plants have often evolved much larger leaves. Many seedlings that will grow to the canopy level are in the understory.

Canopy layer

The canopy is the primary layer of the forest, forming a roof over the two remaining layers. It contains the majority of the largest trees, typically 30–45 m in height. Tall, broad-leaved evergreen trees are the dominant plants. The densest areas of biodiversity are found in the forest canopy, as it often supports a rich flora of epiphytes, including orchids, bromeliads, mosses and lichens. These epiphytic plants attach to trunks and branches and obtain water and minerals from rain and debris that collects on the supporting plants. The fauna is similar to that found in the emergent layer, but more diverse. It is suggested that the total arthropod species richness of the tropical canopy might be as high as 20 million.[17] Other species inhabiting this layer include many avian species such as the yellow-casqued wattled hornbill (Ceratogymna elata), collared sunbird (Anthreptes collaris), grey parrot (Psitacus erithacus), keel-billed toucan (Ramphastos sulfuratus), scarlet macaw (Ara macao) as well as other animals like the spider monkey (Ateles sp.), African giant swallowtail (Papilio antimachus), three-toed sloth (Bradypus tridactylus), kinkajou (Potos flavus), and tamandua (Tamandua tetradactyla).[5]

Emergent layer

The emergent layer contains a small number of very large trees, called emergents, which grow above the general canopy, reaching heights of 45–55 m, although on occasion a few species will grow to 70–80 m tall.[15][18] Some examples of emergents include: Hydrochorea elegans, Dipteryx panamensis, Hieronyma alchorneoides, Hymenolobium mesoamericanum, Lecythis ampla and Terminalia oblonga.[19] These trees need to be able to withstand the hot temperatures and strong winds that occur above the canopy in some areas. Several unique faunal species inhabit this layer such as the crowned eagle (Stephanoaetus coronatus), the king colobus (Colobus polykomos), and the large flying fox (Pteropus vampyrus).[5]

However, stratification is not always clear. Rainforests are dynamic and many changes affect the structure of the forest. Emergent or canopy trees collapse, for example, causing gaps to form. Openings in the forest canopy are widely recognized as important for the establishment and growth of rainforest trees. It is estimated that perhaps 75% of the tree species at La Selva Biological Station, Costa Rica are dependent on canopy opening for seed germination or for growth beyond sapling size, for example.[20]

Ecology

Climates

Tropical rainforests are located around and near the equator, therefore having what is called an equatorial climate characterized by three major climatic parameters: temperature, rainfall, and dry season intensity.[21] Other parameters that affect tropical rainforests are carbon dioxide concentrations, solar radiation, and nitrogen availability. In general, climatic patterns consist of warm temperatures and high annual rainfall. However, the abundance of rainfall changes throughout the year creating distinct moist and dry seasons. Tropical forests are classified by the amount of rainfall received each year, which has allowed ecologists to define differences in these forests that look so similar in structure. According to Holdridge's classification of tropical ecosystems, true tropical rainforests have an annual rainfall greater than 2 m and annual temperature greater than 24 degrees Celsius, with a potential evapotranspiration ratio (PET) value of <0.25. However, most lowland tropical forests can be classified as tropical moist or wet forests, which differ in regards to rainfall. Tropical forest ecology- dynamics, composition, and function- are sensitive to changes in climate especially changes in rainfall.[21]

Soils

Soil types

Soil types are highly variable in the tropics and are the result of a combination of several variables such as climate, vegetation, topographic position, parent material, and soil age.[22] Most tropical soils are characterized by significant leaching and poor nutrients, however there are some areas that contain fertile soils. Soils throughout the tropical rainforests fall into two classifications which include the ultisols and oxisols. Ultisols are known as well weathered, acidic red clay soils, deficient in major nutrients such as calcium and potassium. Similarly, oxisols are acidic, old, typically reddish, highly weathered and leached, however are well drained compared to ultisols. The clay content of ultisols is high, making it difficult for water to penetrate and flow through. The reddish color of both soils is the result of heavy heat and moisture forming oxides of iron and aluminium, which are insoluble in water and not taken up readily by plants.

