Algerian history

| History of Algeria |

|---|

|

Much of the history of Algeria has taken place on the fertile coastal plain of North Africa, which is often called the Maghreb (or Maghreb). North Africa served as a transit region for people moving towards Europe or the Middle East, thus, the region's inhabitants have been influenced by populations from other areas, including the Carthaginians, Romans, and Vandals. The region was conquered by the Muslims in the early 8th century AD, but broke off from the Umayyad Caliphate after the Berber Revolt of 740. During the Ottoman period, Algeria became an important state in the Mediterranean sea which led to many naval conflicts. The last significant events in the country's recent history have been the Algerian War and Algerian Civil War.

Prehistory

Evidence of the early human occupation of Algeria is demonstrated by the discovery of 1.8 million year old Oldowan stone tools found at Ain Hanech in 1992.[1] In 1954 fossilised Homo erectus bones were discovered by C. Arambourg at Ternefine that are 700,000 years old. Neolithic civilization (marked by animal domestication and subsistence agriculture) developed in the Saharan and Mediterranean Maghrib between 6000 and 2000 BC. This type of economy, richly depicted in the Tassili n'Ajjer cave paintings in southeastern Algeria, predominated in the Maghrib until the classical period.

Numidia

Numidia (Berber: Inumiden; 202–40 BC) was the ancient kingdom of the Numidians located in northwest Africa, initially comprising the territory that now makes up modern-day Algeria, but later expanding across what is today known as Tunisia, Libya, and some parts of Morocco. The polity was originally divided between the Massylii in the east and the Masaesyli in the west. During the Second Punic War (218–201 BC), Masinissa, king of the Massylii, defeated Syphax of the Masaesyli to unify Numidia into one kingdom. The kingdom began as a sovereign state and later alternated between being a Roman province and a Roman client state.

Numidia, at its largest extent, was bordered by Mauretania to the west, at the Moulouya River,[2] Africa to the east (also exercising control over Tripolitania), the Mediterranean Sea to the north, and the Sahara to the south. It was one of the first major states in the history of Algeria and the Berbers.

War With Rome

By 112 BC, Jugurtha resumed his war with Adherbal. He incurred the wrath of Rome in the process by killing some Roman businessmen who were aiding Adherbal. After a brief war with Rome, Jugurtha surrendered and received a highly favourable peace treaty, which raised suspicions of bribery once more. The local Roman commander was summoned to Rome to face corruption charges brought by his political rival Gaius Memmius. Jugurtha was also forced to come to Rome to testify against the Roman commander, where Jugurtha was completely discredited once his violent and ruthless past became widely known, and after he had been suspected of murdering a Numidian rival.

War broke out between Numidia and the Roman Republic and several legions were dispatched to North Africa under the command of the Consul Quintus Caecilius Metellus Numidicus. The war dragged out into a long and seemingly endless campaign as the Romans tried to defeat Jugurtha decisively. Frustrated at the apparent lack of action, Metellus' lieutenant Gaius Marius returned to Rome to seek election as Consul. Marius was elected, and then returned to Numidia to take control of the war. He sent his Quaestor Sulla to neighbouring Mauretania in order to eliminate their support for Jugurtha. With the help of Bocchus I of Mauretania, Sulla captured Jugurtha and brought the war to a conclusive end. Jugurtha was brought to Rome in chains and was placed in the Tullianum.[3]

Jugurtha was executed by the Romans in 104 BC, after being paraded through the streets in Gaius Marius' Triumph.[4]

Independence

The Greek historians referred to these peoples as "Νομάδες" (i.e. Nomads), which by Latin interpretation became "Numidae" (but cf. also the correct use of Nomades).[5][6] Historian Gabriel Camps, however, disputes this claim, favoring instead an African origin for the term.[7]

The name appears first in Polybius (second century BC) to indicate the peoples and territory west of Carthage including the entire north of Algeria as far as the river Mulucha (Muluya), about 160 kilometres (100 mi) west of Oran.[8]

The Numidians were composed of two great tribal groups: the Massylii in eastern Numidia, and the Masaesyli in the west. During the first part of the Second Punic War, the eastern Massylii, under their king Gala, were allied with Carthage, while the western Masaesyli, under king Syphax, were allied with Rome. The Kingdom of Masaesyli under Syphax extended from the Moulouya river to Oued Rhumel.[9]

However, in 206 BC, the new king of the eastern Massylii, Masinissa, allied himself with Rome, and Syphax of the Masaesyli switched his allegiance to the Carthaginian side. At the end of the war, the victorious Romans gave all of Numidia to Masinissa of the Massylii.[8] At the time of his death in 148 BC, Masinissa's territory extended from the Moulouya to the boundary of the Carthaginian territory, and also southeast as far as Cyrenaica to the gulf of Sirte, so that Numidia entirely surrounded Carthage (Appian, Punica, 106) except towards the sea. Furthermore, after the capture of Syphax the king in modern day Morocco with his capital based in Tingis, Bokkar, had become a vassal of Massinissa.[10][11][12] Massinissa had also penetrated as far south beyond the Atlas to the Gaetuli and Fezzan was part of his domain.[13][14]

In 179 B.C. Masinissa had received a golden crown from the inhabitants of Delos as he had offered them a shipload of grain. A statue of Masinissa was set up in Delos in honour of him as well as an inscription dedicated to him in Delos by a native from Rhodes. His sons too had statues of them erected on the island of Delos and the King of Bithynia, Nicomedes, had also dedicated a statue to Masinissa.[15]

After the death of the long-lived Masinissa around 148 BC, he was succeeded by his son Micipsa. When Micipsa died in 118 BC, he was succeeded jointly by his two sons Hiempsal I and Adherbal and Masinissa's illegitimate grandson, Jugurtha, who was very popular among the Numidians. Hiempsal and Jugurtha quarrelled immediately after the death of Micipsa. Jugurtha had Hiempsal killed, which led to open war with Adherbal.[16]

Phoenician traders arrived on the North African coast around 900 BC and established Carthage (in present-day Tunisia) around 800 BC. During the classical period, Berber civilization was already at a stage in which agriculture, manufacturing, trade, and political organization supported several states. Trade links between Carthage and the Berbers in the interior grew, but territorial expansion also resulted in the enslavement or military recruitment of some Berbers and in the extraction of tribute from others.

The Carthaginian state declined because of successive defeats by the Romans in the Punic Wars, and in 146 BC, the city of Carthage was destroyed. As Carthaginian power waned, the influence of Berber leaders in the hinterland grew.

By the 2nd century BC, several large but loosely administered Berber kingdoms had emerged. After that, king Masinissa managed to unify Numidia under his rule.[17][18][19]

Roman empire

Christianity arrived in the 2nd century. By the end of the 4th century, the settled areas had become Christianized, and some Berber tribes had converted en masse.

After the fall of the Western Roman Empire, Algeria came under the control of the Vandal Kingdom. Later, the Eastern Roman Empire (also known as the Byzantine Empire) conquered Algeria from the Vandals, incorporating it into the Praetorian prefecture of Africa and later the Exarchate of Africa.

Medieval Muslim Algeria

From the 8th century Umayyad conquest of North Africa led by Musa bin Nusayr, Arab colonization started. The 11th century invasion of migrants from the Arabian peninsula brought oriental tribal customs. The introduction of Islam and Arabic had a profound impact on North Africa. The new religion and language introduced changes in social and economic relations, and established links with the Arab world through acculturation and assimilation.

The second Arab military expeditions into the Maghreb, between 642 and 669, resulted in the spread of Islam. The Umayyads (a Muslim dynasty based in Damascus from 661 to 750) recognised that the strategic necessity of dominating the Mediterranean dictated a concerted military effort on the North African front. By 711 Umayyad forces helped by Berber converts to Islam had conquered all of North Africa. In 750 the Abbasids succeeded the Umayyads as Muslim rulers and moved the caliphate to Baghdad. Under the Abbasids, Berber Kharijites Sufri Banu Ifran were opposed to Umayyad and Abbasids. After, the Rustumids (761–909) actually ruled most of the central Maghrib from Tahirt, southwest of Algiers. The imams gained a reputation for honesty, piety, and justice, and the court of Tahirt was noted for its support of scholarship. The Rustumid imams failed, however, to organise a reliable standing army, which opened the way for Tahirt's demise under the assault of the Fatimid dynasty.

The Fatimids left the rule of most of Algeria to the Zirids and Hammadid (972–1148), a Berber dynasty that centered significant local power in Algeria for the first time, but who were still at war with Banu Ifran (kingdom of Tlemcen) and Maghraoua (942-1068).[20] This period was marked by constant conflict, political instability, and economic decline. Following a large incursion of Arab Bedouin from Egypt beginning in the first half of the 11th century, the use of Arabic spread to the countryside, and sedentary Berbers were gradually Arabised.

The Almoravid ("those who have made a religious retreat") movement developed early in the 11th century among the Sanhaja Berbers of southern Morocco. The movement's initial impetus was religious, an attempt by a tribal leader to impose moral discipline and strict adherence to Islamic principles on followers. But the Almoravid movement shifted to engaging in military conquest after 1054. By 1106, the Almoravids had conquered the Maghreb as far east as Algiers and Morocco, and Spain up to the Ebro River.

