You Only Live Twice (novel)

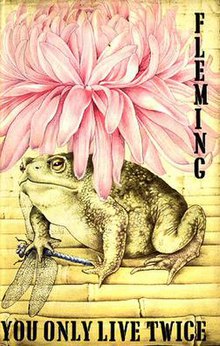

First edition cover | |

| Author | Ian Fleming |

|---|---|

| Cover artist | Richard Chopping |

| Language | English |

| Series | James Bond |

| Genre | Spy fiction |

| Published | 26 March 1964 |

| Publisher | Jonathan Cape |

| Publication place | United Kingdom |

| Media type | Print (hardback & paperback) |

| Pages | 256 |

| Preceded by | On Her Majesty's Secret Service |

| Followed by | The Man with the Golden Gun |

You Only Live Twice is the eleventh novel and twelfth book in Ian Fleming's James Bond series.[a] It was first published by Jonathan Cape in the United Kingdom on 26 March 1964 and quickly sold out. It was the last novel Fleming published in his lifetime. He based his book in Japan after a stay in 1959 as part of a trip around the world that he published as Thrilling Cities. He returned to Japan in 1962 and spent twelve days exploring the country and its culture.

You Only Live Twice begins eight months after the murder of Tracy Bond, James Bond's wife, which occurred at the end of the previous novel, On Her Majesty's Secret Service (1963). Bond is drinking, gambling heavily and making mistakes on his assignments when, as a last resort, he is sent to Japan on a semi-diplomatic mission. While there he is challenged by the head of the Japanese Secret Service to kill Dr. Guntram Shatterhand. Bond realises that Shatterhand is Ernst Stavro Blofeld—the man responsible for Tracy's death—and sets out on a revenge mission to kill him and his wife, Irma Bunt. The novel is the concluding chapter of the "Blofeld Trilogy", which had begun in 1961 with Thunderball.

The novel deals with the change in Bond from an emotionally shattered man in mourning, to a man of action bent on revenge, to an amnesiac living as a Japanese fisherman. Through the mouths of his characters, Fleming also examines the decline of post-Second World War British power and influence, particularly in relation to the United States. The book was popular with the public, with pre-orders in the UK totalling 62,000; reviewers were more muted in their reactions, many criticising the extended sections of what they considered a travelogue.

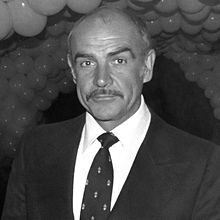

The story was serialised in the Daily Express newspaper—where it was also adapted for comic strip format—and in Playboy magazine. In 1967 it was released as the fifth entry in the Eon Productions James Bond film series, starring Sean Connery as Bond; elements of the story were also used in No Time to Die (2021), the twenty-sixth film in the Eon Productions series. The novel has also been adapted as a radio play and broadcast on the BBC.

Plot

After the wedding-day murder of his wife, Tracy,[b] the Secret Service agent James Bond goes into a decline, drinking and gambling heavily, making mistakes and turning up late for work. His superior in the Secret Service, M, had been planning to dismiss Bond, but decides to give him a last-chance opportunity to redeem himself by assigning him to the diplomatic branch of the organisation. Bond is subsequently re-numbered 7777 and handed an "impossible" mission: persuading the head of Japan's secret intelligence service, Tiger Tanaka, to share a decoding machine codenamed Magic 44 and so allow Britain to obtain information from encrypted radio transmissions made by the Soviet Union. In exchange, the Secret Service will allow the Japanese access to one of their own information sources.

Bond is introduced to Tanaka—and to the Japanese lifestyle—by an Australian intelligence officer, Dikko Henderson. When Bond raises the purpose of his mission with Tanaka, it transpires that the Japanese have already penetrated the British information source and Bond has nothing left to bargain with. Instead, Tanaka asks Bond to kill Dr. Guntram Shatterhand, who operates a politically embarrassing "Garden of Death" in a rebuilt ancient castle on the island of Kyushu; people visit the grounds, replete with poisonous plants, to kill themselves. After examining photos of Shatterhand and his wife, Bond realises that the couple are actually Tracy's murderers, Ernst Stavro Blofeld and Irma Bunt. Bond gladly takes the mission, keeping his knowledge of Blofeld's identity a secret so that he can exact revenge for his wife's death. Made up and trained by Tanaka, and aided by the former Japanese film star Kissy Suzuki, Bond attempts to live and act as a mute Japanese coal miner in order to penetrate Shatterhand's castle. Tanaka gives Bond the cover name "Taro Todoroki" for the mission.

After infiltrating the Garden of Death and the castle where Blofeld spends his time dressed in the costume of a Samurai warrior, Bond is captured and identified as a British secret agent. After nearly being executed, Bond exacts revenge on Blofeld in a duel, the former with a wooden staff and the latter armed with a sword. Bond eventually kills Blofeld by strangling him in a fit of violent rage; he then blows up the castle. Upon escaping, he suffers a head injury, leaving him an amnesiac living as a Japanese fisherman with Kissy. Meanwhile, the rest of the world believes him dead, and his obituary appears in the newspapers.

While Bond's health improves, Kissy conceals his true identity to keep him forever to herself. Kissy eventually sleeps with Bond and becomes pregnant, and hopes that Bond will propose marriage after she finds the right time to tell him about her pregnancy. Bond reads scraps of newspaper and fixates on a reference to Vladivostok, making him wonder if the far-off city is the key to his missing memory; he tells Kissy he must travel to Russia to find out.