Soil chemical and physical characteristics are strongly related to above ground productivity and forest structure and dynamics. The physical properties of soil control the tree turnover rates whereas chemical properties such as available nitrogen and phosphorus control forest growth rates.[23] The soils of the eastern and central Amazon as well as the Southeast Asian Rainforest are old and mineral poor whereas the soils of the western Amazon (Ecuador and Peru) and volcanic areas of Costa Rica are young and mineral rich. Primary productivity or wood production is highest in western Amazon and lowest in eastern Amazon which contains heavily weathered soils classified as oxisols.[22] Additionally, Amazonian soils are greatly weathered, making them devoid of minerals like phosphorus, potassium, calcium, and magnesium, which come from rock sources. However, not all tropical rainforests occur on nutrient poor soils, but on nutrient rich floodplains and volcanic soils located in the Andean foothills, and volcanic areas of Southeast Asia, Africa, and Central America.[24]

Oxisols, infertile, deeply weathered and severely leached, have developed on the ancient Gondwanan shields. Rapid bacterial decay prevents the accumulation of humus. The concentration of iron and aluminium oxides by the laterization process gives the oxisols a bright red color and sometimes produces minable deposits (e.g., bauxite). On younger substrates, especially of volcanic origin, tropical soils may be quite fertile.

Nutrient recycling

This high rate of decomposition is the result of phosphorus levels in the soils, precipitation, high temperatures and the extensive microorganism communities.[25] In addition to the bacteria and other microorganisms, there are an abundance of other decomposers such as fungi and termites that aid in the process as well. Nutrient recycling is important because below ground resource availability controls the above ground biomass and community structure of tropical rainforests. These soils are typically phosphorus limited, which inhibits net primary productivity or the uptake of carbon.[22] The soil contains microbial organisms such as bacteria, which break down leaf litter and other organic matter into inorganic forms of carbon usable by plants through a process called decomposition. During the decomposition process the microbial community is respiring, taking up oxygen and releasing carbon dioxide. The decomposition rate can be evaluated by measuring the uptake of oxygen.[25] High temperatures and precipitation increase decomposition rate, which allows plant litter to rapidly decay in tropical regions, releasing nutrients that are immediately taken up by plants through surface or ground waters. The seasonal patterns in respiration are controlled by leaf litter fall and precipitation, the driving force moving the decomposable carbon from the litter to the soil. Respiration rates are highest early in the wet season because the recent dry season results in a large percentage of leaf litter and thus a higher percentage of organic matter being leached into the soil.[25]

Buttress roots

A common feature of many tropical rainforests is the distinct buttress roots of trees. Instead of penetrating to deeper soil layers, buttress roots create a widespread root network at the surface for more efficient uptake of nutrients in a very nutrient poor and competitive environment. Most of the nutrients within the soil of a tropical rainforest occur near the surface because of the rapid turnover time and decomposition of organisms and leaves.[26] Because of this, the buttress roots occur at the surface so the trees can maximize uptake and actively compete with the rapid uptake of other trees. These roots also aid in water uptake and storage, increase surface area for gas exchange, and collect leaf litter for added nutrition.[26] Additionally, these roots reduce soil erosion and maximize nutrient acquisition during heavy rains by diverting nutrient rich water flowing down the trunk into several smaller flows while also acting as a barrier to ground flow. Also, the large surface areas these roots create provide support and stability to rainforests trees, which commonly grow to significant heights. This added stability allows these trees to withstand the impacts of severe storms, thus reducing the occurrence of fallen trees.[26]

Forest succession

Succession is an ecological process that changes the biotic community structure over time towards a more stable, diverse community structure after an initial disturbance to the community. The initial disturbance is often a natural phenomenon or human caused event. Natural disturbances include hurricanes, volcanic eruptions, river movements or an event as small as a fallen tree that creates gaps in the forest. In tropical rainforests, these same natural disturbances have been well documented in the fossil record, and are credited with encouraging speciation and endemism.[10] Human land use practices have led to large-scale deforestation. In many tropical countries such as Costa Rica these deforested lands have been abandoned and forests have been allowed to regenerate through ecological succession. These regenerating young successional forests are called secondary forests or second-growth forests.