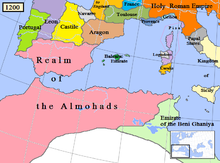

Like the Almoravids, the Almohads ("unitarians") found their inspiration in Islamic reform. The Almohads took control of Morocco by 1146, captured Algiers around 1151, and by 1160 had completed the conquest of the central Maghrib. The zenith of Almohad power occurred between 1163 and 1199. For the first time, the Maghrib was united under a local regime, but the continuing wars in Spain overtaxed the resources of the Almohads, and in the Maghrib their position was compromised by factional strife and a renewal of tribal warfare.

In the central Maghrib, the Abdalwadid founded a dynasty that ruled the Kingdom of Tlemcen in Algeria. For more than 300 years, until the region came under Ottoman suzerainty in the 16th century, the Zayanids kept a tenuous hold in the central Maghrib. Many coastal cities asserted their autonomy as municipal republics governed by merchant oligarchies, tribal chieftains from the surrounding countryside, or the privateers who operated out of their ports. Nonetheless, Tlemcen, the "pearl of the Maghrib," prospered as a commercial center.

Berber dynasties

According to historians of the Middle Ages, the Berbers were divided into two branches, both going back to their ancestors Mazigh. The two branches, called Botr and Barnès were divided into tribes, and each Maghreb region is made up of several tribes. The large Berber tribes or peoples are Sanhaja, Houara, Zenata, Masmuda, Kutama, Awarba, Barghawata ... etc. Each tribe is divided into sub tribes. All these tribes had independent and territorial decisions.[21]

Several Berber dynasties emerged during the Middle Ages: - In North and West Africa, in Spain (al-Andalus), Sicily, Egypt, as well as in the southern part of the Sahara, in modern-day Mali, Niger, and Senegal. The medieval historian Ibn Khaldun described the follying Berber dynasties: Zirid, Banu Ifran, Maghrawa, Almoravid, Hammadid, Almohad Caliphate, Marinid, Zayyanid, Wattasid, Meknes, Hafsid dynasty, Fatimids.[21]

The invasion of the Banu Hilal Arab tribes in the 11th century sacked Kairouan, and the area under Zirid control was reduced to the coastal region, and the Arab conquests fragmented into petty Bedouin emirates.[a]

Maghrawa Dynasty

The Maghrawa or Meghrawa (Arabic: المغراويون) were a large Zenata Berber tribal confederation whose cradle and seat of power was the territory located on the Chlef in the north-western part of today's Algeria, bounded by the Ouarsenis to the south, the Mediterranean Sea to the north and Tlemcen to the west. They ruled these areas on behalf of the Umayyad Caliphate of Cordoba at the end of the 10th century and during the first half of the 11th century. The Maghrawa confederation of zanata Berbers supposedly originated in the region of modern Algeria between Tlemcen and Tenes.[22]

The confederation of Maghrawa were the majority people of the central Maghreb among the Zenata (Gaetuli). Both nomadic and sedentary, the Maghrawa lived under the command of Maghrawa chiefs or Zenata. Algiers has been the territory of the Maghrawa since ancient times.[23] The name Maghrawa was transcribed into Greek by historians. The great kingdom of the Maghrawa was located between Algiers, Cherchell, Ténès, Chlef, Miliana and Médéa. The Maghrawa imposed their domination in the Aurès.[24][when?] Chlef and its surroundings were populated by the Maghrawa according to Ibn Khaldun.[25] The Maghrawa settled and extended their domination throughout the Dahra and beyond Miliana to the Tafna wadi near Tlemcen,[when?] and were found as far away as Mali.[citation needed]

The Maghrawa were one of the first Berber tribes to submit to Islam in the 7th century.[26] They supported Uqba ibn Nafi in his campaign to the Atlantic in 683. They defected from Sunni Islam and became Kharijite Muslims from the 8th century, and allied first with the Idrisids, and, from the 10th century on, with the Umayyads of Córdoba in Al-Andalus. As a result, they were caught up in the Umayyad-Fatimid conflict in Morocco and Algeria. Although they won a victory over the allies of the Fatimids in 924, they soon allied with them. When they switched back to the side of Córdoba, the Zirids briefly took control over most of Morocco,[27][25] and ruled on behalf of the Fatimids. In 976/977 the Maghrawa conquered Sijilmasa from the Banu Midrar,[28] and in 980 were able to drive the Miknasa out of Sijilmasa as well.[25]

The Maghrawa reached their peak under Ziri ibn Atiyya (to 1001), who achieved supremacy in Fez under Umayyad suzerainty, and expanded their territory at the expense of the Banu Ifran in the northern Maghreb – another Zenata tribe whose alliances had shifted often between the Fatimids and the Umayyads of Córdoba.[29] Ziri ibn Atiyya conquered as much as he could of what is now northern Morocco and was able to achieve supremacy in Fez by 987.[28] In 989 he defeated his enemy, Abu al-Bahār, which resulted in Ziri ruling from Zab to Sous Al-Aqsa, in 991 achieving supremacy in the western Maghreb.[30][28] As a result of his victory he was invited to Córdoba by Ibn Abi 'Amir al-Mansur (also Latinized as Almanzor), the regent of Caliph Hisham II and de facto ruler of the Caliphate of Córdoba.[25] Ziri brought many gifts and Al-Mansur housed him in a lavish palace, but Ziri soon returned to North Africa.[31][29] The Banu Ifran took advantage of his absence and, under Yaddū, managed to capture Fez.[25][full citation needed] After a bloody struggle, Ziri reconquered Fez in 993 and displayed Yaddū's severed head on its walls.[citation needed]

A period of peace followed, in which Ziri founded the city of Oujda in 994 and made it his capital.[32][29] However, Ziri was loyal to the Umayyad caliphs in Cordoba and increasingly resented the way that Ibn Abi 'Amir was holding Hisham II captive while progressively usurping his power. In 997 Ziri rejected Ibn Abi 'Amir's authority and declared himself a direct supporter of Caliph Hisham II.[31][29] Ibn Abi 'Amir sent an invasion force to Morocco.[31] After three unsuccessful months, Ibn Abi 'Amir's army was forced to retreat to the safety of Tangiers, so Ibn Abi 'Amir sent a powerful reinforcements under his son Abd al-Malik.[citation needed] The armies clashed near Tangiers, and in this battle, Ziri was stabbed by an African soldier who reported to Abd al-Malik that he had seriously wounded the Zenata leader. Abd al-Malik pressed home the advantage, and the wounded Ziri fled, hotly pursued by the Caliph's army. The inhabitants of Fez would not let him enter the city, but opened the gates to Abd al-Malik on 13 October 998. Ziri fled to the Sahara, where he rallied the Zenata tribes and overthrew the unpopular remnants of the Idrisid dynasty at Tiaret. He was able to expand his territory to include Tlemcen and other parts of western Algeria, this time under Fatimid protection. Ziri died in 1001 of the after-effects of the stab wounds. He was succeeded by his son Al-Mu'izz, who made peace with Al-Mansur, and regained possession of all his father's former territories.[citation needed]

A revolt against the Andalusian Umayyads was put down by Ibn Abi 'Amir, although the Maghrawa were able to regain power in Fez. Under the succeeding rulers al-Muizz (1001–1026), Hamman (1026–1039) and Dunas (1039), they consolidated their rule in northern and central Morocco.[citation needed]

Internal power struggles after 1060 enabled the Almoravid dynasty to conquer the Maghrawa realm in 1070 and put an end to their rule. In the mid 11th century the Maghrawa still controlled most of Morocco, notably most of the Sous and Draa River area as well as Aghmat, Fez and Sijilmasa.[28] Later, Zenata power declined. The Maghrawa and Banu Ifran began oppressing their subjects, shedding their blood, violating their women, breaking into homes to seize food and depriving traders of their goods. Anyone who tried to ward them off was killed.[33]

Zirid Dynasty

The Zirid dynasty (Arabic: الزيريون, romanized: az-zīriyyūn), Banu Ziri (Arabic: بنو زيري, romanized: banū zīrī), or the Zirid state (Arabic: الدولة الزيرية, romanized: ad-dawla az-zīriyya)[34] was a Sanhaja Berber dynasty from modern-day Algeria which ruled the central Maghreb from 972 to 1014 and Ifriqiya (eastern Maghreb) from 972 to 1148.[35][36]

Descendants of Ziri ibn Manad, a military leader of the Fatimid Caliphate and the eponymous founder of the dynasty, the Zirids were emirs who ruled in the name of the Fatimids. The Zirids gradually established their autonomy in Ifriqiya through military conquest until officially breaking with the Fatimids in the mid-11th century. The rule of the Zirid emirs opened the way to a period in North African history where political power was held by Berber dynasties such as the Almoravid dynasty, Almohad Caliphate, Zayyanid dynasty, Marinid Sultanate and Hafsid dynasty.[37]

Under Buluggin ibn Ziri the Zirids extended their control westwards and briefly occupied Fez and much of present-day Morocco after 980, but encountered resistance from the local Zenata Berbers who gave their allegiance to the Caliphate of Cordoba.[38][39][40][41] To the east, Zirid control was extended over Tripolitania after 978[42] and as far as Ajdabiya (in present-day Libya).[43][44] One member of the dynastic family, Zawi ibn Ziri, revolted and fled to al-Andalus, eventually founding the Taifa of Granada in 1013, after the collapse of the Caliphate of Cordoba.[36] Another branch of the Zirids, the Hammadids, broke away from the main branch after various internal disputes and took control of the territories of the central Maghreb after 1015.[45] The Zirids proper were then designated as Badicides and occupied only Ifriqiya between 1048 and 1148.[46] They were based in Kairouan until 1057, when they moved the capital to Mahdia on the coast.[47] The Zirids of Ifriqiya also intervened in Sicily during the 11th century, as the Kalbids, the dynasty who governed the island on behalf of the Fatimids, fell into disorder.[48]

