Uti possidetis

Uti possidetis is an expression that originated in Roman private law, where it was the name of a procedure about possession of land. Later, by a misleading analogy, it was transferred to international law, where it has had more than one meaning, all concerning sovereign right to territory.

In Rome, if two parties disputed possession of a house or parcel of land, the praetor preferred the one who was in actual occupation, unless he had got it from the other by force, stealth or as a temporary favour (nec vi, nec clam, nec precario). The contest was initiated by an interdict called uti possidetis. The winner was confirmed or restored in possession, and the loser was ordered not to displace him by force. However, the winner had not proved he was the real owner, only that, for the moment, he had a better right to possession than his opponent. Hence the rights of third parties were not prejudiced. The phrase uti possidetis was a conventional abbreviation of the praetorial edict dealing with such matters.

In the early modern era, some European states, when dealing with other European states, used the phrase to justify the acquisition of territory by occupation. There was no universally agreed rule and, for example, Portugal applied it more ambitiously than Spain. Despite that, there is no doubt that important polities, such as Brazil, were established on that interpretation. It was also a generally accepted rule about the interpretation of peace treaties. A peace treaty was presumed to give each party a permanent right to the territory it occupied at the conclusion of hostilities, unless the contrary was expressly stipulated. Whether this rule has survived in the international regime following the creation of the United Nations must be doubtful. This usage is sometimes called uti possidetis de facto.

In recent times, uti possidetis refers to a doctrine for drawing international boundaries. When colonial territories achieve independence, or when a polity breaks up (e.g., Yugoslavia), then, in default of a better rule, the old administrative boundaries between the new states ought to be followed. This doctrine, which has its critics, is sometimes called uti possidetis juris.

Roman law

Introduction

A displaced landowner had a theoretically simple way to recover his property: a traditional action called vindicatio. All he had to do was to prove he was the owner and the defendant was in possession. However, in reality proof of ownership could be exceedingly difficult[1] for lack of documentation since, during the formative period of Roman law, there was no system of written conveyancing and registration of land. In the Republican era most land transfers were verbal and did not even have to be witnessed.[2] Consequently, as time went by, there must have been many Roman estates whose owners could not prove they were.

Accordingly, in litigation about land each party tried to manoeuvre a situation where the burden of proof was cast on his opponent, and he merely had to defend.[3] To achieve this they went outside the traditional Roman actions and used a praetorial remedy.

Praetorial remedies

Already in the Roman republic the praetor was an official whose duties included the keeping of the peace. A praetor held office for a year, at the start of which it was customary for him to publish edicts; these announced the legal policies he intended to apply. Usually they were adopted with or without modification by his successors. With these edicts praetors could change the law, though they did it somewhat cautiously.[4]

An interdict was a praetorial order forbidding someone to do something. The one relevant for present purposes was the interdictum uti possidetis. It seems this interdict was available by about 169 B.C. because there is a joke about it in one of Terence's comedies, though we do not know the praetor's original wording.[5] Probably it originated as a means of protecting occupants of public lands, since these people could not sue as owners.[6] Later, however, it was adapted as a procedural device to assign disputants to the role of plaintiff and defendant, respectively.[7]

The interdict uti possidetis

According to the Roman jurist Gaius (Institutes, Fourth Commentary):

| Latin text[8] | English translation[9] (emphasis added) |

|---|---|

| § 148. Retinendae possessionis causa solet interdictum reddi, cum ab utraque parte de proprietate alicuius rei controuersia est, et ante quaeritur uter ex litigatoribus possidere et uter petere debeat; cuius rei gratia comparata sunt VTI POSSIDETIS et VTRVBI. | Interdicts for retaining possession are regularly granted when two parties are disputing about the ownership of a thing, and the question which has to be determined in the first place is which of the litigants shall be plaintiff and which defendant in the vindication*; it is for this purpose that the interdicta Uti possidetis and Utrubi have been established. |

| § 149. Et quidem VTI POSSIDETIS interdictum de fundi uel aedium possessione redditur, VTRVBI uero de rerum mobilium possessione. | The former interdict is granted in respect of the possession of land and houses, the latter in respect of the possession of movables. |

| § 150. Et siquidem de fundo uel aedibus interdicitur, eum potiorem esse praetor iubet, qui eo tempore quo interdictum redditur nec ui nec clam nec precario ab aduersario possideat; si uero de re mobili, eum potiorem esse iubet, qui maiore parte eius anni nec ui nec clam nec precario ab aduersario possederit; idque satis ipsis uerbis interdictorum significatur. | When the interdict relates to land or houses, the praetor prefers the party who at the issuing of the interdict is in actual possession, such possession not having been obtained from the opposing party either by violence or clandestinely, or by his permission. When the interdict relates to a movable, he prefers the party who in respect of the adversary has possessed without violence, clandestinity, or permission, during the greater part of that year. The terms of the interdicts sufficiently show this distinction. |

*The vindication was the name of the traditional action for claiming ownership of land, as already explained.