Biodiversity and speciation

Tropical rainforests exhibit a vast diversity in plant and animal species. The root for this remarkable speciation has been a query of scientists and ecologists for years. A number of theories have been developed for why and how the tropics can be so diverse.

Interspecific competition

Interspecific competition results from a high density of species with similar niches in the tropics and limited resources available. Species which "lose" the competition may either become extinct or find a new niche. Direct competition will often lead to one species dominating another by some advantage, ultimately driving it to extinction. Niche partitioning is the other option for a species. This is the separation and rationing of necessary resources by utilizing different habitats, food sources, cover or general behavioral differences. A species with similar food items but different feeding times is an example of niche partitioning.[27]

Pleistocene refugia

The theory of Pleistocene refugia was developed by Jürgen Haffer in 1969 with his article Speciation of Amazonian Forest Birds. Haffer proposed the explanation for speciation was the product of rainforest patches being separated by stretches of non-forest vegetation during the last glacial period. He called these patches of rainforest areas refuges and within these patches allopatric speciation occurred. With the end of the glacial period and increase in atmospheric humidity, rainforest began to expand and the refuges reconnected.[28] This theory has been the subject of debate. Scientists are still skeptical of whether or not this theory is legitimate. Genetic evidence suggests speciation had occurred in certain taxa 1–2 million years ago, preceding the Pleistocene.[29]

Human dimensions

Habitation

Tropical rainforests have harboured human life for many millennia, with many Indigenous people in South and Central America, who belong to the Indigenous peoples of the Americas, the Congo Pygmies in Central Africa, and several tribes in Southeast Asia, like the Dayak people and the Penan people in Borneo.[30] Food resources within the forest are extremely dispersed due to the high biological diversity and what food does exist is largely restricted to the canopy and requires considerable energy to obtain. Some groups of hunter-gatherers have exploited rainforest on a seasonal basis but dwelt primarily in adjacent savanna and open forest environments where food is much more abundant. Other people described as rainforest dwellers are hunter-gatherers who subsist in large part by trading high value forest products such as hides, feathers, and honey with agricultural people living outside the forest.[31]

Indigenous peoples

Many indigenous peoples around the world live within rainforests as hunter-gatherers, or subsist as part-time small scale farmers supplemented in large part by trading high-value forest products such as hides, feathers, and honey with agricultural people living outside the forests.[30][31] Peoples have inhabited the rainforests for tens of thousands of years and have remained so elusive that only recently have some tribes been discovered.[30] These indigenous peoples are greatly threatened by loggers in search for old-growth tropical hardwoods like Ipe, Cumaru and Wenge, and by farmers who are looking to expand their land, for cattle(meat), and soybeans, which are used to feed cattle in Europe and China.[30][32][33][34] On 18 January 2007, FUNAI reported also that it had confirmed the presence of 67 different uncontacted tribes in Brazil, up from 40 in 2005. With this addition, Brazil has now overtaken the island of New Guinea as the country having the largest number of uncontacted tribes.[35] The province of Irian Jaya or West Papua in the island of New Guinea is home to an estimated 44 uncontacted tribal groups.[36]

The pygmy peoples are hunter-gatherer groups living in equatorial rainforests characterized by their short height (below one and a half meters, or 59 inches, on average). Amongst this group are the Efe, Aka, Twa, Baka, and Mbuti people of Central Africa.[37] However, the term pygmy is considered pejorative so many tribes prefer not to be labeled as such.[38]