The Zirids of Granada surrendered to the Almoravids in 1090,[49] but the Badicides and the Hammadids remained independent during this time. Sometime between 1041 and 1051 the Zirid ruler al-Mu'izz ibn Badis renounced the Fatimid Caliphs and recognized the Sunni Muslim Abbasid Caliphate.[50] In retaliation, the Fatimids instigated the migration of the Banu Hilal tribe to the Maghreb, dealing a serious blow to Zirid power in Ifriqiya.[47][51] In the 12th century, the Hilalian invasions combined with the attacks of the Normans of Sicily along the coast further weakened Zirid power. The last Zirid ruler, al-Hasan, surrendered Mahdia to the Normans in 1148, thus ending independent Zirid rule.[51] The Almohad Caliphate conquered the central Maghreb and Ifriqiya by 1160, ending the Hammadid dynasty in turn and finally unifying the whole of the Maghreb.[38][52]

Origins and establishment

The Zirids were Sanhaja Berbers, from the sedentary Talkata tribe,[53][54] originating from the area of modern Algeria. In the 10th century this tribe served as vassals of the Fatimid Caliphate, an Isma'ili Shi'a state that challenged the authority of the Sunni Abbasid caliphs. The progenitor of the Zirid dynasty, Ziri ibn Manad (r. 935–971) was installed as governor of the central Maghreb (roughly north-eastern Algeria today) on behalf of the Fatimids, guarding the western frontier of the Fatimid Caliphate.[55][56] With Fatimid support Ziri founded his own capital and palace at 'Ashir, south-east of Algiers, in 936.[57][58][59] He proved his worth as a key ally in 945, during the Kharijite rebellion of Abu Yazid, when he helped break Abu Yazid's siege of the Fatimid capital, Mahdia.[60][61] After playing this valuable role, he expanded 'Ashir with a new palace circa 947.[57][62] In 959 he aided Jawhar al-Siqili on a Fatimid military expedition which successfully conquered Fez and Sijilmasa in present-day Morocco. On their return home to the Fatimid capital they paraded the emir of Fez and the “Caliph” Ibn Wasul of Sijilmasa in cages in a humiliating manner.[63][64][65] After this success, Ziri was also given Tahart to govern on behalf of the Fatimids.[66] He was eventually killed in battle against the Zanata in 971.[58][67]

When the Fatimids moved their capital to Egypt in 972, Ziri's son Buluggin ibn Ziri (r. 971–984) was appointed viceroy of Ifriqiya. He soon led a new expedition west and by 980 he had conquered Fez and most of Morocco, which had previously been retaken by the Umayyads of Cordoba in 973.[68][69] He also led a successful expedition to Barghawata territory, from which he brought back a large number of slaves to Ifriqiya.[70] In 978 the Fatimids also granted Buluggin overlordship of Tripolitania (in present-day Libya), allowing him to appoint his own governor in Tripoli. In 984 Buluggin died in Sijilmasa from an illness and his successor decided to abandon Morocco in 985.[51][71][72]

Buluggin's successors and the first divisions

After Buluggin's death, rule of the Zirid state passed to his son, Al-Mansur ibn Buluggin (r. 984–996), and continued through his descendants. However, this alienated the other sons of Ziri ibn Manad who now found themselves excluded from power. In 999 many of these brothers launched a rebellion in 'Ashir against Badis ibn al-Mansur (r. 996–1016), Buluggin's grandson, marking the first serious break in the unity of the Zirids.[73] The rebels were defeated in battle by Hammad ibn Buluggin, Badis' uncle, and most of the brothers were killed. The only remaining brother of stature, Zawi ibn Ziri, led the remaining rebels westwards and sought new opportunity in al-Andalus under the Umayyads Caliphs of Cordoba, the former enemies of the Fatimids and Zirids.[73][74] He and his followers eventually founded an independent kingdom in al-Andalus, the Taifa of Granada, in 1013.[75][76]

After 1001 Tripolitania broke away under the leadership of Fulful ibn Sa'id ibn Khazrun, a Maghrawa leader who founded the Banu Khazrun dynasty, which endured until 1147.[77][42][78] Fulful fought a protracted war against Badis ibn al-Mansur and sought outside help from the Fatimids and even from the Umayyads of Cordoba, but after his death in 1009 the Zirids were able to retake Tripoli for a time. The region nonetheless remained effectively under control of the Banu Khazrun, who fluctuated between practical autonomy and full independence, often playing the Fatimids and the Zirids against each other.[79][80][42][81] The Zirids finally lost Tripoli to them in 1022.[82]

Badis appointed Hammad ibn Buluggin as governor of 'Ashir and the western Zirid territories in 997.[83] He gave Hammad a great deal of autonomy, allowing him to campaign against the Zanata and control any new territories he conquered.[60][84] Hammad constructed his own capital, the Qal'at Bani Hammad, in 1008, and in 1015 he rebelled against Badis and declared himself independent altogether, while also recognizing the Abbasids instead of the Fatimids as caliphs. Badis besieged Hammad's capital and nearly subdued him, but died in 1016 shortly before this could be accomplished. His son and successor, al-Mu'izz ibn Badis (r. 1016–1062), defeated Hammad in 1017, which forced the negotiation of a peace agreement between them. Hammad resumed his recognition of the Fatimids as caliphs but remained independent, forging a new Hammadid state which controlled a large part of present-day Algeria thereafter.[84]

Apogee in Ifriqiya

The Zirid period of Ifriqiya is considered a high point in its history, with agriculture, industry, trade and learning, both religious and secular, all flourishing, especially in their capital, Qayrawan (Kairouan).[85] The early reign of al-Mu'izz ibn Badis (r. 1016–1062) was particularly prosperous and marked the height of their power in Ifriqiya.[60] In the eleventh century, when the question of Berber origin became a concern, the dynasty of al-Mu'izz started, as part of the Zirids' propaganda, to emphasize its supposed links to the Himyarite kings as a title to nobility, a theme that was taken the by court historians of the period.[86][87] Management of the area by later Zirid rulers was neglectful as the agricultural economy declined, prompting an increase in banditry among the rural population.[85] The relationship between the Zirids their Fatimid overlords varied - in 1016 thousands of Shiites died in rebellions in Ifriqiya, and the Fatimids encouraged the defection of Tripolitania from the Zirids, but nevertheless the relationship remained close. In 1049 the Zirids broke away completely by adopting Sunni Islam and recognizing the Abbasids of Baghdad as rightful Caliphs, a move which was popular with the urban Arabs of Kairouan.[88][89]

In Sicily the Kalbids continued to govern on behalf of the Fatimids but the island descended into political disarray during the 11th century,[48] inciting the Zirids to intervene on the island. In 1025 (or 1021[90]), al-Mu'izz ibn Badis sent a fleet of 400 ships to the island in response to the Byzantines reconquering Calabria (in southern Italy) from the Muslims, but the fleet was lost in a powerful storm off the coast of Pantelleria.[60][90][91] In 1036, the Muslim population of the island request aid from al-Mu'izz to overthrow the Kalbid emir Ahmad ibn Yusuf al-Akhal, whose rule they considered flawed and unjust.[48] The request also contained a pledge to recognize al-Mu'izz as their ruler.[90] Al-Mu'izz, eager to expand his influence after the fragmentation of Zirid North Africa, accepted and sent his son, 'Abdallah, to the island with a large army.[90][48][92] Al-Akhal, who had been in negotiations with the Byzantines, requested help from them. A Byzantine army intervened and defeated the Zirid army on the island, but it then withdrew to Calabria, allowing 'Abdallah to finish off al-Akhal.[48] Al-Akhal was besieged in Palermo and killed in 1038.[90][48][61] 'Abdallah was subsequently forced to withdraw from the island, either due to the ever-divided Sicilians turning against him or due to another Byzantine invasion in 1038, led by George Maniakes.[92][90] Another Kalbid amir, al-Hasan al-Samsam, was elected to govern Sicily, but Muslim rule there disintegrated into various petty factions leading up to the Norman conquest of the island in the second half of the 11th century.[93][48][90]

Hilalian invasions and withdrawal to Mahdia

The Zirids renounced the Fatimids and recognized the Abbasid Caliphs in 1048-49,[60] or sometime between 1041 and 1051.[43][61][b] In retaliation, the Fatimids sent the Arab tribes of the Banu Hilal and the Banu Sulaym to the Maghreb.[60][84] The Banu Sulaym settled first in Cyrenaica, but the Banu Hilal continued towards Ifriqiya.[84] The Zirids attempted to stop their advance towards Ifriqiya, they sent 30,000 Sanhaja cavalry to meet the 3,000 Arab cavalry of Banu Hilal in the Battle of Haydaran of 14 April 1052.[94] Nevertheless, the Zirids were decisively defeated and were forced to retreat, opening the road to Kairouan for the Hilalian Arab cavalry.[94][95][96] The resulting anarchy devastated the previously flourishing agriculture, and the coastal towns assumed a new importance as conduits for maritime trade and bases for piracy against Christian shipping, as well as being the last holdout of the Zirids.[95] The Banu Hilal invasions eventually forced al-Mu'izz ibn Badis to abandon Kairouan in 1057 and move his capital to Mahdia, while the Banu Hilal largely roamed and pillaged the interior of the former Zirid territories.[47][60]

