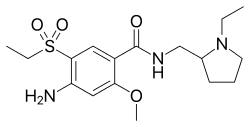

氨磺必利

| |

| |

| 臨床資料 | |

|---|---|

| 商品名 | Solian(首利安), others |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | 国际药品名称 |

| 懷孕分級 |

|

| 给药途径 | By mouth, intravenous |

| ATC碼 | |

| 法律規範狀態 | |

| 法律規範 |

|

| 藥物動力學數據 | |

| 生物利用度 | 48%[1][2] |

| 血漿蛋白結合率 | 16%[2] |

| 药物代谢 | Hepatic (minimal; most excreted unchanged)[2] |

| 生物半衰期 | 12 hours[1] |

| 排泄途徑 | Renal[1] (23–46%),[3][4]Faecal[2] |

| 识别信息 | |

| |

| CAS号 | 71675-85-9 |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.068.916 |

| 化学信息 | |

| 化学式 | C17H27N3O4S |

| 摩尔质量 | 369.48 g/mol |

| 3D模型(JSmol) | |

| |

| |

氨磺必利(INN:amisulpride),又译阿米舒必利,它是一种治疗精神分裂症的抗精神病药。在意大利,它也被以每天50mg的剂量来治疗心境恶劣。[5]通常地,它被归为第二代抗精神病药,就是所谓的非典型抗精神病药。化学上来说,它属于苯甲酰胺类的,同其它的苯甲酰胺类抗精神病药(例如舒必利)相似,它有可能会提高泌乳素的分泌的水平并升高血清泌乳素的量,从而导致没有月經週期、乳房增大(甚至对于男性而言也会这样)、在没有哺乳的情况下泌乳、生育力受损、勃起功能障碍和乳房疼痛等,而且在很低的概率下,它会像典型抗精神病药一样引起运动障碍。[6][7][8]同典型抗精神病药相比,它对与精神分裂的疗效稍微好一些。[7]

同多数其他的被批准的抗精神病药一样,氨磺必利被认为是通过减少多巴胺D2受体的信号传导而起作用的。对于氨磺必利而言,这是通过阻断或拮抗受体而做到的。氨磺必利治疗心境恶劣和精神分裂的阴性症状的功效据信是由于它阻断了突触前D2受体,使多巴胺脱抑制性释放,升高浓度的多巴胺作用于D1受体,从而缓解心境恶劣以及精神分裂的阴性症状。[5]

它由Sanofi-Avents在1990年代推向市场。它的专利已于2008年过期,因此现在有了通用名药物。它在除了加拿大和美国之外的所有英语国家出售。

医学用途

精神分裂

2013年,一项研究比较了15种抗精神病药在治疗精神分裂方面的疗效,氨磺必利表现出了相当高的效力并排名第二。疗效比排名第三的奥氮平高11%,比氟哌啶醇、喹硫平和阿立哌唑高32-35%,比排名第一的氯氮平低25%。[7]但是有一些研究指出在治疗精神分裂方面,氨磺必利的疗效与奥氮平相近。[9][10]就像联用舒必利那样联用氨磺必利来治疗氯氮平抵抗的难治性患者被认为是一种行之有效的选择。(虽然这种观点所基于的证据质量较低)[11][12]最近,另一项研究表明氨磺必利是用于急性精神分裂的合理的一线选择。[13]

心境恶劣与抑郁症

有研究在有心境恶劣障碍的病患中在有安慰剂的情况下将氨磺必利与氟西汀、丙咪嗪、阿米替林和阿米庚酸相比较,临床观察显示氨磺必利可能有抗抑郁活性。[14]

以标准的抑郁评级为依据,在单独患有心境恶劣障碍的患者中,50mg/d的氨磺必利同25-75mg/d的阿米替林[15]和20mg/d的氟西汀[16]一样有效。两项安慰剂控制的实验在患有原发性心境恶劣和抑郁症的患者中,将氨磺必利与阿米庚酸(200mg/d)[17]和丙咪嗪(100mg/d)[18]相比较,结果显示氨磺必利同这些抗抑郁药同样有效。