Some notable indigenous peoples of the Americas, or Amerindians, include the Huaorani, Ya̧nomamö, and Kayapo people of the Amazon. The traditional agricultural system practiced by tribes in the Amazon is based on swidden cultivation (also known as slash-and-burn or shifting cultivation) and is considered a relatively benign disturbance.[39][40] In fact, when looking at the level of individual swidden plots a number of traditional farming practices are considered beneficial. For example, the use of shade trees and fallowing all help preserve soil organic matter, which is a critical factor in the maintenance of soil fertility in the deeply weathered and leached soils common in the Amazon.[41]

There is a diversity of forest people in Asia, including the Lumad peoples of the Philippines and the Penan and Dayak people of Borneo. The Dayaks are a particularly interesting group as they are noted for their traditional headhunting culture. Fresh human heads were required to perform certain rituals such as the Iban "kenyalang" and the Kenyah "mamat".[42] Pygmies who live in Southeast Asia are, amongst others, referred to as "Negrito".

Resources

Cultivated foods and spices

Yam, coffee, chocolate, banana, mango, papaya, macadamia, avocado, and sugarcane all originally came from tropical rainforest and are still mostly grown on plantations in regions that were formerly primary forest. In the mid-1980s and 1990s, 40 million tons of bananas were consumed worldwide each year, along with 13 million tons of mango. Central American coffee exports were worth US$3 billion in 1970. Much of the genetic variation used in evading the damage caused by new pests is still derived from resistant wild stock. Tropical forests have supplied 250 cultivated kinds of fruit, compared to only 20 for temperate forests. Forests in New Guinea alone contain 251 tree species with edible fruits, of which only 43 had been established as cultivated crops by 1985.[43]

Ecosystem services

In addition to extractive human uses, rain forests also have non-extractive uses that are frequently summarized as ecosystem services. Rain forests play an important role in maintaining biological diversity, sequestering and storing carbon, global climate regulation, disease control, and pollination.[44] Half of the rainfall in the Amazon area is produced by the forests. The moisture from the forests is important to the rainfall in Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina[45] Deforestation in the Amazon rainforest region was one of the main reason that cause the severe Drought of 2014–2015 in Brazil[46][47] For the last three decades, the amount of carbon absorbed by the world's intact tropical forests has fallen, according to a study published in 2020 in the journal Nature. In 2019 they took up a third less carbon than they did in the 1990s, due to higher temperatures, droughts and deforestation. The typical tropical forest may become a carbon source by the 2060s.[48]

Tourism

Despite the negative effects of tourism in the tropical rainforests, there are also several important positive effects.

- In recent years ecotourism in the tropics has increased. While rainforests are becoming increasingly rare, people are travelling to nations that still have this diverse habitat. Locals are benefiting from the additional income brought in by visitors, as well areas deemed interesting for visitors are often conserved. Ecotourism can be an incentive for conservation, especially when it triggers positive economic change.[49] Ecotourism can include a variety of activities including animal viewing, scenic jungle tours and even viewing cultural sights and native villages. If these practices are performed appropriately this can be beneficial for both locals and the present flora and fauna.

- An increase in tourism has increased economic support, allowing more revenue to go into the protection of the habitat. Tourism can contribute directly to the conservation of sensitive areas and habitat. Revenue from park-entrance fees and similar sources can be utilised specifically to pay for the protection and management of environmentally sensitive areas. Revenue from taxation and tourism provides an additional incentive for governments to contribute revenue to the protection of the forest.

- Tourism also has the potential to increase public appreciation of the environment and to spread awareness of environmental problems when it brings people into closer contact with the environment. Such increased awareness can induce more environmentally conscious behavior. Tourism has had a positive effect on wildlife preservation and protection efforts, notably in Africa but also in South America, Asia, Australia, and the South Pacific.[50]

Conservation

Threats

Deforestation

Mining and drilling

Deposits of precious metals (gold, silver, coltan) and fossil fuels (oil and natural gas) occur underneath rainforests globally. These resources are important to developing nations and their extraction is often given priority to encourage economic growth. Mining and drilling can require large amounts of land development, directly causing deforestation. In Ghana, a West African nation, deforestation from decades of mining activity left about 12% of the country's original rainforest intact.[52]

