Vagina

| Vagina | |

|---|---|

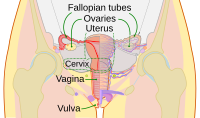

Diagram of the female human reproductive tract and ovaries | |

Vulva with pubic hair removed and labia spread to show the opening of the vagina:

| |

| Details | |

| Precursor | urogenital sinus and paramesonephric ducts |

| Artery | superior part to uterine artery, middle and inferior parts to vaginal artery |

| Vein | uterovaginal venous plexus, vaginal vein |

| Nerve |

|

| Lymph | upper part to internal iliac lymph nodes, lower part to superficial inguinal lymph nodes |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Vagina |

| MeSH | D014621 |

| TA | A09.1.04.001 |

| FMA | 19949 |

| Anatomical terminology | |

The vagina is a part of the female body. It is between the perineum and the urethra. The vaginal opening is much larger than the urethral opening. It is a tube leading from the uterus to the outside of the body. Menstrual fluid (red, blood-filled liquid lost during menstruation) leaves the body through the vagina. During sexual intercourse, the penis is put into the vagina. During birth, the vagina opens to let the baby come out from the uterus. The vagina is reddish-pink in color, though colors may vary.

Development

Between the ages of 9-15 years, the vagina and uterus get bigger. The uterus is the organ in which a baby grows. The external opening of the vagina leading to the vulva, between the legs. A clear or whitish fluid may start to flow out of the vagina to keep it clean.[1]

Location

The opening to the vagina is located behind the urethral opening and in front of the perineum. The vagina is the tube leading from the uterus to the outside of the body. The opening is between the legs, inside the labium, behind the opening to the urethra, and in front of the anus.

Anatomy

The vagina is an elastic, muscular tube. It starts at the cervix and ends at the vulva.[2] It is about 6 to 7.5 centimetres (2.4 to 3.0 in) wide, and 9 centimetres (3.5 in) long.[3] During sexual intercourse and childbirth, the vagina gets wider and bigger.[4] It has to be lubricated to stay clean and allow sexual intercourse and childbirth. It is lubricated partially by the Bartholin's glands. This lubrication also allows sperm easier access to fertilize an ovum.

The vaginal biome

Like many tissues, the vagina has a natural biome, a flora and fauna of microscopic organisms. The vagina is an interface between the host and the environment. Its surface is covered by a protective epithelium where bacteria and other microorganisms grow. The ectocervix (that's the vaginal part of the cervix) is not sterile.[5]

Functions

Release

The vagina releases blood and tissue during menstruation. Tampons or other products can be used to absorb some of the blood.[6]

Sexual activity

When a woman is aroused, she has pleasurable feelings in her genital region. The vagina gets up to 8.5 centimetres (3.3 in) wide. It can get bigger with more stimulation.[7] During sexual intercourse, the man's penis is placed in the woman's vagina. The vagina is warm and soft, and it places pressure on the man's penis. That can feel good for both partners and usually makes the man have an orgasm after repeated thrusts. For orgasm in women, the vagina has significantly fewer nerve endings than the clitoris, and therefore rubbing or applying other consistent pressure against the clitoris is usually needed to help the woman have an orgasm.[8][9] During the man's orgasm, he ejaculates semen from his penis into the vagina. The semen contains sperm. The sperm can move from the vagina into the uterus to fertilize an egg and make a woman pregnant.

The G-spot may be a highly sensitive area near the entrance inside of the human vagina.[10] If stimulated, it leads to a strong orgasm or female ejaculation in some women.[11][12][13] Some doctors and researchers who specialize in the anatomy of women believe that the G-spot does not exist, and that if it does exist, it is an extension of the clitoris.[14][15][16][17]

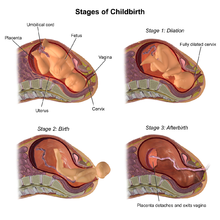

Childbirth

During birth, the vagina acts as a pathway for the baby to leave the mother's body. The vagina is very elastic and stretches to many times its normal diameter during birth.

Pregnancy

Sperm needs to be deposited at the top of the vagina near the cervix and fertilize the ovum (egg) if pregnancy is to occur. In a normal childbirth, babies come out through the vagina.

Related pages

References

- ↑ Marshall, Human Growth, p. 187.

- ↑ http://www.womenshealth.gov/glossary/#vagina Womenshealth.gov

- ↑ Gray's Anatomy

- ↑ "The sexual response cycle". EngenderHealth. Archived from the original on 2007-10-30. Retrieved 2007-10-13.

- ↑ 'sterile' here means having no biome on the surface.

- ↑ "All about Menstruation". Retrieved 2010-05-14.

- ↑ "Does size matter". TheSite.org. Archived from the original on 2007-02-21. Retrieved 2006-08-12.

- ↑ Psychology Applied to Modern Life: Adjustment in the 21st Century. Cengage Learning. 2011. p. 386. ISBN 978-1-111-18663-0. Retrieved November 14, 2012.

{cite book}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ↑ Sex and Society, Volume 2. Marshall Cavendish Corporation. 2009. pp. 960 pages. ISBN 978-0761479079. Retrieved November 14, 2012.

{cite book}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) - ↑ Darling, CA; Davidson, JK; Conway-Welch, C. (1990). "Female ejaculation: perceived origins, the Grafenberg spot/area, and sexual responsiveness". Arch Sex Behav. 19 (1): 29–47. doi:10.1007/BF01541824. ISSN 0004-0002. PMID 2327894. S2CID 25428390.

{cite journal}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Crooks, R; Baur, K (1999). Our Sexuality. California: Brooks/Cole. ISBN 9780534354671.

- ↑ Jannini E, Simonelli C, Lenzi A (2002). "Sexological approach to ejaculatory dysfunction". Int J Androl. 25 (6): 317–23. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2605.2002.00371.x. PMID 12406363. S2CID 85033696.

{cite journal}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Jannini E, Simonelli C, Lenzi A (2002). "Disorders of ejaculation". J Endocrinol Invest. 25 (11): 1006–19. doi:10.1007/BF03344077. PMID 12553564. S2CID 9852872.

{cite journal}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Hines, T (August 2001). "The G-Spot: A modern gynecologic myth". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 185 (2): 359–62. doi:10.1067/mob.2001.115995. PMID 11518892.

- ↑ O'Connell HE, Sanjeevan KV, Hutson JM (October 2005). "Anatomy of the clitoris". The Journal of Urology. 174 (4 Pt 1): 1189–95. doi:10.1097/01.ju.0000173639.38898.cd. PMID 16145367. S2CID 26109805.

{cite journal}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) "Time for rethink on the clitoris". BBC News. 11 June 2006. - ↑ "Is the Female G-Spot Truly a Distinct Anatomic Entity?". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2011 (3): 719–726. January 2012. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2011.02623.x. PMID 22240236.

{cite journal}: Unknown parameter|authors=ignored (help) "G-Spot Does Not Exist, 'Without A Doubt,' Say Researchers". Huffington Post. January 19, 2012. - ↑ Alexander, Brian (January 18, 2012). "Does the G-spot really exist? Scientists can't find it". MSNBC.com. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved March 2, 2012.

Other websites

- Pink Parts Archived 2008-10-22 at the Wayback Machine - More information on female sexual anatomy.