A person could establish possession by occupying the property himself, or through another e.g. his inquilinus (house tenant) or colonus (agricultural tenant).[10]

The three exceptions: nec vi nec clam nec precario

That the praetor would confirm the party in possession was only a default rule, since there were three exceptions:

- Vi (force). If the possessing party had got it from the other[11] by force he was not entitled to the benefit of the interdict. Otherwise it would reward the getting of land by violence.

- Clam (stealth). Likewise if his possession had been obtained furtively; and for a similar reason.

- Precario. A precario was a person who was in possession only by favour, and could be told to leave at any time. (Hence the English word precarious.)

If any of those exceptions applied his possession was flawed (this was called possessio vitiosa)[12] and did not count.

Third parties

If he had got his possession from a third party, though, it did not matter that he had done it illegitimately, i.e. it was of no present relevance. This is made explicitly clear by Justinian's Institutes, IV, XV §5:

He came off victorious who was in possession at the time of the interdict, provided he had not acquired possession as against his adversary by force, or secretly, or at will, although he had expelled some other person by force, or had secretly deprived him of the possession, or had asked some one [else] to allow him to possess at will.[13] [Emphasis added]

It was up to the third party to initiate legal proceedings about that, if he wanted to; he was not shut out.[14]

This was significant when early modern European powers sought to apply the uti possidetis concept to their colonial acquisitions (see below). Thus, that they had vanquished the indigenous inhabitants by force was of no present consequence if a dispute was between rival Europeans.[15]

Procedure

On the first appearance in court the praetor, whose time was valuable, did not try to investigate the facts. He simply pronounced the interdict impartially against both parties. (Hence it was called a "double interdict").[16] Conceivably, one of the parties knew he was in the wrong and decided he had better obey the praetor's interdict. If so, that was the end of the matter.[17] Suppose, however, he chose to brazen it out or, indeed, sincerely believed himself to be in the right.

The next step was to bring matters to a head. Accordingly, on a prearranged day the parties would commit a symbolic act of violence (vis ex conventu)[18] e.g. pretending to expel each other from the land. That, for the one in the wrong, must have been a formal disobedience of the praetor's order. Each party now challenged the other to a wager by which he had to pay his adversary a sum of money if it was he who had disobeyed the interdict. (This way of settling disputes in Rome — by having a wager on the result — was called agere per sponsione).[19] The agere per sponsonie was sent off to be tried by a iudex (akin to a one-man jury, usually a prominent citizen),[20] who in due course delivered his decision.[21] Meanwhile, the right to interim possession of the land was auctioned to whichever of the two contestants was the highest bidder, on his promise to pay his adversary the rent if he turned out to be in the wrong.

Roman litigation was not for the faint-hearted. Getting one's opponent into court at all could be difficult, and arguably praetors "were nothing more than politicians, frequently incompetent, open to bribery, and largely insulated against suits for malfeasance".[22] A litigant could frustrate the interdict process by omitting to take part in its rituals. When that happened, however, it was possible to obtain a secondary interdict by which he lost the case at once.[23]

Advantages of the interdict

Although the interdict neither conferred nor recognised any proprietary right, the party who prevailed had achieved three important advantages.

First, he enjoyed peaceful possession of the land against his adversary for the time being. Secondly, although his opponent might yet get the land — by bringing a vindicatio — the case had to be proved. This was important since it assigned the burden of proof. Thirdly, and in practice, his opponent might not trouble to take it further. Then, the party left in possession looked very like the real owner. As time went by it must have become more and more difficult to prove he was not.

In sum, by peaceful, open and unlicensed possession of land a party did not acquire ownership, but he did acquire practical advantages.