As a result of the Zirid withdrawal, various local principalities emerged in different areas. In Tunis, the shaykhs of the city elected Abd al-Haqq ibn Abd al-Aziz ibn Khurasan (r. 1059-1095) as local ruler. He founded the local Banu Khurasan dynasty that governed the city thereafter, alternately recognizing the Hammadids or the Zirids as overlords depending on the circumstances.[97][98] In Qabis (Gabès), the Zirid governor, al-Mu'izz ibn Muhammad ibn Walmiya remained loyal until 1062 when, outraged by the expulsion of his two brothers from Mahdia by al-Mu'izz ibn Badis, he declared his independence and placed himself under the protection of Mu'nis ibn Yahya, a chief of Banu Hilal.[99][100] Sfaqus (Sfax) was declared independent by the Zirid governor, Mansur al-Barghawati, who was murdered and succeeded by his cousin Hammu ibn Malil al-Barghawati.[101]

Al-Mui'zz ibn Badis was succeeded by his son, Tamim ibn al-Mu'izz (r. 1062-1108), who spent much of his reign attempting to restore Zirid power in the region. In 1063 he repelled a siege of Mahdia by the independent ruler of Sfax while also capturing the important port of Sus (Sousse).[102] Meanwhile, the Hammadid ruler al-Nasir ibn 'Alannas (r. 1062-1088) began to intervene in Ifriqiya around this time, having his sovereignty recognized in Sfax, Tunis, and Kairouan. Tamim organized a coalition with some of the Banu Hilal and Banu Sulaym tribes and succeeded in inflicting a heavy defeat on al-Nasir at the Battle of Sabiba in 1065. The war between the Zirids and Hammadids continued until 1077, when a truce was negotiated, sealed by a marriage between Tamim and one of al-Nasir's daughters.[103] In 1074 Tamim sent a naval expedition to Calabria where they ravaged the Italian coasts, plundered Nicotera and enslaved many of its inhabitants. The next year (1075) another Zirid raid resulted in the capture of Mazara in Sicily; however, the Zirid emir rethought his involvement in Sicily and decided to withdraw, abandoning what they had briefly held.[104] In 1087, the Zirid capital, Mahdia, was sacked by the Pisans.[105] According to Ettinghausen, Grabar, and Jenkins-Madina, the Pisa Griffin is believed to have been part of the spoils taken during the sack.[106] In 1083 Mahdia was besieged by a chief of the Banu Hilal, Malik ibn 'Alawi. Unable to take the city, Malik instead turned to Kairouan and captured that city, but Tamim marched out with his entire army and defeated the Banu Hilal forces, at which point he also brought Kairouan back under Zirid control.[107] He went on to capture Gabès in 1097 and Sfax in 1100.[107] Gabès, however, soon declared itself independent again under the leadership of the Banu Jami', a family from the Riyahi branch of the Banu Hilal.[100][99]

Tamim's son and successor, Yahya ibn Tamim (r. 1108-1116), formally recognized the Fatimid caliphs again and received an emissary from Cairo in 1111.[107] He captured an important fortress near Carthage called Iqlibiya and his fleet launched raids against Sardinia and Genoa, bringing back many captives.[107] He was assassinated in 1116 and succeeded by his son, 'Ali ibn Yahya (r. 1116-1121).[107] 'Ali continued to recognize the Fatimids, receiving another embassy from Cairo in 1118.[108] He imposed his authority on Tunis, but failed to recapture Gabès from its local ruler, Rafi' ibn Jami', whose counterattack he then had to repel from Mahdia.[108][99] He was succeeded by his son al-Hasan in 1121, the last Zirid ruler.[61]

End of Zirid rule

During the 1130s and 1140s the Normans of Sicily began to capture cities and islands along the coast of Ifriqiya.[109] Jerba was captured in 1135 and Tripoli was captured in 1146. In 1148, the Normans captured Sfax, Gabès, and Mahdia.[109][77] In Mahdia, the population was weakened by years of famine and the bulk of the Zirid army was away on another campaign when the Norman fleet, commanded by George of Antioch, arrived off the coast. Al-Hasan decided to abandon the city, leaving it to be occupied, which effectively ended the Zirid dynasty's rule.[60][110] Al-Hasan fled to the citadel of al-Mu'allaqa near Carthage and stayed there for a several months. He planned to flee to the Fatimid court in Egypt but the Norman fleet blocked his way, so instead he headed west, making for the Almohad court of 'Abd al-Mu'min in Marrakesh. He obtained permission from Yahya ibn al-'Aziz, the Hammadid ruler, to cross his territory, but after entering Hammadid territory he was detained and placed under house arrest in Algiers.[60][110] When 'Abd al-Mu'min captured Algiers in 1151, he freed al-Hasan, who accompanied him back to Marrakesh. Later, when 'Abd al-Mu'min conquered Mahdia in 1160, placing all of Ifriqiya under Almohad rule, al-Hasan was with him.[52][60] 'Abd al-Mu'min appointed him governor of Mahdia, where he remained, residing in the suburb of Zawila, until 'Abd al-Mu'min's death in 1163. The new Almohad caliph, Abu Ya'qub Yusuf, subsequently ordered him to come back to Marrakesh, but al-Hasan died along the way in Tamasna in 1167.[60][61]

Hammadid Dynasty

The Hammadid dynasty (Arabic: الحمّاديون) was a branch of the Sanhaja Berber dynasty that ruled an area roughly corresponding to north-eastern modern Algeria between 1008 and 1152. The state reached its peak under Nasir ibn Alnas during which it was briefly the most important state in Northwest Africa.[111]

The Hammadid dynasty's first capital was at Qalaat Beni Hammad. It was founded in 1007, and is now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. When the area was sacked by the Banu Hilal tribe, the Hammadids moved their capital to Béjaïa in 1090.

Almohad Caliphate

The Almohad Caliphate (IPA: /ˈælməhæd/; Arabic: خِلَافَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or دَوْلَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِينَ or ٱلدَّوْلَةُ ٱلْمُوَحِّدِيَّةُ from

Arabic: ٱلْمُوَحِّدُونَ, romanized: al-Muwaḥḥidūn, lit. 'those who profess the unity of God'[112][113][114]: 246 ) was a North African Berber Muslim empire founded in the 12th century. At its height, it controlled much of the Iberian Peninsula (Al Andalus) and North Africa (the Maghreb).[115][116][117]

The Almohad docrtine was founded by Ibn Tumart among the Berber Masmuda tribes, but the Almohad caliphate and its ruling dynasty were founded after his death by Abd al-Mu'min al-Gumi,[118][119][120][121][122] which was born in the Hammadid region of Tlemcen, Algeria.[123] Around 1120, Ibn Tumart first established a Berber state in Tinmel in the Atlas Mountains.[115] Under Abd al-Mu'min (r. 1130–1163) they succeeded in overthrowing the ruling Almoravid dynasty governing Morocco in 1147, when he conquered Marrakesh and declared himself caliph. They then extended their power over all of the Maghreb by 1159. Al-Andalus soon followed, and all of Muslim Iberia was under Almohad rule by 1172.[124]

The turning point of their presence in the Iberian Peninsula came in 1212, when Muhammad III, "al-Nasir" (1199–1214) was defeated at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in the Sierra Morena by an alliance of the Christian forces from Castile, Aragon and Navarre. Much of the remaining territories of al-Andalus were lost in the ensuing decades, with the cities of Córdoba and Seville falling to the Christians in 1236 and 1248 respectively.

The Almohads continued to rule in Africa until the piecemeal loss of territory through the revolt of tribes and districts enabled the rise of their most effective enemies, the Marinids, from northern Morocco in 1215. The last representative of the line, Idris al-Wathiq, was reduced to the possession of Marrakesh, where he was murdered by a slave in 1269; the Marinids seized Marrakesh, ending the Almohad domination of the Western Maghreb.

Origins

The Almohad movement originated with Ibn Tumart, a member of the Masmuda, a Berber tribal confederation of the Atlas Mountains of southern Morocco. At the time, Morocco, western Algeria and Spain (al-Andalus), were under the rule of the Almoravids, a Sanhaja Berber dynasty. Early in his life, Ibn Tumart went to Spain to pursue his studies, and thereafter to Baghdad to deepen them. In Baghdad, Ibn Tumart attached himself to the theological school of al-Ash'ari, and came under the influence of the teacher al-Ghazali. He soon developed his own system, combining the doctrines of various masters. Ibn Tumart's main principle was a strict unitarianism (tawhid), which denied the independent existence of the attributes of God as being incompatible with His unity, and therefore a polytheistic idea. Ibn Tumart represented a revolt against what he perceived as anthropomorphism in Muslim orthodoxy. His followers would become known as the al-Muwaḥḥidūn ("Almohads"), meaning those who affirm the unity of God.