氨磺必利可用于加速SSRI的生效,一项针对汉密尔顿抑郁量表(HDRS)评分超过20的36岁以上(平均51.3岁)的女性患者的研究,在使用100mg/d的氟伏沙明的基础上增加50mg/d的氨磺必利,结果显示在第一周时,平均HDRS得分就与基线有显著差异(p=0.003)。[19]

抑郁症引发的焦虑

一项持续一年的研究将患者分为分别使用50mg/d的氨磺必利和10mg/d的艾斯西酞普兰的两组,实验进行到第十五周时,两组的HAMA分值与基线相比皆有显著差异,两组之间没有统计学差异,证明氨磺必利和艾斯西酞普兰同为治疗抑郁症引发的焦虑的有效药物。[20]

禁忌症

在如下的情况下使用氨磺必利是禁忌的:

同时也不建议在对氨磺必利或其药剂的任何一种辅料过敏的人群中使用氨磺必利。

不良反应

很常见(发病率≥10%)[21]

- 锥体外系副作用(EPS;包括肌张力障碍、震颤、静坐不能、帕金森氏症),氨磺必利会造成中等程度的EPS,效力高于阿立哌唑、氯氮平、伊潘立酮、奥氮平、喹硫平和舍吲哚;低于氯丙嗪、氟哌啶醇、鲁拉西酮、帕利哌酮、利培酮、齐拉西酮和佐替平。

- 唾液分泌过多

- 肺热

- 高催乳素血症(可导致乳糜泻、乳房增大和压痛、性功能障碍等),高催乳素血症是由位于脑下垂体前叶中的催乳素细胞上的D2受体被拮抗作用引起的。由于氨磺必利穿过血脑屏障的能力较差,拮抗外周D2受体的效力与中枢D2受体的比值较大,这意味着如果要达到治疗效果(中枢D2受体被拮抗约60-80%[26]),外周的氨磺必利浓度需要足够大,包括脑下垂体前叶中的D2受体便被大量拮抗,因此它有着较高的提升血清催乳素水平的倾向。[27][28]

- 体重增加,增加的重量比氯丙嗪、氯氮平,伊潘立酮、奥氮平、帕利哌酮、喹硫平、利培酮、舍吲哚、佐替平更少,比氟哌啶醇、鲁拉西酮、齐拉西酮、阿立哌唑和阿塞那平更多。(虽然没有统计学意义)[7]

- 癫痫发作

- 眼动危象

- QT间期延长(在最近的一项对15种抗精神病药的安全性和有效性的荟萃分析中,发现氨磺必利对QT期延长的效应高居第二位。)

药物过量

尖端扭转型室性心动过速(Torsades de pointes,TdP)在过量服用中很常见,[29][30]氨磺必利过量造成中等危险程度的TdP(TCA造成高度危险的TdP,而SSRI只造成轻微的危险)。[31][32]

药物相互作用

氨磺必利不应同延长QT间期的药物(例如西酞普兰、文拉法辛、安非他酮、氯氮平、TCA、舍吲哚和齐拉西酮等)[31];降低心率的药物以及可诱发低钾血症的药物一同使用。同样地,由于引发迟发性运动障碍和神经阻滞剂恶性综合征的风险,氨磺必利与其他的抗精神病药的联用是不明智的。[31]