The Roman doctrine about establishing possession (not ownership) may seem slightly elusive for those brought up in the Anglophone common law[24] where it is trivially obvious that a good title to land can indeed be acquired by mere occupation (e.g. "squatters' rights"). However, it was not so in Roman law which drew a sharp line between ownership and possession. Except in special cases, mere occupation of land could not confer ownership.[25]

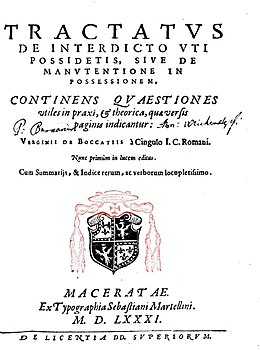

Later knowledge: the text of the edict

Although Gaius' text was imperfectly known to early modern Europeans, because it was lost and not rediscovered until 1816,[26] they knew the edict in the later recension by Justinian.[27] The interdict's name uti possidetis was a conventional abbreviation of the wording of the praetorial edict:

Uti eas aedes, quibus de agitur, nec vi nec clam nec precario alter ab altero possidetis, quo minus ita possideatis, vim fieri veto. De cloacis hoc interdictum non dabo: neque pluris quam quanti res elit; intra annum, quo primum experiundi potestas fuerit, agere permittan. (Dig. 43, 17, 1)

which has been translated

Whichever party has possession of the house in question, without having acquired it either by violence, or clandestinely, or by leave and licence of the adversary, the violent disturbance of his possession I prohibit. Sewers are not included in this interdict. The value of the thing in dispute and no more may be recovered, and I will not allow a party to proceed in this way except within the first year of days available for procedure (annus utilis).[28]

Much later, when it came to be adopted in international law the abbreviation was represented as Uti possidetis, ita possideatis ("as you possess, so may you possess"), whereby "possession became ten-tenths of the law", said to be a perversion of the Roman doctrine.[29]

Uti possidetis as a doctrine for the acquisition of territory in international law

From Roman private law, uti possidetis was transposed to international law as an assertion of sovereignty over territory, although the analogy was misleading.[30][31][32]

European powers, when they sought to justify their acquisition of territory in America and elsewhere, based their claims on a variety of legal concepts. One argument was that the new lands were terra nullius (belonging to nobody) and so could be acquired by occupation. But some prominent European jurists and theologians, like Francisco de Vitoria, rejected this, arguing that the lands did have owners: the indigenous peoples.[33] However, since the European powers were not seeking to justify themselves to the indigenous people, but to their European rivals, all they needed to show was a better claim, not an absolute one. Here they found the Roman law uti possidetis analogy valuable.[34]

Apparently it was first devised by the Portuguese diplomat Luís da Cunha in order to justify his country's claims to territory in colonial South America, though some have attributed the idea to the Luso-Brazilian diplomat Alexandre de Gusmão.[35]

While Spanish-American states may have been content to draw mutual boundaries by adopting the internal administrative divisions of the old Spanish Empire (see uti possidetis juris, below), this was not done as between Portuguese-America (Brazil) and the Spanish-American polities,[36] and was not possible. Explained John Bassett Moore:

There can be no more conclusive proof of the futility of the attempts made by Portugal and Spain to fix the limits of their dominions in South America than the fact that they left to their successors no treaty by which those limits purported to be determined.[37]

The Brazilian frontier movement into Spanish-claimed lands

In 1494 Spain and Portugal agreed to modify the 1492 papal bull which divided the world into two spheres of influence, with each country agreeing that it would respect the other's acquisitions on either side of an imaginary line. The Treaty of Tordesillas modified this imaginary line running from pole to pole: Spain was to have the lands to the west of that line, Portugal to the east.[38][39] Shortly afterwards, and around the same time, expeditions from both countries discovered South America.[40] As the new continent was explored it was gradually realised that the Tordesillas line, though rather vague,[41] gave Portugal only a corner of it, the vast majority going to Spain.[42][43]

Despite that, for the next 400 years Portuguese America, and its successor Brazil, expanded relentlessly in a generally westwards direction, deep into the lands claimed by Spain and its successors. Summarised E. Bradford Burns:

From a few village nuclei and plantations in the mid-sixteenth century clinging tenuously to the shores of the South Atlantic Ocean, first the Luso-Brazilians and, after 1822, the Brazilians crept westward and northwestward to the foothills of the mighty Andes Mountains by 1909. The frontier movement triumphed at the territorial expense of eleven neighboring [Hispanic] nations and colonies... Just in the period 1893–1909 alone Brazil swallowed up territory equal in size to Spain and France combined.[44]

Today Brazil comprises about half the continent.