After his return to the Maghreb c. 1117, Ibn Tumart spent some time in various Ifriqiyan cities, preaching and agitating, heading riotous attacks on wine-shops and on other manifestations of laxity. He laid the blame for the latitude on the ruling dynasty of the Almoravids, whom he accused of obscurantism and impiety. He also opposed their sponsorship of the Maliki school of jurisprudence, which drew upon consensus (ijma) and other sources beyond the Qur'an and Sunnah in their reasoning, an anathema to the stricter Zahirism favored by Ibn Tumart. His antics and fiery preaching led fed-up authorities to move him along from town to town. After being expelled from Bejaia, Ibn Tumart set up camp in Mellala, in the outskirts of the city, where he received his first disciples – notably, al-Bashir (who would become his chief strategist) and Abd al-Mu'min (a Zenata Berber, who would later become his successor).

In 1120, Ibn Tumart and his small band of followers proceeded to Morocco, stopping first in Fez, where he briefly engaged the Maliki scholars of the city in debate. He even went so far as to assault the sister[citation needed] of the Almoravid emir ʿAli ibn Yusuf, in the streets of Fez, because she was going about unveiled, after the manner of Berber women. After being expelled from Fez, he went to Marrakesh, where he successfully tracked down the Almoravid emir Ali ibn Yusuf at a local mosque, and challenged the emir, and the leading scholars of the area, to a doctrinal debate. After the debate, the scholars concluded that Ibn Tumart's views were blasphemous and the man dangerous, and urged him to be put to death or imprisoned. But the emir decided merely to expel him from the city.

Ibn Tumart took refuge among his own people, the Hargha, in his home village of Igiliz (exact location uncertain), in the Sous valley. He retreated to a nearby cave, and lived out an ascetic lifestyle, coming out only to preach his program of puritan reform, attracting greater and greater crowds. At length, towards the end of Ramadan in late 1121, after a particularly moving sermon, reviewing his failure to persuade the Almoravids to reform by argument, Ibn Tumart 'revealed' himself as the true Mahdi, a divinely guided judge and lawgiver, and was recognized as such by his audience. This was effectively a declaration of war on the Almoravid state.

On the advice of one of his followers, Omar Hintati, a prominent chieftain of the Hintata, Ibn Tumart abandoned his cave in 1122 and went up into the High Atlas, to organize the Almohad movement among the highland Masmuda tribes. Besides his own tribe, the Hargha, Ibn Tumart secured the adherence of the Ganfisa, the Gadmiwa, the Hintata, the Haskura, and the Hazraja to the Almohad cause. Around 1124, Ibn Tumart erected the ribat of Tinmel, in the valley of the Nfis in the High Atlas, an impregnable fortified complex, which would serve both as the spiritual center and military headquarters of the Almohad movement.

For the first eight years, the Almohad rebellion was limited to a guerilla war along the peaks and ravines of the High Atlas. Their principal damage was in rendering insecure (or altogether impassable) the roads and mountain passes south of Marrakesh – threatening the route to all-important Sijilmassa, the gateway of the trans-Saharan trade. Unable to send enough manpower through the narrow passes to dislodge the Almohad rebels from their easily defended mountain strong points, the Almoravid authorities reconciled themselves to setting up strongholds to confine them there (most famously the fortress of Tasghîmût that protected the approach to Aghmat, which was conquered by the Almohads in 1132[114]), while exploring alternative routes through more easterly passes.

Ibn Tumart organized the Almohads as a commune, with a minutely detailed structure. At the core was the Ahl ad-dār ("House of the Mahdi:), composed of Ibn Tumart's family. This was supplemented by two councils: an inner Council of Ten, the Mahdi's privy council, composed of his earliest and closest companions; and the consultative Council of Fifty, composed of the leading sheikhs of the Masmuda tribes. The early preachers and missionaries (ṭalaba and huffāẓ) also had their representatives. Militarily, there was a strict hierarchy of units. The Hargha tribe coming first (although not strictly ethnic; it included many "honorary" or "adopted" tribesmen from other ethnicities, e.g. Abd al-Mu'min himself). This was followed by the men of Tinmel, then the other Masmuda tribes in order, and rounded off by the black fighters, the ʻabīd. Each unit had a strict internal hierarchy, headed by a mohtasib, and divided into two factions: one for the early adherents, another for the late adherents, each headed by a mizwar (or amzwaru); then came the sakkakin (treasurers), effectively the money-minters, tax-collectors, and bursars, then came the regular army (jund), then the religious corps – the muezzins, the hafidh and the hizb – followed by the archers, the conscripts, and the slaves.[125] Ibn Tumart's closest companion and chief strategist, al-Bashir, took upon himself the role of "political commissar", enforcing doctrinal discipline among the Masmuda tribesmen, often with a heavy hand.

In early 1130, the Almohads finally descended from the mountains for their first sizeable attack in the lowlands. It was a disaster. The Almohads swept aside an Almoravid column that had come out to meet them before Aghmat, and then chased their remnant all the way to Marrakesh. They laid siege to Marrakesh for forty days until, in April (or May) 1130, the Almoravids sallied from the city and crushed the Almohads in the bloody Battle of al-Buhayra (named after a large garden east of the city). The Almohads were thoroughly routed, with huge losses. Half their leadership was killed in action, and the survivors only just managed to scramble back to the mountains.[126]

Ibn Tumart died shortly after, in August 1130. That the Almohad movement did not immediately collapse after such a devastating defeat and the death of their charismatic Mahdi, is likely due to the skills of his successor, Abd al-Mu'min.[127]: 70 Ibn Tumart's death was kept a secret for three years, a period which Almohad chroniclers described as a ghayba or "occultation". This period likely gave Abd al-Mu'min time to secure his position as successor to the political leadership of the movement.[127]: 70 Although a Zenata Berber from Tagra (Algeria),[128] and thus an alien among the Masmuda of southern Morocco, Abd al-Mu'min nonetheless saw off his principal rivals and hammered wavering tribes back to the fold. In an ostentatious gesture of defiance, in 1132, if only to remind the emir that the Almohads were not finished, Abd al-Mu'min led an audacious night operation that seized Tasghîmût fortress and dismantled it thoroughly, carting off its great gates back to Tinmel.[citation needed] Three years after Ibn Tumart's death he was officially proclaimed "Caliph".[129]

In order to neutralise the Masmudas, to whom he was a stranger, Abd al-Mumin relied on his tribe of origin, the Kumiyas (a Berber tribe from Orania), which he integrated massively into the army and within the Almohad power.[130][131][132] He thus appointed his son as his successor and his other children as governors of the provinces of the Caliphate.[133] The Kumiyas would later form the bodyguard of Abd al Mumin and his successor.[134] In addition, he also relied on Arabs, representatives of the great Hilalian families, whom he deported to Morocco to weaken the influence of the Masmuda sheikhs. These moves have the effect of advancing the Arabisation of the future Morocco.[135]

Al-Andalus

Abd al-Mu'min then came forward as the lieutenant of the Mahdi Ibn Tumart. Between 1130 and his death in 1163, Abd al-Mu'min not only rooted out the Almoravids, but extended his power over all northern Africa as far as Egypt, becoming amir of Marrakesh in 1147.

Al-Andalus followed the fate of Africa. Between 1146 and 1173, the Almohads gradually wrested control from the Almoravids over the Moorish principalities in Iberia. The Almohads transferred the capital of Muslim Iberia from Córdoba to Seville. They founded a great mosque there; its tower, the Giralda, was erected in 1184 to mark the accession of Ya'qub I. The Almohads also built a palace there called Al-Muwarak on the site of the modern day Alcázar of Seville.

The Almohad princes had a longer and more distinguished career than the Almoravids. The successors of Abd al-Mumin, Abu Yaqub Yusuf (Yusuf I, ruled 1163–1184) and Abu Yusuf Yaqub al-Mansur (Yaʻqūb I, ruled 1184–1199), were both able men. Initially their government drove many Jewish and Christian subjects to take refuge in the growing Christian states of Portugal, Castile, and Aragon. Ultimately they became less fanatical than the Almoravids, and Ya'qub al-Mansur was a highly accomplished man who wrote a good Arabic style and protected the philosopher Averroes. In 1190–1191, he campaigned in southern Portugal and won back territory lost in 1189. His title of "al-Manṣūr" ("the Victorious") was earned by his victory over Alfonso VIII of Castile in the Battle of Alarcos (1195).

From the time of Yusuf II, however, the Almohads governed their co-religionists in Iberia and central North Africa through lieutenants, their dominions outside Morocco being treated as provinces. When Almohad emirs crossed the Straits it was to lead a jihad against the Christians and then return to Morocco.[136]

Holding years

In 1212, the Almohad Caliph Muhammad 'al-Nasir' (1199–1214), the successor of al-Mansur, after an initially successful advance north, was defeated by an alliance of the four Christian kings of Castile, Aragón, Navarre, and Portugal, at the Battle of Las Navas de Tolosa in the Sierra Morena. The battle broke the Almohad advance, but the Christian powers remained too disorganized to profit from it immediately.

Before his death in 1213, al-Nasir appointed his young ten-year-old son as the next caliph Yusuf II "al-Mustansir". The Almohads passed through a period of effective regency for the young caliph, with power exercised by an oligarchy of elder family members, palace bureaucrats and leading nobles. The Almohad ministers were careful to negotiate a series of truces with the Christian kingdoms, which remained more-or-less in place for next fifteen years (the loss of Alcácer do Sal to the Kingdom of Portugal in 1217 was an exception).