药理学

药效学

| 位点 | Ki(nM) | 物种 | 引用 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5-HT1A | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| 5-HT1B | 1,744 | 人类 | [34] |

| 5-HT1E | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| 5-HT2A | 8,304 | 人类 | [34] |

| 5-HT2B | 13 | 人类 | [34] |

| 5-HT2C | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| 5-HT3 | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| 5-HT5A | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| 5-HT6 | 4,154 | 人类 | [34] |

| 5-HT7 | 11.5 | 人类 | [34] |

| α1A | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| α1B | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| α1D | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| α2A | 1,114 | 人类 | [34] |

| α2C | 1,540 | 人类 | [34] |

| β1 | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| β2 | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| β3 | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| D1 | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| D2 | 3.0 | 人类 | [34] |

| D3 | 3.5 | 大鼠 | [34] |

| D4 | 2,369 | 人类 | [34] |

| D5 | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| H1 | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| H2 | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| H4 | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| M1 | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| M2 | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| M3 | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| M4 | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| M5 | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| σ1 | >10,000 | 大鼠 | [34] |

| σ2 | >10,000 | 大鼠 | [34] |

| MOR | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| DOR | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| KOR | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| GHBHigh | 50 (IC50) | 大鼠 | [35] |

| NMDA(PCP) | >10,000 | 大鼠 | [36] |

| SERT | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| NET | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| DAT | >10,000 | 人类 | [34] |

| 数值为Ki(nM)。数值越小,药物对此位点的结合越强 | |||

氨磺必利主要作为D2和D3受体的拮抗剂而起作用。它对这些受体有高亲和力,解离常数(Ki)分别为3.0和3.5nM。虽然在用于治疗精神分裂症的剂量下它会抑制多巴胺能的传递,但是在低剂量下它会优先阻滞突触前多巴胺自身受体,导致多巴胺脱抑制性释放,增加多巴胺能,因此,低剂量氨磺必利也被用于治疗心境恶劣和抑郁症。[22][37]

在治疗浓度下(对氨磺必利而言IC50=50nM),氨磺必利和它的近亲舒必利、左旋舒必利和舒托必利都显示出了与GHB受体的高亲和力的结合[35]

氨磺必利、舒托必利和舒必利在试管中对D2受体(IC50分别为27、120和181nM)和D3受体(IC50分别为3.6、4.8和17.5)的亲和力依次降低。[38]

虽然长期以来人们普遍认为对多巴胺能的调节是氨磺必利抗抑郁和抗精神病的唯一原因,但随后发现它也是5-羟色胺5-HT7受体的有效的拮抗剂(Ki=11.5nM)。[34]几种其他的非典型抗精神病药,例如利培酮和齐拉西酮,也是5-HT7受体的有效的拮抗剂,而且选择性地拮抗5-HT7受体本身也显示出了抗抑郁效果。一项实验制备了5-HT7受体敲除的小鼠,以表明5-HT7受体在氨磺必利的抗抑郁作用中的角色。[34]该研究发现,在两种广泛使用的啮齿动物抑郁症模型中,即在尾部悬吊试验和强迫游泳试验中,这些小鼠在用氨磺必利治疗后没有表现出抗抑郁反应。[34]表明氨磺必利的抗抑郁效应是由5-HT7受体介导的。[34]

氨磺必利似乎也以高亲和力与5-HT2B受体结合(Ki=13nM),充当一种拮抗剂。[34]这一点的临床意义(如果有的话)尚不清楚。[34]无论如何,没有证据表明这种作用可以介导氨磺必利的任何治疗作用。[34]

社会与文化

商品名

商品名包括:Amazeo、Amipride (澳大利亚)、Amival、Solian (澳大利亚,爱尔兰,俄罗斯,英国,南非)、Soltus、Sulpitac (印度)、Sulprix (澳大利亚)、Midora(罗马尼亚)和Socian (巴西)。

可用性

在中国,氨磺必利被批准用于治疗精神分裂症,氨磺必利在美国未被FDA批准,但在欧洲(法国、德国、意大利、瑞士、俄罗斯、英国等);以色列;墨西哥;印度;新西兰和澳大利亚(TGA于2002年2月批准)被批准治疗思觉失调和精神分裂症。[39][40]

參考文獻

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Rosenzweig, P.; Canal, M.; Patat, A.; Bergougnan, L.; Zieleniuk, I.; Bianchetti, G. A review of the pharmacokinetics, tolerability and pharmacodynamics of amisulpride in healthy volunteers. Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental. 2002-01, 17 (1): 1–13 [2021-10-06]. ISSN 0885-6222. PMID 12404702. doi:10.1002/hup.320. (原始内容存档于2021-10-06) (英语).