-

(a) The Tordesillas Line (1494) gave Portugal only the eastern corner of South America, but Portuguese settlers ignored it.

-

(b) 400 years later. Brazil's expansion was achieved by enterprising frontiersmen and its principle uti possidetis.

The Portuguese got an early start owing to Spanish acquiescence. Although Portugal and Spain legally were separate kingdoms, the same Spanish dynasty sat on both thrones from 1580 to 1640. Portuguese settlers ignored the Tordesillas limit, and the Spanish crown did not object to their incursions. Thus, by mid 17th century – see map (a) – the Portuguese had established incursive footholds around the mouth of the Amazon and along the south Atlantic coast.[45]

There were too few Portuguese men to conquer the vast lands of Brazil by themselves[46] and almost no Portuguese women[47] went there at first. In effect, sectors of the indigenous people were co-opted. The country was opened up by bands of entrepreneurs.[48] The most famous of these are the bandeirantes, who searched for wealth: Indians to enslave, gold or diamonds. Though generally loyal to the Portuguese king, most bandeirantes were mamelucos (of mixed race) or perhaps Indians; illiterate; and extremely poor;[49] speaking Tupi rather than Portuguese amongst themselves.[50] Some bandeira commanders were black. The wilderness – where they endured severe hardships, and where they hoped to find riches – gripped their imagination.[51][52] Bandeirismo in one form or another was to persist into the 19th century.[53]

After the restoration of an independent Portuguese monarchy, the Portuguese interpreted the Tordesillas treaty creatively. Their version would have given them not only Patagonia, the River Plate and Paraguay, but even silver-rich Potosí in Upper Peru.[42] Modern research has revealed that their cartographers deliberately distorted maps to convince the Spanish they occupied more land to the east than was the case.[54][55][56]

By 1750, the Luso-Brazilians, employing their "indirect method of conquest", had tripled the extension of Portuguese America beyond that allowed by the Treaty of Tordesillas.[57] This method was to occupy the land with people and apply their version of the Roman doctrine of uti possidetis. In the Portuguese view this trumped Spanish paper claims – such as, under the Treaty of Tordesillas – because, as time went by, they became obsolete and no longer reflected reality. Today it might be called facts on the ground.

Portugal articulated its uti possidetis principle in the negotiations leading up to the Treaty of Madrid (1750), and this treaty broadly accepted that lands possessed by Portugal should continue to be so. The Treaty of Tordesillas was annulled.[58][59]

This new treaty did not stop continuing Luso-Brazilian expansion. The Marquis of Pombal, who virtually ruled the Portuguese Empire, instructed:

As the power and wealth of every country consists principally in the number and multiplication of the people who inhabit it ... this number and multiplication of people is most indispensable now on the frontiers of Brazil.

Since there were not enough native Portuguese to populate the frontiers (he wrote), it was essential to abolish "all differences between Indians and Portuguese", to attract the Indians from the Uruguay missions, and encourage their marriage with Europeans. The Jesuit missions among the Guaraní Indians stood in the way of this plan, and Pombal had the Jesuits expelled from the Portuguese empire in 1759.[60] In The Undrawn Line: Three Centuries of Strife on the Paraguayan-Mato Grosso Frontier, John Hoyt Williams wrote:

When the Treaty of Madrid was signed in 1750, separating the Spaniards and Portuguese from each other's throats, it established the high-minded principle of uti possidetis as a basis of territorial settlement. Intended to be an even-handed manner of recognizing the territory actually held (rather than merely claimed) by each of the contestants, in reality it touched off complex and bitter maneuvers to grab as much of the unmapped wilderness as possible before demarcation teams could arrive and begin to plot precise imperial limits. Further, there was great difficulty concerning which rivers were where, in which direction they flowed, and in what form they were spelled. Some rivers were searched for for years and never found.[61]

There were subsequent treaties between Portugal and Spain but for various reasons they never succeeded in defining a frontier between their American possessions.[62] Boundary disputes between their respective successor states had to be resolved by recourse to the factual uti possidetis.[63][64]

Brazil after it achieved its independence continued with the same principles, demanding that all territorial questions be decided on the principle of uti possidetis de facto.[65] In treaties between Brazil and (respectively) Uruguay (1851), Peru (1852), Venezuela (1852), Paraguay (1856), the Argentine Confederation (1857), and Bolivia (1867), the uti possidetis de facto principle was adopted.[66]

Africa

A similar principle, called the principle of effective occupation, was adopted by European powers e.g. at the Berlin Conference (1884–85). It was followed by the Scramble for Africa.