In early 1224, the youthful caliph died in an accident, without any heirs. The palace bureaucrats in Marrakesh, led by the wazir Uthman ibn Jam'i, quickly engineered the election of his elderly grand-uncle, Abd al-Wahid I 'al-Makhlu', as the new Almohad caliph. But the rapid appointment upset other branches of the family, notably the brothers of the late al-Nasir, who governed in al-Andalus. The challenge was immediately raised by one of them, then governor in Murcia, who declared himself Caliph Abdallah al-Adil. With the help of his brothers, he quickly seized control of al-Andalus. His chief advisor, the shadowy Abu Zayd ibn Yujjan, tapped into his contacts in Marrakesh, and secured the deposition and assassination of Abd al-Wahid I, and the expulsion of the al-Jami'i clan.

This coup has been characterized as the pebble that finally broke al-Andalus. It was the first internal coup among the Almohads. The Almohad clan, despite occasional disagreements, had always remained tightly knit and loyally behind dynastic precedence. Caliph al-Adil's murderous breach of dynastic and constitutional propriety marred his acceptability to other Almohad sheikhs. One of the recusants was his cousin, Abd Allah al-Bayyasi ("the Baezan"), the Almohad governor of Jaén, who took a handful of followers and decamped for the hills around Baeza. He set up a rebel camp and forged an alliance with the hitherto quiet Ferdinand III of Castile. Sensing his greater priority was Marrakesh, where recusant Almohad sheikhs had rallied behind Yahya, another son of al-Nasir, al-Adil paid little attention to this little band of misfits.

Zayyanid Dynasty

The Kingdom of Tlemcen or Zayyanid Kingdom of Tlemcen (Arabic: الزيانيون) was a Berber[138][139] kingdom in what is now the northwest of Algeria. Its territory stretched from Tlemcen to the Chelif bend and Algiers, and at its zenith reached Sijilmasa and the Moulouya River in the west, Tuat to the south and the Soummam in the east.[140][141][142]

The Tlemcen Kingdom was established after the demise of the Almohad Caliphate in 1236, and later fell under Ottoman rule in 1554. It was ruled by sultans of the Zayyanid dynasty. The capital of the Tlemcen kingdom centred on Tlemcen, which lay on the primary east–west route between Morocco and Ifriqiya. The kingdom was situated between the realm of the Marinids the west, centred on Fez, and the Hafsids to the east, centred on Tunis.

Tlemcen was a hub for the north–south trade route from Oran on the Mediterranean coast to the Western Sudan. As a prosperous trading centre, it attracted its more powerful neighbours. At different times the kingdom was invaded and occupied by the Marinids from the west,[143] by the Hafsids from the east, and by Aragonese from the north. At other times, they were able to take advantage of turmoil among their neighbours: during the reign of Abu Tashfin I (r. 1318–1337) the Zayyanids occupied Tunis and in 1423, under the reign of Abu Malek, they briefly captured Fez.[144][145]: 287 In the south the Zayyanid realm included Tuat, Tamentit and the Draa region which was governed by Abdallah Ibn Moslem ez Zerdali, a sheikh of the Zayyanids.[146][147][140]

Rise to power (13th century)

The Bānu ʿabd āl-Wād, also called the Bānu Ziyān or Zayyanids after Yaghmurasen Ibn Zyan, the founder of the dynasty, were leaders of a Berber group who had long been settled in the Central Maghreb. Although contemporary chroniclers asserted that they had a noble Arab origin, he reportedly spoke in Zenati dialect and denied the lineage that genealogists had attributed to him.[148][149][150] The town of Tlemcen, called Pomaria by the Romans, is about 806m above sea level in fertile, well-watered country.[151]

Tlemcen was an important centre under the Almoravid dynasty and its successors the Almohad Caliphate, who began a new wall around the town in 1161.[152]

Yaghmurasen ibn Zayyan (1235–83) of the Bānu ʿabd āl-Wād was governor of Tlemcen under the Almohads.[153] He inherited leadership of the family from his brother in 1235.[154] When the Almohad empire began to fall apart, in 1235, Yaghmurasen declared his independence.[153] The city of Tlemcen became the capital of one of three successor states, ruled for centuries by successive Ziyyanid sultans.[155] Its flag was a white crescent pointing upwards on a blue field.[156] The kingdom covered the less fertile regions of the Tell Atlas. Its people included a minority of settled farmers and villagers, and a majority of nomadic herders.[153]

Yaghmurasen was able to maintain control over the rival Berber groups, and when faced with the outside threat of the Marinid dynasty, he formed an alliance with the Emir of Granada and the King of Castile, Alfonso X.[157] According to Ibn Khaldun, "he was the bravest, most dreaded and honourable man of the 'Abd-la-Wadid family. No one looked after the interest of his people, maintained the influence of the kingdom and managed the state administration better than he did."[154] In 1248 he defeated the Almohad Caliph in the Battle of Oujda during which the Almohad Caliph was killed. In 1264 he managed to conquer Sijilmasa, therefore bringing Sijilmasa and Tlemcen, the two most important outlets for trans-Saharan trade under one authority.[158][159] Sijilmasa remained under his control for 11 years.[160] Before his death he instructed his son and heir Uthman to remain on the defensive with the Marinid kingdom, but to expand into Hafsid territory if possible.[154]

14th century

For most of its history the kingdom was on the defensive, threatened by stronger states to the east and the west. The nomadic Arabs to the south also took advantage of the frequent periods of weakness to raid the centre and take control of pastures in the south.

The city of Tlemcen was several times attacked or besieged by the Marinids, and large parts of the kingdom were occupied by them for several decades in the fourteenth century.[153]

The Marinid Abu Yaqub Yusuf an-Nasr besieged Tlemcen from 1299 to 1307. During the siege he built a new town, al-Mansura, diverting most of the trade to this town.[162] The new city was fortified and had a mosque, baths and palaces. The siege was raised when Abu Yakub was murdered in his sleep by one of his eunuchs.[144]

When the Marinids left in 1307, the Zayyanids promptly destroyed al-Mansura.[162] The Zayyanid king Abu Zayyan I died in 1308 and was succeeded by Abu Hammu I (r. 1308–1318). Abu Hammu was later killed in a conspiracy instigated by his son and heir Abu Tashufin I (r. 1318–1337). The reigns of Abu Hammu I and Abu Tashufin I marked the second apogee of the Zayyanids, a period during which they consolidated their hegemony in the central Maghreb.[160] Tlemcen recovered its trade and its population grew, reaching about 100,000 by around the 1330s.[162] Abu Tashufin initiated hostilities against Ifriqiya while the Marinids were distracted by their internal struggles. He besieged Béjaïa and sent an army into Tunisia that defeated the Hafsid king Abu Yahya Abu Bakr II, who fled to Constantine while the Zayyanids occupied Tunis in 1325.[144][163][164]

The Marinid sultan Abu al-Hasan (r. 1331–1348) cemented an alliance with Hafsids by marrying a Hafsid princess. Upon being attacked by the Zayyanids again, the Hafsids appealed to Abu al-Hasan for help, providing him with an excuse to invade his neighbour.[165] The Marinid sultan initiated a siege of Tlemcen in 1335 and the city fell in 1337.[162] Abu Tashufin died during the fighting.[144] Abu al-Hasan received delegates from Egypt, Granada, Tunis and Mali congratulating him on his victory, by which he had gained complete control of the trans-Saharan trade.[165] In 1346 the Hafsid Sultan, Abu Bakr, died and a dispute over the succession ensued. In 1347 Abu al-Hasan annexed Ifriqiya, briefly reuniting the Maghrib territories as they had been under the Almohads.[166]

However, Abu al-Hasan went too far in attempting to impose more authority over the Arab tribes, who revolted and in April 1348 defeated his army near Kairouan. His son, Abu Inan Faris, who had been serving as governor of Tlemcen, returned to Fez and declared that he was sultan. Tlemcen and the central Maghreb revolted.[166] The Zayyanid Abu Thabit I (1348-1352) was proclaimed king of Tlemcen.[144] Abu al-Hasan had to return from Ifriqiya by sea. After failing to retake Tlemcen and being defeated by his son, Abu al-Hasan died in May 1351.[166] In 1352 Abu Inan Faris recaptured Tlemcen. He also reconquered the central Maghreb. He took Béjaïa in 1353 and Tunis in 1357, becoming master of Ifriqiya. In 1358 he was forced to return to Fez due to Arab opposition, where he fell sick and was killed.[166]

The Zayyanid king Abu Hammu Musa II (r. 1359–1389) next took the throne of Tlemcen. He pursued an expansionist policy, pushing towards Fez in the west and into the Chelif valley and Béjaïa in the east.[153] He had a long reign punctuated by fighting against the Marinids or various rebel groups.[144] The Marinids reoccupied Tlemcen in 1360 and in 1370.[141] In both cases, the Marinids found they were unable to hold the region against local resistance.[167] Abu Hammu attacked the Hafsids in Béjaïa again in 1366, but this resulted in Hafsid intervention in the kingdom's affairs. The Hafsid sultan released Abu Hammu's cousin, Abu Zayyan, and helped him in laying claim to the Zayyanid throne. This provoked an internecine war between the two Zayyanids until 1378, when Abu Hammu finally captured Abu Zayyan in Algiers.[168]

The historian Ibn Khaldun lived in Tlemcen for a period during the generally prosperous reign of Abu Hammu Musa II, and helped him in negotiations with the nomadic Arabs. He said of this period, "Here [in Tlemcen] science and arts developed with success; here were born scholars and outstanding men, whose glory penetrated into other countries." Abu Hammu was deposed by his son, Abu Tashfin II (1389–94), and the state went into decline.[169]