Conversion to agricultural land

With the invention of agriculture, humans were able to clear sections of rainforest to produce crops, converting it to open farmland. Such people, however, obtain their food primarily from farm plots cleared from the forest[31][53] and hunt and forage within the forest to supplement this. The issue arising is between the independent farmer providing for his family and the needs and wants of the globe as a whole. This issue has seen little improvement because no plan has been established for all parties to be aided.[54]

Agriculture on formerly forested land is not without difficulties. Rainforest soils are often thin and leached of many minerals, and the heavy rainfall can quickly leach nutrients from area cleared for cultivation. People such as the Yanomamo of the Amazon, utilize slash-and-burn agriculture to overcome these limitations and enable them to push deep into what were previously rainforest environments. However, these are not rainforest dwellers, rather they are dwellers in cleared farmland[31][53] that make forays into the rainforest. Up to 90% of the typical Yanamomo diet comes from farmed plants.[53]

Some action has been taken by suggesting fallow periods of the land allowing secondary forest to grow and replenish the soil.[55] Beneficial practices like soil restoration and conservation can benefit the small farmer and allow better production on smaller parcels of land.

Climate change

The tropics take a major role in reducing atmospheric carbon dioxide. The tropics (most notably the Amazon rainforest) are called carbon sinks.[citation needed] As major carbon reducers and carbon and soil methane storages, their destruction contributes to increasing global energy trapping, atmospheric gases.[citation needed] Climate change has been significantly contributed to by the destruction of the rainforests. A simulation was performed in which all rainforest in Africa were removed. The simulation showed an increase in atmospheric temperature by 2.5 to 5 degrees Celsius.[56]

Declining populations

Some species of fauna show a trend towards declining populations in rainforests, for example, reptiles that feed on amphibians and reptiles. This trend requires close monitoring.[57] The seasonality of rainforests affects the reproductive patterns of amphibians, and this in turn can directly affect the species of reptiles that feed on these groups,[58] particularly species with specialized feeding, since these are less likely to use alternative resources.[59]

Protection

Efforts to protect and conserve tropical rainforest habitats are diverse and widespread. Tropical rainforest conservation ranges from strict preservation of habitat to finding sustainable management techniques for people living in tropical rainforests. International policy has also introduced a market incentive program called Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation (REDD) for companies and governments to outset their carbon emissions through financial investments into rainforest conservation.[60]

See also

References

- ^ Why the Amazon Rainforest is So Rich in Species Archived 25 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine. Earthobservatory.nasa.gov (5 December 2005). Retrieved on 28 March 2013.

- ^ Why The Amazon Rainforest Is So Rich In Species. ScienceDaily.com (5 December 2005). Retrieved on 28 March 2013.

- ^ Olson, David M.; Dinerstein, Eric; Wikramanayake, Eric D.; Burgess, Neil D.; Powell, George V. N.; Underwood, Emma C.; d'Amico, Jennifer A.; Itoua, Illanga; et al. (2001). "Terrestrial Ecoregions of the World: A New Map of Life on Earth". BioScience. 51 (11): 933–938. doi:10.1641/0006-3568(2001)051[0933:TEOTWA]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ Woodward, Susan. Tropical broadleaf Evergreen Forest: The rainforest. Archived 25 February 2008 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 14 March 2009.

- ^ a b c d e f Newman, Arnold (2002). Tropical Rainforest: Our Most Valuable and Endangered Habitat With a Blueprint for Its Survival into the Third Millennium (2 ed.). Checkmark. ISBN 0816039739.

- ^ "Rainforests.net – Variables and Math". Archived from the original on 5 December 2008. Retrieved 4 January 2009.

- ^ The Regents of the University of Michigan. The Tropical Rain Forest. Retrieved on 14 March 2008.

- ^ Rainforests Archived 8 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Animalcorner.co.uk (1 January 2004). Retrieved on 28 March 2013.