- ^ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 PRODUCT INFORMATION SOLIAN® TABLETS and SOLUTION (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd. 9 September 2013 [17 October 2013]. (原始内容存档于2019-12-31).

- ^ Caccia, S. Biotransformation of Post-Clozapine Antipsychotics Pharmacological Implications. Clinical Pharmacokinetics. May 2000, 38 (5): 393–414. PMID 10843459. doi:10.2165/00003088-200038050-00002.

- ^ Noble, Stuart; Benfield, Paul. Amisulpride: A Review of its Clinical Potential in Dysthymia. CNS Drugs. 1999, 12 (6): 471–483. ISSN 1172-7047. doi:10.2165/00023210-199912060-00005 (英语).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 Pani, L; Gessa, G L. The substituted benzamides and their clinical potential on dysthymia and on the negative symptoms of schizophrenia. Molecular Psychiatry. 2002-03, 7 (3): 247–253 [2021-10-06]. ISSN 1359-4184. PMID 11920152. doi:10.1038/sj.mp.4001040. (原始内容存档于2021-12-27) (英语).

- ^ Pharmaceutical Society of Australia. Australian medicines handbook.. Adelaide, S. Aust.: Australian Medicines Handbook. 2013 [2021-10-06]. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3. OCLC 826673635. (原始内容存档于2021-10-06).

- ^ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Leucht, Stefan; Cipriani, Andrea; Spineli, Loukia; Mavridis, Dimitris; Örey, Deniz; Richter, Franziska; Samara, Myrto; Barbui, Corrado; Engel, Rolf R. Comparative efficacy and tolerability of 15 antipsychotic drugs in schizophrenia: a multiple-treatments meta-analysis. The Lancet. 2013-09-14, 382 (9896): 951–962 [2021-10-06]. ISSN 0140-6736. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60733-3. (原始内容存档于2014-10-23) (英语).

- ^ Brayfield, A, ed. (June 2017). "Amisulpride: Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). MedicineComplete. Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 5 August 2017.

- ^ Komossa, K; Rummel-Kluge, C; Hunger, H; Schmid, F; Schwarz, S; Silveira da Mota Neto, JI; Kissling, W; Leucht, S (January 2010). "Amisulpride versus other atypical antipsychotics for schizophrenia" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1): CD006624. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006624.pub2. PMC 4164462 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). PMID 20091599 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Leucht, S; Corves, C; Arbter, D; Engel, RR; Li, C; Davis, JM (January 2009). "Second-generation versus first-generation antipsychotic drugs for schizophrenia: a meta-analysis". Lancet. 373 (9657): 31–41. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61764-X. PMID 19058842 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Solanki, RK; Sing, P; Munshi, D (Oct–Dec 2009). "Current perspectives in the treatment of resistant schizophrenia". Indian Journal of Psychiatry. 51 (4): 254–60. doi:10.4103/0019-5545.58289. PMC 2802371. PMID 20048449 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Mouaffak, F; Tranulis, C; Gourevitch, R; Poirier, MF; Douki, S; Olié, JP; Lôo, H; Gourion, D (2006). "Augmentation Strategies of Clozapine With Antipsychotics in the Treatment of Ultraresistant Schizophrenia". Clinical Neuropharmacology. 29 (1): 28–33. doi:10.1097/00002826-200601000-00009. PMID 16518132 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Nuss, P.; Hummer, M.; Tessier, C. (2007). "The use of amisulpride in the treatment of acute psychosis" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). Therapeutics and Clinical Risk Management. 3 (1): 3–11. doi:10.2147/tcrm.2007.3.1.3. PMC 1936283 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). PMID 18360610 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Vishal Chhabra, Manjeet Singh Bhatia. "Amisulpride: a Brief Review" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)(PDF) DELHI PSYCHIATRY JOURNAL Vol.10 No.2. OCTOBER 2007