Decline (late 14th and 15th centuries)

In the late 14th century and the 15th century, the state was increasingly weak and became intermittently a vassal of Hafsid Ifriqiya, Marinid Morocco or the Crown of Aragon.[170] In 1386 Abu Hammu moved his capital to Algiers, which he judged less vulnerable, but a year later his son, Abu Tashufin, overthrew him and took him prisoner. Abu Hammu was sent on a ship towards Alexandria but he escaped along the way when the ship stopped in Tunis. In 1388 he recaptured Tlemcen, forcing his son to flee. Abu Tashufin sought refuge in Fez and enlisted the aid of the Marinids, who sent an army to occupy Tlemcen and reinstall him on the throne. As a result, Abu Tashufin and his successors recognized the suzerainty of the Marinids and paid them an annual tribute.[168]

During the reign of the Marinid sultan Abu Sa'id, the Zayyanids rebelled on several occasions and Abu Sa'id had to reassert his authority.[171]: 33–39 After Abu Sa'id's death in 1420 the Marinids were plunged into political turmoil. The Zayyanid emir, Abu Malek, used this opportunity to throw off Marinid authority and captured Fez in 1423. Abu Malek installed Muhammad, a Marinid prince, as a Zayyanid vassal in Fez.[145]: 287 [171]: 47–49 The Wattasids, a family related to the Marinids, continued to govern from Salé, where they proclaimed Abd al-Haqq II, an infant, as the successor to the Marinid throne, with Abu Zakariyya al-Wattasi as regent. The Hafsid sultan, Abd al-Aziz II, reacted to Abu Malek's rising influence by sending military expeditions westward, installing his own Zayyanid client king (Abu Abdallah II) in Tlemcen and pursuing Abu Malek to Fez. Abu Malek's Marinid puppet, Muhammad, was deposed and the Wattasids returned with Abd al-Haqq II to Fez, acknowledging Hafsid suzerainty.[145]: 287 [171]: 47–49 The Zayyanids remained vassals of the Hafsids until the end of the 15th century, when the Spanish expansion along the coast weakened the rule of both dynasties.[168]

By the end of the 15th century the Kingdom of Aragon had gained effective political control, intervening in the dynastic disputes of the amirs of Tlemcen, whose authority had shrunk to the town and its immediate neighbourship.[169] When the Spanish took the city of Oran from the kingdom in 1509, continuous pressure from the Berbers prompted the Spanish to attempt a counterattack against the city of Tlemcen (1543), which was deemed by the Papacy to be a crusade. The Spanish under Martin of Angulo had also suffered a prior defeat in 1535 when they attempted to install a client ruler in Tlemcen. The Spanish failed to take the city in the first attack, but the strategic vulnerability of Tlemcen caused the kingdom's weight to shift toward the safer and more heavily fortified corsair base at Algiers.

Tlemcen was captured in 1551 by the Ottoman Empire under Hassan Pasha. The last Zayyanid sultan's son escaped to Oran, then a Spanish possession. He was baptized and lived a quiet life as Don Carlos at the court of Philip II of Spain.[citation needed]

Under the Ottoman Empire Tlemcen quickly lost its former importance, becoming a sleepy provincial town.[172] The failure of the kingdom to become a powerful state can be explained by the lack of geographical or cultural unity, the constant internal disputes and the reliance on irregular Arab-Berber nomads for the military.[138]

Kingdom of Beni Abbas

Kingdom of Kuku

Christian conquest of Spain

The final triumph of the 700-year Christian conquest of Spain was marked by the fall of Granada in 1492. Christian Spain imposed its influence on the Maghrib coast by constructing fortified outposts and collecting tribute. But Spain never sought to extend its North African conquests much beyond a few modest enclaves. Privateering was an age-old practice in the Mediterranean, and North African rulers engaged in it increasingly in the late 16th and early 17th centuries because it was so lucrative. Until the 17th century the Barbary pirates used galleys, but a Dutch renegade of the name of Zymen Danseker taught them the advantage of using sailing ships.[173]

Algeria became the privateering city-state par excellence, and two privateer brothers were instrumental in extending Ottoman influence in Algeria. At about the time Spain was establishing its presidios in the Maghrib, the Muslim privateer brothers Aruj and Khair ad Din—the latter known to Europeans as Barbarossa, or Red Beard—were operating successfully off Tunisia. In 1516 Aruj moved his base of operations to Algiers but was killed in 1518. Khair ad Din succeeded him as military commander of Algiers, and the Ottoman sultan gave him the title of beglerbey (provincial governor).

Spanish enclaves

The Spanish expansionist policy in North Africa began with the Catholic Monarchs and the regent Cisneros, once the Reconquista in the Iberian Peninsula was finished. That way, several towns and outposts in the Algerian coast were conquered and occupied: Mers El Kébir (1505), Oran (1509), Algiers (1510) and Bugia (1510). The Spanish conquest of Oran was won with much bloodshed: 4,000 Algerians were massacred, and up to 8,000 were taken prisoner. For about 200 years, Oran's inhabitants were virtually held captive in their fortress walls, ravaged by famine and plague; Spanish soldiers, too, were irregularly fed and paid.[174]

The Spaniards left Algiers in 1529, Bujia in 1554, Mers El Kébir and Oran in 1708. The Spanish returned in 1732 when the armada of the Duke of Montemar was victorious in the Battle of Aïn-el-Turk and retook Oran and Mers El Kébir; the Spanish massacred many Muslim soldiers.[175] In 1751, a Spanish adventurer, named John Gascon, obtained permission, and vessels and fireworks, to go against Algiers, and set fire, at night, to the Algerian fleet. The plan, however, miscarried. In 1775, Charles III of Spain sent a large force to attack Algiers, under the command of Alejandro O'Reilly (who had led Spanish forces in crushing French rebellion in Louisiana), resulting in a disastrous defeat. The Algerians suffered 5,000 casualties.[176] The Spanish navy bombarded Algiers in 1784; over 20,000 cannonballs were fired, much of the city and its fortifications were destroyed and most of the Algerian fleet was sunk.[177]

Oran and Mers El Kébir were held until 1792, when they were sold by the king Charles IV to the Bey of Algiers.

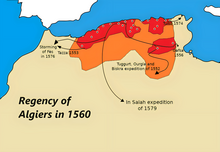

Regency of Algiers

The Regency of Algiers[c] (Arabic: دولة الجزائر, romanized: Dawlat al-Jaza'ir[d]) was a state in North Africa lasting from 1516 to 1830, until it was conquered by the French. Situated between the regency of Tunis in the east, the Sultanate of Morocco (from 1553) in the west and Tuat[186][187] as well as the country south of In Salah[188] in the south (and the Spanish and Portuguese possessions of North Africa), the Regency originally extended its borders from La Calle in the east to Trara in the west and from Algiers to Biskra,[189] and afterwards spread to the present eastern and western borders of Algeria.[190]

It had various degrees of autonomy throughout its existence, in some cases reaching complete independence, recognized even by the Ottoman sultan.[191] The country was initially governed by governors appointed by the Ottoman sultan (1518–1659), rulers appointed by the Odjak of Algiers (1659–1710), and then Deys elected by the Divan of Algiers from (1710-1830).

Establishment

From 1496, the Spanish conquered numerous possessions on the North African coast: Melilla (1496), Mers El Kébir (1505), Oran (1509), Bougie (1510), Tripoli (1510), Algiers, Shershell, Dellys, and Tenes.[192] The Spaniards later led unsuccessful expeditions to take Algiers in the Algiers expedition in 1516, 1519 and another failed expedition in 1541.

Around the same time, the Ottoman privateer brothers Oruç and Hayreddin—both known to Europeans as Barbarossa, or "Red Beard"—were operating successfully off Tunisia under the Hafsids. In 1516, Oruç moved his base of operations to Algiers. He asked for the protection of the Ottoman Empire in 1517, but was killed in 1518 during his invasion of the Zayyanid Kingdom of Tlemcen. Hayreddin succeeded him as military commander of Algiers.[193]

In 1551 Hasan Pasha, the son of Hayreddin defeated the Spanish-Moroccan armies during a campaign to recapture Tlemcen, thus cementing Ottoman control in western and central Algeria.[194]

After that, the conquest of Algeria sped up. In 1552 Salah Rais, with the help of some Kabyle kingdoms, conquered Touggourt, and established a foothold in the Sahara.[195]

In the 1560s eastern Algeria was centralized, and the power struggle which had been present ever since the Emirate of Béjaïa collapsed came to an end.

During the 16th, 17th, and early 18th century, the Kabyle Kingdoms of Kuku and Ait Abbas managed to maintain their independence[196][197][198] repelling Ottoman attacks several times, notably in the First Battle of Kalaa of the Beni Abbes. This was mainly thanks to their ideal position deep inside the Kabylia Mountains and their great organisation, and the fact that unlike in the West and East where collapsing kingdoms such as Tlemcen or Béjaïa were present, Kabylia had two new and energetic emirates.

Base in the war against Spain

Hayreddin Barbarossa established the military basis of the regency. The Ottomans provided a supporting garrison of 2,000 Turkish troops with artillery.[199] He left Hasan Agha in command as his deputy when he had to leave for Constantinople in 1533.[200] The son of Barbarossa, Hasan Pashan was in 1544 when his father retired, the first governor of the Regency to be directly appointed by the Ottoman Empire. He took the title of beylerbey.[200] Algiers became a base in the war against Spain, and also in the Ottoman conflicts with Morocco.