Background and writing history

By January 1963 Ian Fleming had published ten books of the Bond series in ten years: nine novels and a collection of short stories.[a] An eleventh book, On Her Majesty's Secret Service, was being edited and prepared for production; it was released on 1 April 1963.[2][3] Fleming travelled to his Goldeneye estate in Jamaica in January 1963 to write You Only Live Twice, which he did over two months.[4][3] He followed his usual practice, which he later outlined in Books and Bookmen magazine: "I write for about three hours in the morning ... and I do another hour's work between six and seven in the evening. I never correct anything and I never go back to see what I have written ... By following my formula, you write 2,000 words a day."[5] Towards the end of February 1963 he wrote to his friend and copy editor William Plomer: "I have completed Opus XII save for 2 or 3 pages and am amazed that the miracle should have managed to repeat itself—the 65,000 odd words that is, and pretty odd some of them are!"[6] When he had nearly completed writing You Only Live Twice, Fleming wrote to his friend Richard Hughes, the Far Eastern correspondent of The Sunday Times:

I'm grinding away at Bond's latest but the going gets harder and harder and duller and duller and I don't really know what I'm going to do with him. He's become a personal—if not a public—nuisance. Anyway he's had a good run, which is more than most of us can say. Everything seems too much trouble.[7]

The original manuscript was 170 pages and, of all Fleming's works, it was the one that had least revisions prior to publication.[3] After returning to England, Fleming revised the manuscript while staying in Kent. This included contacting the company secretary of The Times to ask permission to use their masthead above Bond's fictional obituary; the matter was complicated by the presence of the royal arms.[8][c]

You Only Live Twice is the last book completed by Fleming before his death and the last that was published in his lifetime;[9] he died five months after the UK release of the novel.[10][11] The story is the third part of what is known as the "Blofeld trilogy",[12] coming after Thunderball, where SPECTRE is introduced, and On Her Majesty's Secret Service, which ends with Blofeld involved in the murder of Bond's wife.[3] Fleming's biographer Matthew Parker considers the novel's mood to be dark and claustrophobic. This reflected Fleming's increasing melancholia, partly as a result of the recent news that he had, at most, five years to live, following his heart attack in April 1961.[4][11][13]

Although Fleming did not date the events within his novels, John Griswold and Henry Chancellor—both of whom wrote books for Ian Fleming Publications—have identified timelines based on episodes and situations within the novel series as a whole. Chancellor put the events of You Only Live Twice between 1962 and 1963; Griswold is more precise and considers the story to have taken place between April 1962 and April 1963.[14][15] The story was written after the film version of Dr. No was released in 1962, and Bond's personality had developed from that in the earlier novels, influenced by the screen persona. Fleming added the elements of humour in Sean Connery's filmic depiction of Bond to You Only Live Twice, giving Bond a more relaxed manner.[16][17]

Fleming based his novel in Japan after a three-day visit in 1959, as part of a trip around world cities for The Sunday Times. He later wrote his travel book Thrilling Cities (1963) based on the result.[18][12] He was enthralled by the country, which led to its use as the location for the novel. He revisited Japan in 1962, spending twelve days there. As with his first trip, he was accompanied on his trip around the country by two journalists: Hughes and Torao "Tiger" Saito.[3][18]

Development

Inspirations

The novel contains a fictional obituary of Bond, supposedly published in The Times, which provided the first details from Fleming of Bond's early life.[19] Many of the traits were Fleming's own. This included Bond's expulsion from Eton College, which was akin to Fleming's withdrawal from the college by his mother, according to the journalist Ben Macintyre.[20] As with a number of the previous Bond stories, You Only Live Twice used names of individuals and places that were from Fleming's past. Bond's mother, Monique Delacroix, was named after two women in Fleming's life: Monique Panchaud de Bottens, a Swiss girl from Vich in the canton of Vaud, to whom Fleming was engaged in the early 1930s,[21] with Delacroix taken from Fleming's own mother, whose maiden name was Ste Croix Rose.[22]

Fleming named Bond's aunt "Charmian Bond": Charmian was the forename of Fleming's cousin who married his brother Richard.[22] Charmian's sister was called "Pet", which, when combined with a play on words from Monique Panchaud de Bottens, gives Pett Bottom, where Charmian lives.[22] Pett Bottom is also the name of a real place which amused Fleming when he stopped for lunch after a round of golf at Royal St George's Golf Club, Sandwich.[22] In the summer of 1963, shortly after completing the book, Fleming went to Montreux to visit the writer Georges Simenon; he tried to see Monique to reveal her part in his new book, but she refused to meet him.[23]

Blofeld's name comes from Tom Blofeld, a Norfolk farmer and a fellow member of Fleming's gentlemen's club Boodle's, who was a contemporary of Fleming's at Eton.[24][d] For Blofeld's pseudonym in the novel, Dr. Guntram Shatterhand, Fleming uses the name of an old café he had seen in Hamburg in 1959, "Old Shatterhand".[22] The café was named after a fictional character from a series of Western stories by the German writer Karl May. In his first draft, Fleming named the character Julius Shatterhand, but subsequently crossed it out in favour of Guntram.[26] The characterisation of him dressed as a samurai was taken from the sketch Fleming had come up with thirty-five years earlier for a character called Graf Schlick.[11]