Peace treaties

Classical international law

When two states had been at war, the ensuing peace treaty was interpreted to mean that each party got a permanent right to the territory it occupied at the conclusion of hostilities, unless the contrary was expressly stipulated. Probably the most influential 19th century textbook, Henry Wheaton's Elements of International Law, asserted (in text virtually unchanged through successive editions for 80 years):[67]

The treaty of peace leaves everything in the state in which it found it – according to the principle of uti possidetis – unless there be some express stipulation to the contrary. The existing state of possession is maintained, except so far as altered by the terms of the treaty. If nothing be said about the conquered country or places, they remain with the conqueror, and his title cannot afterwards be called in question. During the continuance of the war, the conqueror in possession has only a usufructuary right, and the latent title of the former sovereign continues, until the treaty of peace, by its silent operation, or express provisions, extinguishes his title for ever.

This was only a default rule, however, for usually states were careful to specify explicitly in the peace treaty.[68]

Sometimes a war would cease without a peace treaty. (For example, in the Spanish American wars of independence the fighting stopped in 1825, but Spain did not formally recognise the new republics' independence for a generation.) In such cases it was doubtful whether the losing side was deemed (1) to assert the status quo ante bellum or (2) to concede the uti possidetis, but most authors favoured the latter alternative.[69]

Current position

The classical doctrine that victory in war gave good title to conquered territory was modified in the 20th century. The League of Nations Covenant of 1919, while it required states to resort to conflict resolution, did permit recourse to war. However the 1928 Kellogg–Briand Pact, ratified by most of the world's independent states, banned aggressive war; it was the basis on which the World War II war criminals were prosecuted in the Nuremberg and Tokyo Trials. Its essentials were reproduced in the United Nations Charter (1945). By Article 2(4):

All Members shall refrain in their international relations from the threat or use of force against the territorial integrity or political independence of any State, or in any other manner inconsistent with the Purposes of the United Nations

although Article 51 does allow self-defence.[70]

A corollary is said to be that international law does not recognise forcible territorial acquisitions, and a treaty procured by force or the threat of force is void;[71] in other words, the uti possidetis interpretation of peace treaties is now obsolete.[30] However, the position of a state which fights in self-defence and recovers territory previously lost to the aggressor does not appear to have been discussed.

Uti possidetis juris

This is a method of establishing international boundaries based on anterior legal divisions. "Stated simply, uti possidetis provides that states emerging from decolonization shall presumptively inherit the colonial administrative borders that they held at the time of independence".[72] The new states may be able to modify the old borders by mutual agreement with their neighbours.[73]

Originating after the breakup of the Spanish empire in America, it was there assumed to be possible "by a careful study of Spanish decrees, to trace a definite line of division between the colonial administrative units as of the period of independence". Hence the new states, when settling their mutual boundaries, quite often instructed arbitrators to use the uti possidetis at the date of independence. In reality, it turned out that a definite historical line could rarely be found.[74] Later, the principle was extended to the newly independent African states, and it has been applied to the dissolution of Yugoslavia and the Soviet Union.[75]

The doctrine of uti possidetis juris has been criticised as colliding with the principle of self-determination.[76] It has been argued that instead of promoting definite international frontiers it makes matters worse.[77] Castellino and Allen have argued that many of the modern separatist conflicts or tribal conflicts, such as Biafra, East Timor, Katanga, Kosovo, and Rwanda, can be traced to blind insistence on such artificial borders.[78]

References and notes

- ^ Poste & Whittuck 1904, p. 618.

- ^ Scott 2011, pp. 23, 26–30.

- ^ "And as it is far more advantageous to possess than to claim the possession; there is generally, indeed, nearly always, a great effort made to obtain the possession. The advantage of possessing consists in this, that even though the thing be not his who possesses it, yet if the plaintiff cannot prove that it is his, the possession remains where it is. and, for this reason, when the rights of both parties are doubtful, it is usual to decide against the claimant." JUST. IV, xv, §5 (Mears 1882, p. 562).

- ^ Poste & Whittuck 1904, pp. xxxi–xxxii, 592.

