Covenanters

Covenanters[a] were members of a 17th-century Scottish religious and political movement, who supported a Presbyterian Church of Scotland and the primacy of its leaders in religious affairs. It originated in disputes with James VI and his son Charles I over church organisation and doctrine, but expanded into political conflict over the limits of royal authority.

In 1638, thousands of Scots signed the National Covenant, pledging to resist changes in religious practice imposed by Charles. This led to the 1639 and 1640 Bishops' Wars, which ended with the Covenanters in control of the Scottish government. In response to the Irish Rebellion of 1641, Covenanter troops were sent to Ireland, and the 1643 Solemn League and Covenant brought them into the First English Civil War on the side of Parliament.

As the Wars of the Three Kingdoms progressed, many Covenanters came to view English religious Independents like Oliver Cromwell as a greater threat than the Royalists, particularly their opposition to state religion. During the 1648 Second English Civil War, a Covenanter faction known as Engagers allied with Scots and English Royalists. A Scottish army invaded England, but were defeated. The Kirk Party now gained political power, and in 1650, agreed to provide Charles II with Scottish military support to regain the English throne, then crowned him King of Britain in 1651. Scotland lost the subsequent Anglo-Scottish War of 1650 to 1652 and was absorbed into the Commonwealth of England. The Kirk lost its position as the state church, and the rulings of its assemblies were no longer enforced by law.

Following the 1660 Stuart Restoration, the Parliament of Scotland passed laws reversing reforms enacted since 1639. Bishops were restored to the Kirk, while ministers and other officeholders were obliged to take the Oath of Abjuration rejecting the 1638 Covenant. As a result, many Covenanters opposed the new regime, leading to a series of plots and armed rebellions. After the 1688 Glorious Revolution in Scotland, the Church of Scotland was re-established as a wholly Presbyterian structure and most Covenanters readmitted. Dissident minorities persisted in Scotland, Ireland, and North America, which continue today as the Reformed Presbyterian Global Alliance.

Background

The 16th century Scottish Reformation resulted in the creation of a reformed Church of Scotland, informally known as the Kirk, which was Presbyterian in structure, and Calvinist in doctrine. In December 1557, it became the state church of Scotland, and in 1560, the Parliament of Scotland adopted the Scots Confession which rejected many Catholic teachings and practices.[1]

The Confession was adopted by James VI, and re-affirmed first in 1590, then in 1596. However, James argued that as king, he was also head of the church, governing through bishops appointed by himself. [2] [b] When James became king of England in 1603, he saw a unified Church of England and Scotland as the first step in creating a centralised, unionist state.[5] Although both churches shared much of the same doctrine, even Scottish bishops rejected many Church of England practices as little better than Catholic.[6]

By 1630, Catholicism was largely confined to the aristocracy and remote, Gaelic-speaking areas of the Highlands and Islands but opposition to it remained widespread in Scotland.[7] Many Scots fought in the Thirty Years' War, one of the most destructive religious conflicts in European history, while there were close economic and cultural with the Protestant Dutch Republic, then fighting for independence from Catholic Spain. Lastly, the majority of kirk ministers had been educated in French Calvinist universities, most of which were suppressed in the Huguenot rebellions of the 1620s.[8]

These links, combined with a general perception that Protestant Europe was under attack, meant heightened sensitivity around religious practice. In 1636, Charles I replaced the existing Scottish Book of Discipline with a new Book of Canons, and excommunicated anyone who denied Royal supremacy in church matters.[9] When a revised Book of Common Prayer was introduced in 1637, it caused anger and widespread rioting across Scotland, perhaps the most famous sparked when Jenny Geddes threw a stool at the minister in St Giles Cathedral.[10] More recently, historians like Mark Kishlansky have argued she was part of a series of carefully planned and co-ordinated acts of protest, the origin being as much political as it was religious.[11]

Wars of the Three Kingdoms

Supervised by Archibald Johnston and Alexander Henderson, in February 1638 representatives from all sections of Scottish society agreed to a National Covenant, pledging resistance to liturgical "innovations". Covenanters believed they were preserving a divinely ordained form of religion which Charles was seeking to alter, although debate as to what exactly that meant persisted until finally settled in 1690.[12] While the National Covenant said nothing about bishops, they were expelled from the kirk when the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland met in Glasgow in December 1638.[13]

Support for the Covenant was widespread except in Aberdeenshire and Banff, centre of Episcopalian resistance for the next 60 years.[14] The Marquess of Argyll and six other members of the Scottish Privy Council had backed the Covenant;[15] Charles tried to impose his authority in the 1639 and 1640 Bishop's Wars, with his defeat leaving the Covenanters in control of Scotland.[16] When the First English Civil War began in 1642, the Scots remained neutral at first but sent troops to Ulster to support their co-religionists in the Irish Rebellion; the bitterness of this conflict radicalised views in Scotland and Ireland.[17]

Since Calvinists believed a "well-ordered" monarchy was part of God's plan, the Covenanters committed to "defend the king's person and authority with our goods, bodies, and lives". The idea of government without a king was inconceivable.[18] This view was generally shared by English Parliamentarians, who wanted to control Charles, not remove him, but both they and their Royalist opponents were further divided over religious doctrine. In Scotland, near unanimous agreement on doctrine meant differences centred on who held ultimate authority in clerical affairs. Royalists tended to be "traditionalist" in religion and politics but there were various factors, including nationalist allegiance to the Kirk. Individual motives were very complex, and many fought on both sides, including Montrose, a Covenanter general in 1639 and 1640 who nearly restored Royalist rule in Scotland in 1645.[19]