- ^ The bite that heals. Ngm.nationalgeographic.com (25 February 2013). Retrieved on 24 June 2016.

- ^ a b c Sahney, S., Benton, M.J. & Falcon-Lang, H.J. (2010). "Rainforest collapse triggered Pennsylvanian tetrapod diversification in Euramerica". Geology. 38 (12): 1079–1082. Bibcode:2010Geo....38.1079S. doi:10.1130/G31182.1.

{cite journal}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Brazil: Deforestation rises sharply as farmers push into Amazon, The Guardian, 1 September 2008

- ^ China is black hole of Asia's deforestation, Asia News, 24 March 2008

- ^ a b Corlett, R. & Primack, R. (2006). "Tropical Rainforests and the Need for Cross-continental Comparisons". Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 21 (2): 104–110. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2005.12.002. PMID 16701482.

- ^ Bruijnzeel, L. A. & Veneklaas, E. J. (1998). "Climatic Conditions and Tropical Montane Forest Productivity: The Fog Has Not Lifted Yet". Ecology. 79 (1): 3. doi:10.1890/0012-9658(1998)079[0003:CCATMF]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ a b Bourgeron, Patrick S. (1983). "Spatial Aspects of Vegetation Structure". In Frank B. Golley (ed.). Tropical Rain Forest Ecosystems. Structure and Function. Ecosystems of the World (14A ed.). Elsevier Scientific. pp. 29–47. ISBN 0-444-41986-1.

- ^ Webb, Len (1 October 1959). "A Physiognomic Classification of Australian Rain Forests". Journal of Ecology. 47 (3). British Ecological Society : Journal of Ecology Vol. 47, No. 3, pp. 551–570: 551–570. Bibcode:1959JEcol..47..551W. doi:10.2307/2257290. JSTOR 2257290.

- ^ Erwin, T.L. (1982). "Tropical forests: Their richness in Coleoptera and other arthropod species" (PDF). The Coleopterists Bulletin. 36 (1): 74–75. JSTOR 4007977.

- ^ "Sabah". Eastern Native Tree Society. Retrieved 14 November 2007.

- ^ King, David A. & Clark, Deborah A. (2011). "Allometry of Emergent Tree Species from Saplings to Above-canopy Adults in a Costa Rican Rain Forest". Journal of Tropical Ecology. 27 (6): 573–79. doi:10.1017/S0266467411000319. S2CID 8799184.

- ^ Denslow, J S (1987). "Tropical Rainforest Gaps and Tree Species Diversity". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 18: 431. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.18.110187.002243.

- ^ a b Malhi, Yadvinder & Wright, James (2004). "Spatial patterns and recent trends in the climate of tropical rainforest regions". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 359 (1443): 311–329. doi:10.1098/rstb.2003.1433. PMC 1693325. PMID 15212087.

- ^ a b c Aragao, L. E. O. C. (2009). "Above- and below-ground net primary productivity across ten Amazonian forests on contrasting soils". Biogeosciences. 6 (12): 2759–2778. Bibcode:2009BGeo....6.2759A. doi:10.5194/bg-6-2759-2009. hdl:10871/11001.

- ^ Moreira, A.; Fageria, N. K.; Garcia y Garcia, A. (2011). "Soil Fertility, Mineral Nitrogen, and Microbial Biomass in Upland Soils of the Central Amazon under Different Plant Covers" (PDF). Communications in Soil Science and Plant Analysis. 42 (6): 694–705. Bibcode:2011CSSPA..42..694M. doi:10.1080/00103624.2011.550376. S2CID 73689568.

- ^ Environmental news and information. mongabay.com. Retrieved on 28 March 2013.

- ^ a b c Cleveland, Cory C. & Townsend, Alan R. (2006). "Nutrient additions to a tropical rain forest drive substantial soil carbon dioxide losses to the atmosphere". PNAS. 103 (27): 10316–10321. Bibcode:2006PNAS..10310316C. doi:10.1073/pnas.0600989103. PMC 1502455. PMID 16793925.