- ^ Watson 1970, pp. 107, 106, 109–110.

- ^ Muirhead 1899, pp. 205–6.

- ^ Moore 1913, pp. 5–6.

- ^ Source: Krueger and Studemund's apograph of the Verona palimpsest of Gaius' Institutes as reproduced in Poste & Whittuck 1904, pp. ii, 584.

- ^ Poste & Whittuck 1904, p. 584).

- ^ Poste & Whittuck 1904, p. 585.

- ^ Maybe he had got it by force from a third party; but if he was not before the praetor complaining, it was of no present concern.

- ^ Berger 1953, p. 512.

- ^ Mears 1882, p. 562.

- ^ Poste & Whittuck 1904, p. 610.

- ^ Benton & Straumann 2010, pp. 17, 30.

- ^ So called, wrote Gaius, "because the footing of both parties is equal, neither being exclusively plaintiff or defendant, but both playing both parts, and both being addressed by the praetor in identical terms." (Poste & Whittuck 1904, p. 587.)

- ^ Muirhead 1899, pp. 347.

- ^ Berger 1953, p. 76.

- ^ Berger 1953, pp. 357–8.

- ^ Berger 1953, p. 518.

- ^ Muirhead 1899, pp. 347–8.

- ^ Schiller 1968, pp. 506–7.

- ^ Muirhead 1899, p. 348.

- ^ Gordley & Mattei 1996, p. 300.

- ^ Lesaffer 2005, pp. 40–1, 43, 45, 47. Ownership might be acquired by usucaption but this required a defective title, not no title at all.

- ^ Poste & Whittuck 1904, p. lii.

- ^ Benton & Straumann 2010, p. 18.

- ^ Poste & Whittuck 1904, p. 599.

- ^ Ratner 1996, p. 593.

- ^ a b Nessi 2011, p. 626 §2.

- ^ Fisher 1933, p. 415.

- ^ Moore 1913, p. 8.

- ^ Benton & Straumann 2010, pp. 1, 4, 15, 16, 17, 20–5, 38.

- ^ Benton & Straumann 2010, pp. 3, 17, 30, 38.

- ^ Furtado 2021, pp. 109–135, see especially pp.113, 119, 127–9, 130, 131 and 133..

- ^ Lalonde 2001, p. 33 and n.(31).

- ^ Moore 1904, p. 2.

- ^ Ozmańczyk 2003, pp. 2329–2230.

- ^ A translation of the Treaty and background explanation is in Greenlee 1945, pp. 158–59 and passim.

- ^ Christopher Columbus, third voyage, 1498 (Spain); Pedro Álvares Cabral, 1500 (Portugal). There is a hypothesis that the Portuguese discovered Brazil before 1500, but the theory has been criticised: Marchant 1945, pp. 296–300

- ^ The line was supposed to run 370 leagues west of the Cape Verde islands, but the Treaty did not specify which of those islands. Nor did it specify which sort of league: several kinds were in use. (Tambs 1966b, p. 166)

- ^ a b Tambs 1966b, p. 166.

- ^ "Actually the line of Tordesillas in the New World probably should have run between Belém do Pará and Santos": Tambs 1966b, p. 166.

- ^ Burns 1995, pp. 1, 3.

- ^ Tambs 1966b, p. 168.

- ^ Russell-Wood 2005, p. 356.

- ^ Hennessy 1993, p. 17.

- ^ Russell-Wood 2005, p. 363.

- ^ Evans & Dutra e Silva 2017, pp. 121–126, 129–130.

- ^ Hennessy 1993, p. 32.

- ^ Evans & Dutra e Silva 2017, p. 129-133.

- ^ Burns 1995, p. 2.

- ^ Russell-Wood 2005, p. 362.

- ^ Mullan 2001, p. 156.

- ^ Tambs 1966b, p. 174.

- ^ Furtado 2021, p. 134.

- ^ Tambs 1966b, pp. 165, 178.

- ^ Furtado 2021, pp. 111–113, 118–121, 127–130, 131–134.

- ^ Moore 1913, p. 17.

- ^ Maxwell 1968, pp. 619, 628, 629.

- ^ Williams 1980, p. 20.