- ^ Ravizza L. "Amisulpride in medium-term treatment of dysthymia: a six-month, double-blind safety study versus amitriptyline. AMILONG investigators" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). Journal of Psychopharmacology. 13(3):248-54 · February 1999. PMID: 10512080 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Smeraldi, E. "Amisulpride versus fluoxetine in patients with dysthymia or major depression in partial remission: a double-blind, comparative study" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). Journal of Affective Disorders, Volume 48, Issue 1, 1998, Pages 47-56, ISSN 0165-0327 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Boyer P, Lecrubier Y, Stalla-Bourdillon A, Fleurot O: Amisulpride versus Amineptine and Placebo for the Treatment of Dysthymia (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). Neuropsychobiology 1999;39:25-32. doi: 10.1159/000026556 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆)

- ^ Lecrubier, Y; Boyer, P; Turjanski, S; Rein, W. Amisulpride versus imipramine and placebo in dysthymia and major depression. Journal of Affective Disorders. 1997-04, 43 (2): 95–103 [2018-10-24]. ISSN 0165-0327. doi:10.1016/s0165-0327(96)00103-6. (原始内容存档于2018-10-24).

- ^ Carolina, Hardoy Maria; Giovanni, Carta Mauro. Strategy to Accelerate or Augment the Antidepressant Response and for An Early Onset of SSRI Activity. Adjunctive Amisulpride to Fluvoxamine in Major Depressive Disorder. Clinical Practice & Epidemiology in Mental Health. 2010-01-27, 6 (1): 1–3 [2018-10-24]. ISSN 1745-0179. PMID 20498696. doi:10.2174/1745017901006010001. (原始内容存档于2018-10-24).

- ^ Kaul, Vijay; Dutta, Shakti B.; Beg, Mirza A.; Bawa, Shalu; Anjoom, Mohammed; Singh, Nand K.; Dutta, Srihari. Comparative evaluation of amisulpride and escitalopram on Hamilton anxiety rating scale among depression patients in a tertiary care teaching hospital in Nepal. International Journal of Basic & Clinical Pharmacology. 2017-01-21, 4 (2): 349–353 [2018-10-24]. ISSN 2279-0780. doi:10.5455/2319-2003.ijbcp20150438. (原始内容存档于2018-06-14) (英语).

- ^ Sandoz Limited Summary of Product Characteristics, archived from the original on 2014-08-17, retrieved 2014-08-17

- ^ 22.0 22.1 22.2 "PRODUCT INFORMATION SOLIAN® TABLETS and SOLUTION" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆) (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Sanofi-Aventis Australia Pty Ltd. 9 September 2013. Retrieved 17 October 2013.

- ^ 23.0 23.1 Truven Health Analytics, Inc. DRUGDEX® System (Internet) [cited 2013 Sep 19]. Greenwood Village, CO: Thomsen Healthcare; 2013.

- ^ 24.0 24.1 Joint Formulary Committee (2013). British National Formulary (BNF) (65 ed.). London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. ISBN 978-0-85711-084-8.

- ^ 25.0 25.1 Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ^ Brunton, L; Chabner, B; Knollman, B (2010). Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics (12th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 978-0-07-162442-8.