Much of the background material for the novel—particularly the description of the country and Japanese culture—Fleming obtained during his two visits to Japan.[27] So much of the book is taken up with the description that the literary analyst LeRoy L. Panek considers the work to be a "semi-exotic travelogue".[28] Fleming's two companions on his trip, Richard Hughes and Tiger Saito, became Dikko Henderson and Tiger Tanaka in the book.[18][e] Fleming described Saito as "a chunky, reserved man with considerable stores of quiet humour and intelligence, and with a subdued but rather tense personality. He looked like a fighter—one of those war-lords of the Japanese films".[29] When planning the 1959 trip, Fleming told Hughes:

There would be no politicians, museums, temples, Imperial palaces, or Noh plays, let alone tea ceremonies. I wanted, I said, to see Mr Somerset Maugham, who had just arrived and was receiving a triumphal welcome; visit the supreme judo academy; see a sumo wrestling match; explore the Ginza; have the most luxurious Japanese bath; spend an evening with geishas; consult the top Japanese soothsayer; and take a day trip into the country. I also said that I wanted to eat large quantities of raw fish, for which I have a weakness, and ascertain whether sake was truly alcoholic or not.[30]

They managed to undertake all the events, except the sumo match. On a trip to a geisha house, Fleming's attendant geisha, Masami, served as the inspiration for Trembling Leaf, a geisha in the novel.[31] As Fleming noted when he visited a geisha house in Thrilling Cities, "Most foreigners do not have a correct understanding of the geisha. They are not prostitutes".[32]

Characters

The central character in the novel is James Bond.[33] He begins You Only Live Twice in a disturbed state, described by M as "going to pieces", following the murder of his wife Tracy eight months previously.[34] He has visited doctors, hypnotists and therapists and told them "I feel like hell. I sleep badly. I eat practically nothing. I drink too much and my work has gone to blazes. I'm shot to pieces. Make me better."[35] The historian Jeremy Black points out that it was a very different Bond to the character who lost Vesper Lynd at the end of Casino Royale.[13] Given a final chance by M to redeem himself with a difficult mission, Bond's character changes under the ministrations of Dikko Henderson, Tiger Tanaka and Kissy Suzuki.[36] The result, according to Raymond Benson—the author of the continuation Bond novels—is a Bond with a sense of humour and a purpose in life.[33] The book's penultimate chapter contains Bond's obituary, purportedly written by M for The Times. Fleming uses this to provide previously unrevealed biographical details of Bond's early life, including his parents' names and nationalities and Bond's education.[33]

The novelist and critic Kingsley Amis, in his examination of Fleming's stories, finds Bond a Byronic hero, seen as "lonely, melancholy, of fine natural physique which has become in some way ravaged, of similarly fine but ravaged countenance, dark and brooding in expression, of a cold or cynical veneer, above all enigmatic, in possession of a sinister secret".[37] By the close of You Only Live Twice, according to Amis, Bond has been transformed and has "acquired the most important single item in the Byronic hero's make-up, a secret sorrow over a woman, aggravated, as it should be, by self-reproach".[38]

Blofeld makes his third appearance in the Bond series in You Only Live Twice[12] and Benson notes that on this occasion he is mad and egocentric in his behaviour;[39] Tanaka refers to him as "no less than a fiend in human form",[40] and the cultural critic Umberto Eco considers the character to have "a murderous mania".[41] The Anglicist Christoph Lindner notes that Fleming, through Bond's dialogue, parallels Blofeld with Caligula, Nero and Hitler. Lindner continues that the crimes perpetrated are not against individuals per se, but entire nations, continents or "the entire human race itself".[42] The literary analyst LeRoy L. Panek considers the character to be a declining force in comparison to his appearance in Thunderball, and "is a paper figure ... in spite of the megalomaniac speeches".[43]

According to Benson, Kissy Suzuki is "a most appealing heroine" who falls in love with Bond.[33] Apart from being the mother of Bond's unborn child at the end of the book, Suzuki also acts as a "cultural translator" for Bond, helping explain the local traditions and customs; Quarrel had the same function in Dr. No and Live and Let Die.[44] The cultural historians Janet Woollacott and Tony Bennett consider her to be "the ideal Bond girl – natural, unaffected, totally lacking in deference, independent and self-reliant, yet also caring, loving, solicitous for Bond's well-being and willing to cater to his every need without making any demands in return".[45]

Eco identifies Tiger Tanaka as one of Fleming's characters with morals closer to those of traditional villains, but who act on the side of good in support of Bond; others of this type have included Darko Kerim (From Russia, with Love), Marc-Ange Draco (On Her Majesty's Secret Service) and Enrico Colombo ("Risico").[46] Similarly, Panek considers that Dikko Henderson "serves as an inspiration for Bond" because of what he sees as the character's "robust enjoyment of life—enjoyment of food, drink and women".[47] The Anglicist Robert Druce finds similarities in characters between Henderson and those of Draco and Darko, and observes that the nickname "Dikko" is a close echo of their names.[48]