- ^ The Treaty of Madrid 1750 was annulled and replaced by the Treaty of San Idelfonso 1777. But the 1777 Treaty did not define the boundaries between the Spanish and Portuguese empires; it merely provided for boundary commissioners to survey the disputed areas and resolve them. Portugal delayed sending commissioners to the disputed areas and, before anything could happen, Spain attacked Portugal during the Napoleonic wars – the so-called War of the Oranges, which was extended to the South American colonies. By the Peace of Badajoz (1801) no provision was made for the restoration of the status quo ante bellum. The 1777 Treaty was admittedly annulled. (Moore 1904, pp. 5–6)

- ^ Moore 1904, pp. 2–8.

- ^ Tambs 1966b, pp. 175–8.

- ^ Tambs 1966a, p. 255.

- ^ Moore 1904, pp. 6–7.

- ^ From the first edition of 1836 (Wheaton 1836, p. 370) to 1916 (Phillipson 1916a, p. 807).)

- ^ Phillipson 1916b, p. 220–222.

- ^ Phillipson 1916b, pp. 4–6.

- ^ Crawford 2012, pp. 744–746.

- ^ Crawford 2012, pp. 757–58.

- ^ Ratner 1996, p. 590.

- ^ Nessi 2011, p. 627 §7.

- ^ Fisher 1933, pp. 415, 416.

- ^ Nessi 2011, p. 627 §6.

- ^ Nessi 2011, p. 630 §19.

- ^ Ratner 1996, pp. 590–624.

- ^ Epps 2004, pp. 869–70.

Sources

- Benton, Lauren; Straumann, Benjamin (2010). "Acquiring Empire by Law: From Roman Doctrine to Early Modern European Practice". Law and History Review. 28 (1). American Society for Legal History: 1–38. doi:10.1017/S0738248009990022. S2CID 143079931.

- Berger, Adolf (1953). "Encyclopedic Dictionary of Roman Law". Transactions of the American Philosophical Society. 43 (2). Philadelphia: The American Philosophical Society: 333–809. doi:10.2307/1005773. hdl:2027/uva.x000055888. JSTOR 1005773. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- Burns, E. Bradford (1995). "Brazil: Frontier and Ideology". Pacific Historical Review. 64 (1). University of California Press: 1–18. doi:10.2307/3640332. JSTOR 3640332.

- Crawford, James, ed. (2012). Brownlie's Principles of Public International Law (8th ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-965417-8.

- Epps, Valerie (2004). "Review: Title to Territory in International Law: A Temporal Analysis by Joshua Castellino and Steve Allen". The American Journal of International Law. 98 (4). Cambridge University Press: 869–872. doi:10.2307/3216726. JSTOR 3216726. S2CID 230237911.

- Evans, Sterling; Dutra e Silva, Sandro (2017). "Crossing the Green Line: Frontier, environment and the role of bandeirantes in the conquering of Brazilian territory". Fronteiras: Journal of Social, Technological and Environmental Science. 6 (1). Universidade Evangélica de Goiás: 120–142. doi:10.21664/2238-8869.2017v6i1.p120-142.

- Fisher, F. C. (1933). "The Arbitration of the Guatemalan-Honduran Boundary Dispute". The American Journal of International Law. 27 (3). Cambridge University Press: 403–427. doi:10.2307/2189971. JSTOR 2189971. S2CID 147670425.

- Furtado, Junia Ferreira (2021). "Portuguese America under Foreign Threat and the Creation of the Concept of uti possidetis in the First Half of the 18th Century". Espacio, Tiempo y Forma — serie IV Historia Moderna. 34 (34): 109–142. doi:10.5944/etfiv.34.2021.29359. Retrieved 29 March 2022.

- Gordley, James; Mattei, Ugo (1996). "Protecting Possession". The American Journal of Comparative Law. 44 (2). Oxford University Press: 293–334. doi:10.2307/840711. JSTOR 840711.

- Greenlee, William B. (1945). "The Background of Brazilian History". The Americas. 2 (2): 151–164. doi:10.2307/978215. JSTOR 978215.

- Hennessy, Alistair (1993). "The Nature of the Conquest and the Conquistadors" (PDF). Proceedings of the British Academy. 81: 5–36. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- Lalonde, Suzanne (2001). "Uti Possidetis: Its Colonial Past Revisited". Revue Belge de Droit International / Belgian Review of International Law. 34 (1). E-ditions BRUYLANT, Bruxelles: 23–99. Retrieved 15 April 2022.