Beylerbeys continued to be nominated for unlimited tenures until 1587. After Spain had sent an embassy to Constantinople in 1578 to negotiate a truce, leading to a formal peace in August 1580, the Regency of Algiers was a formal Ottoman territory, rather than just a military base in the war against Spain.[200] At this time, the Ottoman Empire set up a regular Ottoman administration in Algiers and its dependencies, headed by Pashas, with 3-year terms to help considate Ottoman power in the Maghreb.

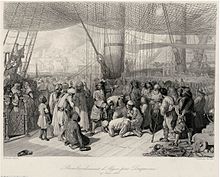

Mediterranean privateers

Despite the end of formal hostilities with Spain in 1580, attacks on Christian and especially Catholic shipping, with slavery for the captured, became prevalent in Algiers and were actually the main industry and source of revenues of the Regency.[201]

In the early 17th century, Algiers also became, along with other North African ports such as Tunis, one of the bases for Anglo-Turkish piracy. There were as many as 8,000 renegades in the city in 1634.[201][202] (Renegades were former Christians, sometimes fleeing the law, who voluntarily moved to Muslim territory and converted to Islam.) Hayreddin Barbarossa is credited with tearing down the Peñón of Algiers and using the stone to build the inner harbor.[203]

A contemporary letter states:

"The infinity of goods, merchandise jewels and treasure taken by our English pirates daily from Christians and carried to Algire and Tunis to the great enriching of Mores and Turks and impoverishing of Christians"

— Contemporary letter sent from Portugal to England.[204]

Privateers and slavery of Christians originating from Algiers were a major problem throughout the centuries, leading to regular punitive expeditions by European powers. Spain (1567, 1775, 1783), Denmark (1770), France (1661, 1665, 1682, 1683, 1688), England (1622, 1655, 1672), all led naval bombardments against Algiers.[201] Abraham Duquesne fought the Barbary pirates in 1681 and bombarded Algiers between 1682 and 1683, to help Christian captives.[205]

Political Turmoil (1659-1713)

The Agha period

In 1659 the Janissaries of the Odjak of Algiers took over the country, and removed the local Pasha with the blessing of the Ottoman Sultan. From there on a system of dual leaders was in place. There was first and foremost the Agha, elected by the Odjak, and the Pasha appointed by the Ottoman Sublime Porte, whom was a major cause of unrest.[206] Of course, this duality was not stable. All of the Aghas were assassinated, without an exception. Even the first Agha was killed after only 1 year of rule. Thanks to this the Pashas from Constantinople were able to increase the power, and reaffirm Turkish control over the region. In 1671, the Rais, the pirate captains, elected a new leader, Mohamed Trik. The Janissaries also supported him, and started calling him the Dey, which means Uncle in Turkish.[207]

Early Dey period (1671-1710)

In the early Dey period the country worked similarly to before, with the Pasha still holding considerable powers, but instead of the Janissaries electing their own leaders freely, other factions such as the Taifa of Rais also wanted to elect the deys. Mohammed Trik, taking over during a time instability was faced with heavy issues. Not only were the Janissaries on a rampage, removing any leaders for even the smallest mistakes (even if those leaders were elected by them), but the native populace was also restless. The conflicts with European powers didn't help this either. In 1677, following an explosion in Algiers and several attempts at his life, Mohammed escaped to Tripoli leaving Algiers to Baba Hassan.[208] Just 4 years into his rule he was already at war with one of the most powerful countries in Europe, the Kingdom of France. In 1682 France bombarded Algiers for the first time.[209] The Bombardment was inconclusive, and the leader of the fleet Abraham Duquesne failed to secure the submission of Algiers. The next year, Algiers was bombarded again, this time liberating a few slaves. Before a peace treaty could be signed though, Baba Hassan was deposed and killed by a Rais called Mezzo Morto Hüseyin.[210] Continuing the war against France he was defeated in a naval battle in 1685, near Cherchell, and at last a French Bombardment in 1688 brought an end to his reign, and the war. His successor, Hadj Chabane was elected by the Raïs. He defeated Morocco in the Battle of Moulouya and defeated Tunis as well.[211] He went back to Algiers, but he was assassinated in 1695 by the Janissaries whom once again took over the country. From there on Algiers was in turmoil once again. Leaders were assassinated, despite not even ruling for a year, and the Pasha was still a cause of unrest. The only notable event during this time of unrest was the recapture of Oran and Mers-el-Kébir from the Spanish.

Coup of Baba Ali Chaouche, and independence

Baba Ali Chaouche, also written as Chaouch, took over the country, ending the rule of the Janissaries. The Pasha attempted to resist him, but instead he was sent home, and told to never come back, and if he did he will be executed. He also sent a letter to the Ottoman sultan declaring that Algiers will from then on act as an independent state, and will not be an Ottoman vassal, but an ally at best.[212] The Sublime Porte, enraged, tried to send another Pasha to Algiers, whom was then sent back to Constantinople by the Algerians. This marked the de facto independence of Algiers from the Ottoman Empire.[213]

Danish–Algerian War

In the mid-1700s Dano-Norwegian trade in the Mediterranean expanded. In order to protect the lucrative business against piracy, Denmark–Norway had secured a peace deal with the states of Barbary Coast. It involved paying an annual tribute to the individual rulers and additionally to the States.

In 1766, Algiers had a new ruler, dey Baba Mohammed ben-Osman. He demanded that the annual payment made by Denmark-Norway should be increased, and he should receive new gifts. Denmark–Norway refused the demands. Shortly after, Algerian pirates hijacked three Dano-Norwegian ships and allowed the crew to be sold as slaves.

They threatened to bombard the Algerian capital if the Algerians did not agree to a new peace deal on Danish terms. Algiers was not intimidated by the fleet, the fleet was of 2 frigates, 2 bomb galiot and 4 ship of the line.

Algerian-Sharifian War

In the west, the Algerian-Cherifian conflicts shaped the western border of Algeria.[214]

There were numerous battles between the Regency of Algiers and the Sharifian Empires for example: the campaign of Tlemcen in 1551, the campaign of Tlemcen in 1557, the Battle of Moulouya and the Battle of Chelif. The independent Kabyle Kingdoms also had some involvement, the Kingdom of Beni Abbes participated in the campaign of Tlemcen in 1551 and the Kingdom of Kuku provided Zwawa troops for the capture of Fez in 1576 in which Abd al-Malik was installed as an Ottoman vassal ruler over the Saadi Dynasty.[215][216] The Kingdom of Kuku also participated in the capture of Fez in 1554 in which Salih Rais defeated the Moroccan army and conquered Morocco up until Fez, adding these territories to the Ottoman crown and placing Ali Abu Hassun as the ruler and vassal to the Ottoman sultan.[217][218][219] In 1792 the Regency of Algiers managed to take possession of the Moroccan Rif and Oujda, which they then abandoned in 1795 for unknown reasons.[220]

Barbary Wars

During the early 19th century, Algiers again resorted to widespread piracy against shipping from Europe and the young United States of America, mainly due to internal fiscal difficulties, and the damage caused by the Napoleonic Wars.[201] This in turn led to the First Barbary War and Second Barbary War, which culminated in August 1816 when Lord Exmouth executed a naval bombardment of Algiers, the biggest, and most successful one.[221] The Barbary Wars resulted in a major victory for the American, British, and Dutch Navy.

Political status

1516-1567

In between 1516 and 1567, the rulers of the Regency were chosen by the Ottoman sultan. During the first few decades, Algiers was completely aligned with the Ottoman Empire, although it later gained a certain level of autonomy as it was the westernmost province of the Ottoman Empire, and administering it directly would have been problematic.[222]

1567-1710

During this period a form of dual leadership was in place, with the Aghas sharing power and influence with a Pasha appointed by the Ottoman sultan from Constantinople.[223] After 1567, the Deys became the main leaders of the country, although the Pashas still retained some power.[224]

1710-1830

After a coup by Baba Ali Chaouch, the political situation of Algiers became complicated.

Relation with the Ottoman Empire

Some sources describe it as completely independent from the Ottomans,[225][226][227] albeit the state was still nominally part of the Ottoman Empire.[228]

Cur Abdy, dey of Algiers shouted at an Ottoman envoy for claiming that the Ottoman Padishah was the king of Algiers ("King of Algiers? King of Algiers? If he is the King of Algiers then who am I?").[229][230]

Despite the Ottomans having no influence in Algiers, and the Algerians often ignoring orders from the Ottoman sultan, such as in 1784.[191] In some cases Algiers also participated in the Ottoman Empire's wars, such as the Russo-Turkish War (1787–1792),[231] albeit this was not common, and in 1798 for example Algiers sold wheat to the French Empire campaigning in Egypt against the Ottomans through two Jewish traders.

In some cases, Algiers was declared to be a country rebelling against the holy law of Islam by the Ottoman Caliph.[232] This usually meant a declaration of war by the Ottomans against the Deylik of Algiers.[232] This could happen due to many reasons. For example, under the rule of Haji Ali Dey, Algerian pirates regularly attacked Ottoman shipments, and Algiers waged war against the Beylik of Tunis,[233] despite several protests by the Ottoman Porte, which resulted in a declaration of war.