Style

Much of You Only Live Twice is taken up with background information about Japan and its culture. Bond is not threatened for most of the novel, except the final thirty pages, when he comes into contact with Blofeld.[28] The Anglicist John Hatcher observes that the first 112 pages—in his edition of 212 pages—"read more like a hybrid travelogue/sociology textbook than a James Bond novel".[49][28][f] Being written from a western viewpoint for a western audience, Hatcher considers that the novel "is a comprehensive anthology of western tropes and stereotypes about Japan".[50] Panek identifies how, like in other of his novels, Fleming structures his storylines based on episodes which are then linked together by the narrative.[g] For his weaker books, Panel observes, Fleming's descriptive narrative becomes padding; with You Only Live Twice, which Panek says is one of the worst examples of Fleming's work, "this padding degenerates into incompetent travelogue".[51]

Benson describes the first two-thirds of the book as being in a high journalistic style, but from the point Bond is preparing to meet and battle Blofeld, Benson sees Fleming's writing becoming allegorical and epic, using Bond as a symbol of good against the evil of Blofeld.[9] Benson sees an increased use of imagery to reinforce this approach, to give an effect which is "horrific, dreamlike and surrealistic".[9]

Themes

Much in the novel concerns the state of Britain in world affairs. Black points out that the reason for Bond's mission to Japan is that the US did not want to share intelligence regarding the Pacific, which it saw as its "private preserve". As Black goes on to note, however, the defections of four members of MI6 to the Soviet Union had a major impact in US intelligence circles on how Britain was viewed.[13] The last of the defections was that of Kim Philby in January 1963,[52] while Fleming was still writing the first draft of the novel.[3] Black contends that the conversation between M and Bond allows Fleming to discuss the decline of Britain, with the defections and the 1963 Profumo affair as a backdrop.[53] After Tiger Tanaka's criticisms of Britain's weaknesses, Bond can point only to Nobel Prize winners and the ascent of Everest as a defence.[54] Bennet and Woollcott see that one of the roles Bond has in the novels "is to prove that there is still an elite in Britain, still a backbone to the English character".[55]

The theme of Britain's declining position in the world is also dealt with in conversations between Bond and Tanaka; Tanaka voices Fleming's own concerns about the state of Britain in the 1950s and early 60s.[56] Tanaka accuses Britain of throwing away the empire "with both hands";[57] this would have been a contentious situation for Fleming, as he wrote the novel as the Indonesia–Malaysia confrontation was breaking out (in December 1962), a direct challenge to British interests in the region.[53] Fleming's increasingly jaundiced views on America appear in the novel too,[58] through Bond's responses to Tiger's comments, and they reflect on the declining relationship between Britain and America: this is in sharp contrast to the warm, co-operative relationship between Bond and the CIA agent Felix Leiter in the earlier books.[53]

One of the main themes of You Only Live Twice is that of symbolic death and rebirth. This is echoed in the book's title and in Bond's attempt at a haiku, written in the style of Japanese poet Matsuo Bashō:[34][59]

You only live twice:

Once when you are born

And once when you look death in the face— You Only Live Twice, Chapter 11[60]

The rebirth in question is that of Bond, transformed from the heavy drinker with emotional problems, mourning his wife at the beginning of the book, to a man of action and then, after the death of Blofeld and the seeming death of Bond, to Taro Todoroki, the Japanese partner of Kissy Suzuki.[34] Druce observes that "in Kissy's care, Bond is symbolically reborn, while Kissy, his Sybilline tutor in the Japanese language, learns to love once more."[61]

As with several other Bond stories, the concept of Bond as Saint George against the dragon underlies the storyline to You Only Live Twice.[62][9][h] Tiger Tanaka twice overtly calls attention to this when he says to Bond "You are to enter this Castle of Death and slay the Dragon within", and then later asks:[64]

But, Bondo-san, does it not amuse you to think of that foolish dragon dozing all unsuspecting in his castle while St. George comes silently riding towards his lair across the waves? It would make the subject for a most entertaining Japanese print.[65]

This is, according to Druce, reinforced by Blofeld's staff being recruited from the Japanese "Black Dragon" society;[66] the organisation was described by Fleming as being formerly "the most feared and powerful secret society in Japan".[67] Druce also highlights a kimono Blofeld wears when addressing Bond, which is described thus: "the golden dragon embroidery, so easily to be derided as a childish fantasy, crawled menacingly across the black silk and seemed to spit real fire from over the left breast".[68][48]

Release and reception

Publication history

... high-flown and romanticized caricatures of episodes in the career of an outstanding public servant.

You Only Live Twice, Chapter 21[69]

You Only Live Twice was published in the UK on 16 March 1964 by Jonathan Cape;[70][71] the first edition was 256 pages long.[72] There were 62,000 pre-orders for the book,[73] a considerable increase over the 42,000 advance orders for the hardback first edition of On Her Majesty's Secret Service.[74] Richard Chopping, the cover artist for The Spy Who Loved Me, was engaged for the design.[70] In July 1963, Michael Howard of Jonathan Cape had written to Chopping about the artwork, saying, "If you could manage a pink dragonfly sitting on one of the flowers, and perhaps just one epicanthic eye peering through them, [Fleming] thinks that will be just splendid."[75] After searching for a toad along the banks of the River Colne, Chopping borrowed one from a neighbour's daughter.[76] His fee rose to 300 guineas for the cover[77] from the 250 guineas he received for The Spy Who Loved Me.[78][i]

You Only Live Twice was published in the US by New American Library in August 1964;[70] it was 240 pages long.[81] The book went on to The New York Times Best Seller list, where it remained for over twenty weeks; it was the eighth-bestselling novel of 1964 in the US.[82]