- Lesaffer, Randall (2005). "Argument from Roman Law in Current International Law: Occupation and Acquisitive Prescription". The European Journal of International Law. 16 (1): 25–58. doi:10.1093/ejil/chi102.

- Marchant, Alexander (1945). "The Discovery of Brazil: A Note on Interpretations". Geographical Review. 35 (2): 296–300. Bibcode:1945GeoRv..35..296M. doi:10.2307/211482. JSTOR 211482.

- Maxwell, Kenneth R. (1968). "Pombal and the Nationalization of the Luso-Brazilian Economy". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 48 (4). Duke University Press: 608–631. doi:10.2307/2510901. JSTOR 2510901.

- Mears, T. Lambert (1882). The Institutes of Gaius and Justinian. London: Stevens and Sons. Retrieved 30 March 2022.

- Moore, John Bassett (1904). Brazil and Peru Boundary Question. New York: Knickerbocker Press. Retrieved 4 April 2022.

- Moore, John Bassett (1913). Costa Rica-Panama Arbitration: Memorandum on Uti Possidetis. Rosslyn, VA: The Commonwealth Co. Retrieved 20 February 2022.

- Muirhead, James (1899). Goudie, Henry (ed.). Historical Introduction to the Private Law of Rome (2nd ed.). London: A & C Black. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- Mullan, Anthony Páez (2001). "Review: La Cartografia Iberoamericana by M. Luisa Martín-Merás, Max Justo Guedes and José Ignacio González Leiva". Imago Mundi. 53: 156. JSTOR 1151583.

- Nessi, Giuseppe (2011). "Uti possidetis Doctrine" (PDF). In Wulfrum, Rüdiger (ed.). The Max Planck Encyclopedia of International Law. Vol. X. Oxford. Retrieved 3 April 2022.

- Ozmańczyk, Edmund (2003). Encyclopedia of the United Nations and International Agreements. Vol. 4 (3rd ed.). London: Routledge. ISBN 0415939240.

- Phillipson, Coleman, ed. (1916a). Wheaton's Elements of International Law (5th English ed.). London: Stevens. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- Phillipson, Coleman (1916b). Termination of War and Treaties of Peace. New York: E.P. Dutton. Retrieved 5 April 2020.

- Poste, Edward; Whittuck, E.A. (1904). Gai Institvtiones or Institutes of Roman Law by Gaius (4th ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Retrieved 21 March 2022.

- Ratner, Steven R. (1996). "Drawing a Better Line: UTI Possidetis and the Borders of New States". The American Journal of International Law. 90 (4): 590–624. doi:10.2307/2203988. JSTOR 2203988. S2CID 144936970.

- Russell-Wood, A. J. R. (2005). "Introduction: New Directions in Bandeirismo Studies In Colonial Brazil". The Americas. 61 (3, Rethinking Bandeirismo in Colonial Brazil). Cambridge University Press: 353–371. doi:10.1353/tam.2005.0048. JSTOR 4490919. S2CID 201789918.

- Schiller, A. Arthur (1968). "Review: Roman Litigation by J. M. Kelly". The American Journal of Philology. 89 (4). The Johns Hopkins University Press: 506–508. doi:10.2307/292842. JSTOR 292842.

- Scott, Helen (2011). "Absolute Ownership and Legal Pluralism in Roman Law: Two Arguments". Acta Juridica. 2011 (1): 23–34. hdl:10520/EJC124854. Retrieved 16 April 2022.

- Tambs, Lewis A. (1966a). "Rubber, Rebels, and Rio Branco: The Contest for the Acre". The Hispanic American Historical Review. 46s (3). Duke University Press: 254–273. doi:10.2307/2510627. JSTOR 2510627.

- Tambs, Lewis A. (1966b). "Brazil's Expanding Frontiers". The Americas. 23 (2). Cambridge University Press: 165–179. doi:10.2307/980583. JSTOR 980583. S2CID 147574561.

- Watson, Alan (1970). "The Development of the Praetor's Edict". The Journal of Roman Studies. 60: 105–119. JSTOR 299417.

- Wheaton, Henry (1836). Elements of International Law with a sketch of the history of the science. Philadelphia: Carey, Lea and Blanchard. Retrieved 7 April 2022.

- Williams, John Hoyt (1980). "The Undrawn Line: Three Centuries of Strife on the Paraguayan-Mato Grosso Frontier". Luso-Brazilian Review. 17 (1). University of Wisconsin Press: 17–40. JSTOR 3513374.