- ^ McKeage, K; Plosker, GL (2004). "Amisulpride: a review of its use in the management of schizophrenia". CNS Drugs. 18 (13): 933–956. doi:10.2165/00023210-200418130-00007. ISSN 1172-7047 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). PMID 15521794 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Natesan, S; Reckless, GE; Barlow, KB; Nobrega, JN; Kapur, S (October 2008). "Amisulpride the 'atypical' atypical antipsychotic — Comparison to haloperidol, risperidone and clozapine". Schizophrenia Research. 105 (1–3): 224–235. doi:10.1016/j.schres.2008.07.005. PMID 18710798 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Isbister, GK; Balit, CR; Macleod, D; Duffull, SB (August 2010). "Amisulpride overdose is frequently associated with QT prolongation and torsades de pointes". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 30 (4): 391–395. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e3181e5c14c. PMID 20531221 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Joy, JP; Coulter, CV; Duffull, SB; Isbister, GK (August 2011). "Prediction of Torsade de Pointes From the QT Interval: Analysis of a Case Series of Amisulpride Overdoses". Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics. 90 (2): 243–245. doi:10.1038/clpt.2011.107. PMID 21716272 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ 31.0 31.1 31.2 Taylor, D; Paton, C; Shitij, K (2012). Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry (11th ed.). West Sussex: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-47-097948-8.

- ^ Levine, M; Ruha, AM (July 2012). "Overdose of atypical antipsychotics: clinical presentation, mechanisms of toxicity and management". CNS Drugs. 26 (7): 601–611. doi:10.2165/11631640-000000000-00000. PMID 22668123 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Roth, BL; Driscol, J. "PDSP Ki Database" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ^ 34.00 34.01 34.02 34.03 34.04 34.05 34.06 34.07 34.08 34.09 34.10 34.11 34.12 34.13 34.14 34.15 34.16 34.17 34.18 34.19 34.20 34.21 34.22 34.23 34.24 34.25 34.26 34.27 34.28 34.29 34.30 34.31 34.32 34.33 34.34 34.35 34.36 34.37 34.38 34.39 34.40 34.41 34.42 34.43 34.44 34.45 34.46 Abbas AI, Hedlund PB, Huang XP, Tran TB, Meltzer HY, Roth BL (2009). "Amisulpride is a potent 5-HT7 antagonist: relevance for antidepressant actions in vivo" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). Psychopharmacology. 205 (1): 119–28. doi:10.1007/s00213-009-1521-8. PMC 2821721 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). PMID 19337725 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ 35.0 35.1 Maitre, M.; Ratomponirina, C.; Gobaille, S.; Hodé, Y.; Hechler, V. (Apr 1994). "Displacement of [3H] gamma-hydroxybutyrate binding by benzamide neuroleptics and prochlorperazine but not by other antipsychotics". European Journal of Pharmacology. 256 (2): 211–214. doi:10.1016/0014-2999(94)90248-8. PMID 7914168 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Schoemaker H, Claustre Y, Fage D, Rouquier L, Chergui K, Curet O, Oblin A, Gonon F, Carter C, Benavides J, Scatton B (1997). "Neurochemical characteristics of amisulpride, an atypical dopamine D2/D3 receptor antagonist with both presynaptic and limbic selectivity". J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 280(1): 83–97. PMID 8996185 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Cassano, G. B.a; Jori, M. C.b. "Efficacy and safety of amisulpride 50 mg versus paroxetine 20 mg in major depression: a randomized, double-blind, parallel group study" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆). International Clinical Psychopharmacology: January 2002 - Volume 17 - Issue 1 - p 27-32

- ^ Blomme, Audrey; Conraux, Laurence; Poirier, Philippe; Olivier, Anne; Koenig, Jean-Jacques; Sevrin, Mireille; Durant, François; George, Pascal (2000), "Amisulpride, Sultopride and Sulpiride: Comparison of Conformational and Physico-Chemical Properties" (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆), Molecular Modeling and Prediction of Bioactivity, Springer US, pp. 404–405, doi:10.1007/978-1-4615-4141-7_97, ISBN 9781461368571, retrieved 2018-09-21

- ^ Lecrubier, Y.; et al. (2001). "Consensus on the Practical Use of Amisulpride, an Atypical Antipsychotic, in the Treatment of Schizophrenia". Neuropsychobiology. 44 (1): 41–46. doi:10.1159/000054913. PMID 11408792 (页面存档备份,存于互联网档案馆).

- ^ Kaplan, A. (2004). "Psychotropic Medications Around the World". Psychiatric Times. 21 (5).