In July 1965 Pan Books published a paperback version of You Only Live Twice in the UK that sold 309,000 copies before the end of the year and 908,000 in 1966.[83] Since its initial publication the book has been re-issued in hardback and paperback editions, translated into several languages and, as at 2025, has never been out of print.[84][85] In 2023 Ian Fleming Publications—the company that administers all Fleming's literary works—had the Bond series edited as part of a sensitivity review to remove or reword some racial or ethnic descriptors. Although many of Fleming's racial epithets were removed from the novel, Fleming's description of the Japanese as "A violent people without a violent language" was retained. The release of the bowdlerised series was for the 70th anniversary of Casino Royale, the first Bond novel.[86][87]

Critical reception

The critic for The Times was largely unimpressed with You Only Live Twice, complaining that "as a moderate to middling travelogue what follows will just about do ... the plot with its concomitant sadism does not really get going until more than half way through".[72] In The Guardian, Francis Iles thought that Fleming was beginning to tire of Bond, and possibly of writing thrillers; he reasoned that only a quarter of the novel was what could be classed a thriller, and his enjoyment was further diminished by what he considered "the grossness of Bond's manners and his schoolboy obscenities".[88] Peter Duval Smith, in the Financial Times, believed that the setting of the novel was well done; he considered that Fleming "caught the exact 'feel' of Japan".[89] Maggie Ross, in The Listener, was a little dissatisfied, writing that the novel can be read as a thriller and that when a reader's interest waned, they could focus on the travelogue aspects of the book. She went on to say that "since not very much in the way of real excitement happens until the latter half of the book, perhaps it is better to ignore the whole thing".[90] Maurice Richardson, in The Observer, was critical of several aspects, saying that the "narrative is a bit weak, action long delayed and disappointing when it comes but the surround of local colour ... has been worked over with that unique combination of pubescent imagination and industry which is Mr. Fleming's speciality".[91]

Duval Smith thought that You Only Live Twice was not a successful novel, and that the problem lay with the depiction of Bond, as he "doesn't add up to a human being".[89] Malcolm Muggeridge, in Esquire magazine, wrote that "Bond can only manage to sleep with his Japanese girl with the aid of colour pornography. His drinking sessions seem somehow desperate, and the horrors are too absurd to horrify ... it's all rather a muddle and scarcely in the tradition of Secret Service fiction. Perhaps the earlier novels are better. If so, I shall never know, having no intention of reading them."[92] Robert Fulford, in the Toronto-based magazine Maclean's, noted that Bond's moral simplicity was one of the keys to the popularity of the series, although that also made the books appear trivial.[92] Charles Poore, writing in The New York Times, observed that Bond's mission "is aimed at restoring Britain's pre-World War II place among the powers of the world. And on that subject, above all others, Ian Fleming's novels are endlessly, bitterly eloquent".[81] The Boston Globe's Mary Castle opined that the agent's trip was "Escapism in the Grand Manner".[93]

Richardson found You Only Live Twice, although not the strongest of the Bond novels, to be very readable,[91] and the Belfast Telegraph considered that Fleming was "still in a class of his own".[92] Bookman saw You Only Live Twice as one of the stronger Bond novels.[70] Cyril Connolly, in The Sunday Times, wrote that the novel was "reactionary, sentimental, square, the Bond-image flails its way through the middle-brow masses, a relaxation to the great, a stimulus to the humble, the only common denominator between Kennedy and Oswald".[92] The Times thought that "though Mr. Fleming's macabre imagination is as interesting as ever, some of the old snap seems to have gone".[72] Dealing with the cliffhanger ending to the story, the reviewer wrote that "Mr. Fleming would keep us on tenterhooks, but at this rate of going even his most devoted admirers will free themselves before very long."[72] The critic for The Spectator felt that Fleming had taken too much of the films' humour and was writing a pastiche of his earlier work.[92]

Adaptations

You Only Live Twice was adapted for serialisation in the Daily Express on a daily basis from 2 March 1964 onwards.[71] The novel was also adapted as a daily comic strip in the same newspaper, and syndicated worldwide. The adaptation, written by Henry Gammidge and illustrated by John McLusky, ran from 18 May 1965 to 8 January 1966.[94] It was the final James Bond strip for Gammidge, while McClusky returned to illustrating the strip in the 1980s.[94] The strip was reprinted by Titan Books in The James Bond Omnibus Vol. 2, published in 2011.[95]

The novel was also serialised in the April, May and June 1964 issues of Playboy magazine, with illustrations from Daniel Schwartz.[96][97] In the January 1997 edition of Playboy, the short story "Blast from the Past" appeared. Written by Raymond Benson, the story depicts the murder of James Suzuki—the child Bond fathered with Kissy Suzuki. Bond finds out that his son had been murdered by Irma Bunt as revenge for the death of Blofeld. Bond tracks her down and kills her.[98]

In 1967 the book was adapted into the fifth film in the Eon Productions series. It stars Sean Connery as Bond, and the screenplay was by Fleming's friend Roald Dahl.[99][100] Only a few elements of the novel and a limited number of Fleming's characters survive into the film version, which has a heavy focus on Bond's gadgets.[101][102] The June 1967 issue of Playboy contained the feature "007's Oriental Eyefuls". This was a six-page pictorial that featured several of the women from the film, which included Mie Hama (who played Kissy Suzuki) and Akiko Wakabayashi (who played Aki),[j] as well as some of the film's extras. The accompanying text was written by Dahl.[104]