- ^ a b c Tang, Yong; Yang, Xiaofei; Cao, Min; Baskin, Carol C.; Baskin, Jerry M. (2010). "Buttress Trees Elevate Soil Heterogeneity and Regulate Seedling Diversity in a Tropical Rainforest" (PDF). Plant and Soil. 338 (1–2): 301–309. doi:10.1007/s11104-010-0546-4. S2CID 34892121.

- ^ Sahney, S., Benton, M.J. and Ferry, P.A. (2010). "Links between global taxonomic diversity, ecological diversity and the expansion of vertebrates on land". Biology Letters. 6 (4): 544–547. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.1024. PMC 2936204. PMID 20106856.

{cite journal}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Haffer, J. (1969). "Speciation in Amazonian Forest Birds". Science. 165 (131): 131–7. Bibcode:1969Sci...165..131H. doi:10.1126/science.165.3889.131. PMID 17834730.

- ^ Moritz, C.; Patton, J. L.; Schneider, C. J.; Smith, T. B. (2000). "DIVERSIFICATION OF RAINFOREST FAUNAS: An Integrated Molecular Approach". Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 31: 533. doi:10.1146/annurev.ecolsys.31.1.533.

- ^ a b c d Barton, Huw; Denham, Tim; Neumann, Katharina; Arroyo-Kalin, Manuel (2012). "Long-term perspectives on human occupation of tropical rainforests: An introductory overview". Quaternary International. 249: 1–3. Bibcode:2012QuInt.249....1B. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.07.044.

- ^ a b c d Bailey, R.C., Head, G., Jenike, M., Owen, B., Rechtman, R., Zechenter, E. (1989). "Hunting and gathering in tropical rainforest: is it possible". American Anthropologist. 91 (1): 59–82. doi:10.1525/aa.1989.91.1.02a00040.

{cite journal}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ 'They're killing us': world's most endangered tribe cries for help. The Guardian (22 April 2012). Retrieved on 24 June 2016.

- ^ Sibaja, Marco (6 June 2012) Brazil's Indigenous Awa Tribe At Risk. Huffington Post

- ^ González-Ruibal, Alfredo; Hernando, Almudena; Politis, Gustavo (2011). "Ontology of the self and material culture: Arrow-making among the Awá hunter–gatherers (Brazil)". Journal of Anthropological Archaeology. 30: 1. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2010.10.001. hdl:10261/137811.

- ^ Brazil sees traces of more isolated Amazon tribes. Reuters.com (17 January 2007). Retrieved on 28 March 2013.

- ^ BBC: First contact with isolated tribes? survivalinternational.org (25 January 2007)

- ^ "People of the Congo Rainforest". Mongabay.com. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

- ^ Forest peoples in the central African rain forest: focus on the pygmies. fao.org

- ^ Dufour, D. R. (1990). "Use of tropical rainforest by native Amazonians" (PDF). BioScience. 40 (9): 652–659. doi:10.2307/1311432. JSTOR 1311432. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 November 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2013.

- ^ Herrera, Rafael; Jordan, Carl F.; Medina, Ernesto & Klinge, Hans (1981). "How Human Activities Disturb the Nutrient Cycles of a Tropical Rainforest in Amazonia". Ambio. 10 (2/3, MAB: A Special Issue): 109–114. JSTOR 4312652.

- ^ Ewel, J J (1986). "Designing Agricultural Ecosystems for the Humid Tropics". Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 17: 245–271. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.17.110186.001333. JSTOR 2096996.

- ^ Jessup, T. C. & Vayda, A. P. (1988). "Dayaks and forests of interior Borneo" (PDF). Expedition. 30 (1): 5–17.

- ^ Myers, N. (1985). The primary source, W. W. Norton and Co., New York, pp. 189–193, ISBN 0-393-30262-8

- ^ Foley, Jonathan A.; Asner, Gregory P.; Costa, Marcos Heil; Coe, Michael T.; Defries, Ruth; Gibbs, Holly K.; Howard, Erica A.; Olson, Sarah; et al. (2007). "Amazonia revealed: forest degradation and loss of ecosystem goods and services in the Amazon Basin". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 5 (1): 25–32. doi:10.1890/1540-9295(2007)5[25:ARFDAL]2.0.CO;2.