In 1990 the novel was adapted into a 90-minute radio play for BBC Radio 4 with Michael Jayston playing James Bond. The production was repeated a number of times between 2008 and 2013.[105] In 2021 elements of You Only Live Twice were used in No Time to Die, the twenty-sixth film in the Eon Productions series, which stars Daniel Craig as Bond. The film included Bond mourning the loss of his romantic partner and eventually seeking revenge by strangling the main villain and destroying his "garden of death" on a private island between Russia and Japan.[106][107][108]

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ a b The books were Casino Royale (1953), Live and Let Die (1954), Moonraker (1955), Diamonds Are Forever (1956), From Russia, with Love (1957), Dr. No (1958), Goldfinger (1959), Thunderball (1961), The Spy Who Loved Me (1962) and the short story collection For Your Eyes Only (1960).[2]

- ^ You Only Live Twice continues the story from On Her Majesty's Secret Service (published in 1963) which ended with the murder of Bond's wife by Ernst Stavro Blofeld and Irma Bunt.[1]

- ^ The presence of the royal arms meant that The Times could not give permission without first receiving clearance from the royal family.[8]

- ^ Tom Blofeld's son is Henry Blofeld, a sports journalist, who was a cricket commentator for Test Match Special on BBC Radio.[25]

- ^ Hughes was also the model for "Old Craw" in John le Carré's The Honourable Schoolboy.[18]

- ^ Hatcher went on to observe that "Like many another western writer before and since, Fleming felt compelled to explain Japan in a way that he had never explained previous unfamiliar locations in his novels, as if it were less a country to be experienced than a set of nested paradoxes to be decoded."[49]

- ^ Panek gives as an example the plot of Casino Royale, in which the three events are the game of baccarat, Vesper Lynd's kidnapping and the love story between Lynd and Bond.[51]

- ^ Other novels in the series to use the same motif are Moonraker, From Russia, with Love, Goldfinger and The Spy Who Loved Me.[63]

- ^ A guinea was originally a gold coin whose value was fixed at twenty-one shillings (£1.05). By this date the coin was obsolete and the term simply functioned as a label for that sum.[79] According to calculations based on the Consumer Price Index measure of inflation, 300 guineas in 1964 is approximately £8,060 in 2023, while 250 guineas is £6,720, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[80]

- ^ Aki was a character created for the film who does not appear in the novel.[103]

References

- ^ Benson 1988, p. 134.

- ^ a b "Ian Fleming's James Bond Titles". Ian Fleming Publications.

- ^ a b c d e f Benson 1988, p. 24.

- ^ a b Parker 2014, p. 294.

- ^ Fleming 2009, p. 320.

- ^ Fleming 2015, p. 346.

- ^ Pearson 1967, p. 402.

- ^ a b Lycett 1996, pp. 420–421.

- ^ a b c d Benson 1988, p. 136.

- ^ "Obituary: Mr. Ian Fleming". The Times.

- ^ a b c Chancellor 2005, p. 222.

- ^ a b c Black 2005, p. 60.

- ^ a b c Black 2005, p. 61.

- ^ Griswold 2006, p. 11.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 75.

- ^ Macintyre 2008, p. 205.

- ^ a b c d Chancellor 2005, pp. 222–223.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 58.

- ^ Macintyre 2008, p. 33.

- ^ "Affairs of the Heart". Ian Fleming Publications.

- ^ a b c d e Chancellor 2005, p. 113.

- ^ Marti & Wälty 2012.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, p. 117.

- ^ Macintyre 2008a, p. 36.

- ^ Thomas 2020, pp. 111–112.

- ^ Dresner 2016, p. 628.

- ^ a b c Panek 1981, p. 204.

- ^ Hatcher 2007, p. 225.

- ^ Hatcher 2007, p. 222.

- ^ Hatcher 2007, pp. 222, 225–226.

- ^ Fleming 1964a, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b c d Benson 1988, p. 138.

- ^ a b c Benson 1988, p. 137.

- ^ Fleming 1965, p. 25.

- ^ Benson 1988, pp. 138–139.

- ^ Amis 1966, p. 36.

- ^ Amis 1966, p. 42.

- ^ Benson 1988, p. 139.

- ^ Fleming 1965, p. 61.

- ^ Eco 2009, p. 42.

- ^ Lindner 2009, p. 79.

- ^ Panek 1981, p. 213.

- ^ Halloran 2005, p. 168.

- ^ Bennett & Woollacott 1987, p. 124.

- ^ Eco 2009, p. 39.

- ^ Panek 1981, p. 217.

- ^ a b Druce 1992, p. 156.

- ^ a b Hatcher 2007, pp. 227–228.

- ^ Hatcher 2007, p. 228.

- ^ a b Panek 1981, p. 212.

- ^ Clive 2017.

- ^ a b c Black 2005, p. 62.

- ^ Biddulph 2009, p. 132.

- ^ Bennett & Woollacott 1987, pp. 124–125.

- ^ Macintyre 2008, p. 113.

- ^ Chancellor 2005, pp. 200–201.

- ^ Macintyre 2008, p. 187.

- ^ Druce 1992, p. 175.

- ^ Fleming 1965, p. 101.

- ^ Druce 1992, p. 176.

- ^ Bennett & Woollacott 1987, p. 256.

- ^ Ladenson 2003, p. 230; Benson 1988, pp. 129, 231; Sternberg 1983, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Panek 1981, p. 214; Benson 1988, p. 136; Fleming 1965, p. 78.

- ^ Fleming 1965, p. 119.

- ^ Druce 1992, p. 155.

- ^ Fleming 1965, p. 65.

- ^ Fleming 1965, p. 172.

- ^ Fleming 1965, p. 180.

- ^ a b c d Benson 1988, p. 26.

- ^ a b Fleming 1964b, p. 6.

- ^ a b c d "New Fiction". The Times.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 437.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 419.

- ^ Turner 2016, 3687.

- ^ Turner 2016, 3690.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 426.

- ^ Lycett 1996, p. 390.

- ^ Besly 1997, p. 25.

- ^ Clark 2023.

- ^ a b Poore 1964, p. 19.

- ^ Hines 2018, p. 37.

- ^ Bennett & Woollacott 2009, p. 17.

- ^ Gilbert 2012, p. 363.

- ^ "You Only Live Twice". WorldCat.

- ^ Simpson 2023.

- ^ Nugent & Harrison 2023.

- ^ Iles 1964, p. 8.

- ^ a b Duval Smith 1964, p. 28.

- ^ Ross 1964, p. 529.

- ^ a b Richardson 1964, p. 27.

- ^ a b c d e Chancellor 2005, p. 223.

- ^ Castle 1964, p. 43.

- ^ a b Fleming, Gammidge & McLusky 1988, p. 6.

- ^ McLusky et al. 2011, p. 76.

- ^ Lindner 2009, p. 92.

- ^ Hines 2018, pp. 37, 55.

- ^ Hines 2018, p. 185.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 81.

- ^ Collin 2021.

- ^ Barnes & Hearn 2001, p. 72.

- ^ Hines 2018, p. 56.

- ^ Rubin 2003, p. 8.

- ^ Hines 2018, p. 168.

- ^ James Bond – You Only Live Twice". BBC Radio 4 Extra.

- ^ Schilling 2021.

- ^ Crow 2021.

- ^ Hegarty 2021.

Sources

Books

- Amis, Kingsley (1966). The James Bond Dossier. London: Pan Books. OCLC 154139618.

- Barnes, Alan; Hearn, Marcus (2001). Kiss Kiss Bang! Bang!: the Unofficial James Bond Film Companion. Batsford Books. ISBN 978-0-7134-8182-2.

- Bennett, Tony; Woollacott, Janet (1987). Bond and Beyond: The Political Career of a Popular Hero. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-4160-1361-0.

- Bennett, Tony; Woollacott, Janet (2009). "The Moments of Bond". In Lindner, Christoph (ed.). The James Bond Phenomenon: A Critical Reader. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Benson, Raymond (1988). The James Bond Bedside Companion. London: Boxtree Ltd. ISBN 978-1-8528-3233-9.

- Besly, Edward (1997). Loose Change: A Guide to Common Coins and Medals. Cardiff: National Museum Wales. ISBN 978-0-7200-0444-1.

- Black, Jeremy (2005). The Politics of James Bond: from Fleming's Novel to the Big Screen. University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-6240-9.

- Chancellor, Henry (2005). James Bond: The Man and His World. London: John Murray. ISBN 978-0-7195-6815-2.

- Druce, Robert (1992). This Day our Daily Fictions: An Enquiry into the Multi-million Bestseller Status of Enid Blyton and Ian Fleming. Amsterdam: Rodopi. ISBN 978-90-5183-401-7.

- Eco, Umberto (2009). "The Narrative Structure of Ian Fleming". In Lindner, Christoph (ed.). The James Bond Phenomenon: A Critical Reader. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Fleming, Fergus (2015). The Man with the Golden Typewriter: Ian Fleming's James Bond Letters. New York: Bloomsbury. ISBN 978-1-6328-6489-5.

- Fleming, Ian (1964a). Thrilling Cities. London: The Reprint Society. OCLC 3260418.

- Fleming, Ian (1965). You Only Live Twice. London: Pan Books. OCLC 499133531.

- Fleming, Ian; Gammidge, Henry; McLusky, John (1988). Octopussy. London: Titan Books. ISBN 1-8528-6040-5.

- Fleming, Ian (2009). "Ian Fleming on Writing Thrillers". Devil May Care. By Faulks, Sebastian. London: Penguin Books. pp. 314–321. ISBN 978-0-1410-3545-1.

- Gilbert, Jon (2012). Ian Fleming: The Bibliography. London: Queen Anne Press. ISBN 978-0-9558-1897-4.

- Griswold, John (2006). Ian Fleming's James Bond: Annotations and Chronologies for Ian Fleming's Bond Stories. Bloomington, Indiana: AuthorHouse. ISBN 978-1-4259-3100-1.

- Halloran, Vivian (2005). "Tropical Bond". In Comentale, Edward P.; Watt, Stephen; Willman, Skip (eds.). Ian Fleming and James Bond: The Cultural Politics of 007. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 158–177. ISBN 978-0-2533-4523-3.

- Hatcher, John (2007). "Ian Fleming (1908–64), Novelist and Journalist". In Cortazzi, Hugh (ed.). Britain & Japan: Biographical Portraits. Folkestone, Kent: Global Oriental. pp. 221–233. ISBN 978-1-9052-4633-5.

- Hines, Claire (2018). The Playboy and James Bond: 007, Ian Fleming and Playboy Magazine. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-8226-9.