- ^ E. Lovejoy, Thomas; Nobre, Carlos (21 February 2018). "Amazon Tipping Point". Science Advances. 4 (2): eaat2340. Bibcode:2018SciA....4.2340L. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aat2340. PMC 5821491. PMID 29492460.

- ^ Watts, Jonathan (28 November 2017). "The Amazon effect: how deforestation is starving São Paulo of water". The Guardian. Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ VERCHOT, LOUIS (29 January 2015). "The science is clear: Forest loss behind Brazil's drought". Center for International Forestry Research (CIFOR). Retrieved 8 November 2018.

- ^ Harvey, Fiona (4 March 2020). "Tropical forests losing their ability to absorb carbon, study finds". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 5 March 2020.

- ^ Stronza, A. & Gordillo, J. (2008). "Community views of ecotourism: Redefining benefits" (PDF). Annals of Tourism Research. 35 (2): 448. doi:10.1016/j.annals.2008.01.002.

- ^ Fotiou, S. (October 2001). Environmental Impacts of Tourism. Retrieved 30 November 2007, from Uneptie.org Archived 28 December 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Forest Pulse: The Latest on the World's Forests". WRI.org. World Resources Institute. June 2023. Archived from the original on 27 June 2023.

- ^ Ismi, A. (1 October 2003), Canadian mining companies set to destroy Ghana's forest reserves, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives Monitor, Ontario, Canada.

- ^ a b c Walker, Philip L.; Sugiyama, Larry and Chacon, Richard (1998) "Diet, Dental Health, and Cultural Change among Recently Contacted South American Indian Hunter-Horticulturalists", Ch. 17 in Human Dental Development, Morphology, and Pathology. University of Oregon Anthropological Papers, No. 54

- ^ Tomich, P. T., Noordwijk, V. M., Vosti, A. S., Witcover, J (1998). "Agricultural development with rainforest conservation: methods for seeking best bet alternatives to slash-and-burn, with applications to Brazil and Indonesia" (PDF). Agricultural Economics. 19 (1–2): 159–174. doi:10.1016/S0169-5150(98)00032-2.

{cite journal}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ De Jong, Wil; Freitas, Luis; Baluarte, Juan; Van De Kop, Petra; Salazar, Angel; Inga, Erminio; Melendez, Walter; Germaná, Camila (2001). "Secondary forest dynamics in the Amazon floodplain in Peru". Forest Ecology and Management. 150 (1–2): 135–146. Bibcode:2001ForEM.150..135D. doi:10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00687-3.

- ^ Semazzi, F. H., Song, Y (2001). "A GCM study of climate change induced by deforestation in Africa". Climate Research. 17: 169–182. Bibcode:2001ClRes..17..169S. doi:10.3354/cr017169.

{cite journal}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Barquero-González, J.P., Stice, T.L., Gómez, G., & Monge- Nájera, J. (2020). Are tropical reptiles really declining? A six-year survey of snakes in a tropical coastal rainforest: role of prey and environment. Revista de Biología Tropical, 68(1), 336–343.

- ^ Oliveira, M.E., & Martins, M. (2001). When and where to find a pitviper: activity patterns and habitat use of the lancehead, Bothrops atrox, in central Amazonia, Brazil. Herpetological Natural History, 8(2), 101-110.

- ^ Terborgh, J., & Winter, B. (1980). Some causes of extinction. Conservation Biology, 2, 119-133.

- ^ Varghese, Paul (August 2009). "An Overview of REDD, REDD Plus and REDD Readiness" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2010. Retrieved 23 November 2009.

External links

- Rainforest Action Network

- Rain Forest Info from Blue Planet Biomes

- Passport to Knowledge Rainforests

- Tropical Forests, Project Regeneration, 2021.