- Ladenson, Elisabeth (2003). "Pussy Galore". In Lindner, Christoph (ed.). The James Bond Phenomenon: a Critical Reader. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Lindner, Christoph (2009). The James Bond Phenomenon: a Critical Reader. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-6541-5.

- Lycett, Andrew (1996). Ian Fleming. London: Phoenix. ISBN 978-1-8579-9783-5.

- Macintyre, Ben (2008). For Your Eyes Only. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7475-9527-4.

- McLusky, John; Gammidge, Henry; Lawrence, Jim; Fleming, Ian; Horak, Yaroslav (2011). The James Bond Omnibus Vol. 2. London: Titan Books. ISBN 978-1-8485-6432-9.

- Panek, LeRoy (1981). The Special Branch: The British Spy Novel, 1890–1980. Bowling Green, Ohio: Bowling Green University Popular Press. ISBN 978-0-8797-2178-7.

- Parker, Matthew (2014). Goldeneye. London: Hutchinson. ISBN 978-0-0919-5410-9.

- Pearson, John (1967). The Life of Ian Fleming: Creator of James Bond. London: Pan Books. OCLC 669702874.

- Rubin, Steven Jay (2003). The Complete James Bond Movie Encyclopaedia. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-0714-1246-9.

- Thomas, Graham (2020). The Definitive Story of You Only Live Twice: Fleming, Bond and Connery in Japan. London: Sagus. ISBN 978-1-9114-8998-6.

- Turner, Jon Lys (2016). The Visitors' Book: In Francis Bacon's Shadow: The Lives of Richard Chopping and Denis Wirth-Miller (Kindle ed.). London: Constable. ISBN 978-1-4721-2168-4.

Journals and magazines

- Biddulph, Edward (June 2009). "'Bond Was Not a Gourmet': An Archaeology of James Bond's Diet". Food, Culture & Society. 12 (2): 131–149. doi:10.2752/155280109X368688. ISSN 1552-8014.

- Dresner, Lisa M. (June 2016). ""Barbary Apes Wrecking a Boudoir": Reaffirmations of and Challenges to Western Masculinity in Ian Fleming's Japan Narratives". The Journal of Popular Culture. 49 (3): 627–645. doi:10.1111/jpcu.12422. ISSN 0022-3840.

- Marti, Michael; Wälty, Peter (7 October 2012). "Und das ist die Mama von James Bond". Der Spiegel (in German). Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Ross, Maggie (26 March 1964). "New Novels". The Listener. p. 529.

- Sternberg, Meir (1983). "Knight Meets Dragon in the James Bond Saga: Realism and Reality-Models". Style. 17 (2): 142–180. JSTOR 42945465.

News

- Castle, Mary (6 September 1964). "Thrills and Chills Dept". The Boston Globe. p. 43.

- Collin, Robbie (18 February 2021). "'Sean Connery? He Never Stood Anyone a Round': Roald Dahl's Love-Hate Relationship with Hollywood". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 10 April 2021.

- Duval Smith, Peter (26 March 1964). "Could Do Better". The Financial Times. p. 28.

- Fleming, Ian (2 March 1964b). "James Bond: You Only Live Twice". Daily Express. p. 6.

- Iles, Francis (17 April 1964). "Criminal Records". The Guardian. p. 8.

- Macintyre, Ben (5 April 2008a). "Bond – the Real Bond". The Times. p. 36.

- Nugent, Annabel; Harrison, Ellie (27 February 2023). "'Sweet Tang of Rape': Offensive Language that has—and hasn't—Been Cut from Ian Fleming's James Bond Books". The Independent.

- "New Fiction". The Times. 19 March 1964. p. 16.

- "Obituary: Mr. Ian Fleming". The Times. 13 August 1964. p. 12.

- Poore, Charles (22 August 1964). "Books of the Times". The New York Times. p. 19.

- Richardson, Maurice (15 March 1964). "Bondo-san and Tiger Tanaka". The Observer. p. 27.

- Simpson, Craig (25 February 2023). "James Bond Books Edited to Remove Racist References". The Sunday Telegraph.

Websites

- "Affairs of the Heart". Ian Fleming Publications. 12 September 2016. Retrieved 12 July 2021.

- Clark, Gregory (2023). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Archived from the original on 1 April 2023. Retrieved 22 February 2023.

- Clive, Nigel (2017). "Philby, Harold Adrian Russell (Kim) (1912–1988)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/40699. Retrieved 25 October 2011. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Crow, David (6 December 2021). "No Time to Die Is the Best You Only Live Twice Adaptation". Den of Geek. Retrieved 6 December 2021.

- Hegarty, Tasha (12 December 2021). "Why No Time to Die linked back to classic James Bond movie". Digital Spy. Retrieved 12 December 2021.

- "Ian Fleming's James Bond Titles". Ian Fleming Publications. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 7 August 2015.

- "James Bond – You Only Live Twice". BBC Radio 4 Extra. BBC. Retrieved 29 September 2013.

- Schilling, Dave (11 October 2021). "No Time to Die ends Daniel Craig's Bond run with an act of fate". Polygon. Retrieved 11 October 2021.

- "You Only Live Twice". WorldCat. Retrieved 11 July 2024.

External links

Quotations related to You Only Live Twice at Wikiquote

Quotations related to You Only Live Twice at Wikiquote- You Only Live Twice at Faded Page (Canada)

- Official Website of Ian Fleming Publications