The Covenanter faction led by Argyll saw religious union with England as the best way to preserve a Presbyterian Kirk and in October 1643, the Solemn League and Covenant agreed a Presbyterian Union in return for Scottish military support.[20] Royalists and moderates in both Scotland and England opposed this on nationalist grounds, while religious Independents like Oliver Cromwell claimed he would fight, rather than agree to it.[21]

The Covenanters and their English Presbyterian allies gradually came to see the Independents who dominated the New Model Army as a bigger threat than the Royalists and when Charles surrendered in 1646, they began negotiations to restore him to the English throne. In December 1647, Charles agreed to impose Presbyterianism in England for three years and suppress the Independents but his refusal to take the Covenant himself split the Covenanters into Engagers and Kirk Party fundamentalists or Whiggamores. Defeat in the Second English Civil War resulted in the execution of Charles in January 1649 and the Kirk Party taking control of the General Assembly.[22]

In February 1649, the Scots proclaimed Charles II "King of Great Britain".[23] Under the terms of the Treaty of Breda, the Kirk Party agreed to restore him to the English throne and in return he accepted the Covenant. Defeats at Dunbar and Worcester resulted with Scotland being incorporated into the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland in 1652.[24]

Under the Commonwealth

After defeat in 1651, the Covenanters split into two factions. Over two-thirds of the ministry supported the Resolution of December 1650 re-admitting Royalists and Engagers and were known as "Resolutioners". "Protestors" were largely former Kirk Party fundamentalists or Whiggamores who blamed defeat on compromise with "malignants". Differences between the two were both religious and political, including church government, religious toleration and the role of law in a godly society.[25]

Following the events of 1648–51, Cromwell decided the only way forward was to eliminate the power of the Scottish landed elite and the Kirk. The Terms of Incorporation published on 12 February 1652 made a new Council of Scotland responsible for regulating church affairs and allowed freedom of worship for all Protestant sects. Since Presbyterianism was no longer the state religion, kirk sessions and synods functioned as before but its edicts were not enforced by civil penalties.[26]

Covenanters were hostile to sects like the Congregationalists and Quakers because they advocated separation of church and state. Apart from a small number of Protestors known as Separatists, the vast majority refused to accept these changes, and Scotland was incorporated into the Commonwealth without further consultation on 21 April 1652.[27]

Contests for control of individual presbyteries made the split increasingly bitter and in July 1653 each faction held its own General Assembly in Edinburgh. Robert Lilburne, English military commander in Scotland, used the excuse of Resolutioner church services praying for the success of Glencairn's rising to dissolve both sessions. The Assembly would not formally reconvene until 1690, the Resolutioner majority instead meeting in informal "Consultations" and Protestors holding field assemblies or conventicles outside Resolutioner-controlled kirk structures.[28]

When the Protectorate was established in 1654, Lord Broghill, head of the Council of State for Scotland summarised his dilemma; "the Resolutioners love Charles Stuart and hate us, while the Protesters love neither him nor us."[29] Neither side was willing to co-operate with the Protectorate except in Glasgow, where Protestors led by Patrick Gillespie used the authorities in their contest with local Resolutioners.[30]

Since the Resolutioners controlled 750 of 900 parishes, Broghill recognised they could not be ignored; his policy was to isolate the "extreme" elements of both factions, hoping to create a new, moderate majority.[31] He therefore encouraged internal divisions within the Kirk, including appointing Gillespie Principal of the University of Glasgow, against the wishes of the James Guthrie and Warriston-led Protestor majority. The Protectorate authorities effectively became arbitrators between the factions, each of whom appointed representatives to argue their case in London; the repercussions affected the Kirk for decades to come.[32]

Restoration settlement

After the Restoration of the Monarchy in 1660, Scotland regained control of the Kirk, but the Rescissory Act 1661 restored the legal position of 1633 and removing the Covenanter reforms of 1638–1639. The Privy Council of Scotland restored bishops on 6 September 1661. James Sharp, leader of the Resolutioners, became Archbishop of St Andrews; Robert Leighton was consecrated Bishop of Dunblane, and soon an entire bench of bishops had been appointed.[33]

In 1662, the Kirk was restored as the national church, independent sects banned and all office-holders required to renounce the 1638 Covenant; about a third, or around 270 in total, refused to do so and lost their positions as a result.[33] Most occurred in the south-west of Scotland, an area particularly strong in its Covenanting sympathies; the practice of holding conventicles outside the formal structure continued, often attracting thousands of worshippers.[34]

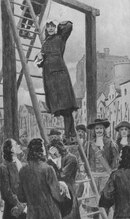

The government alternated between persecution and toleration; in 1663, it declared dissenting ministers "seditious persons" and imposed heavy fines on those who failed to attend the parish churches of the "King's curates". In 1666, a group of men from Galloway captured the local military commander, marched on Edinburgh and were defeated at the Battle of Rullion Green. Around 50 prisoners were taken, while a number of others were arrested; 33 were executed and the rest transported to Barbados.[35]

The Rising led to the replacement of the Duke of Rothes as King's Commissioner by John Maitland, 1st Duke of Lauderdale who followed a more conciliatory policy. Letters of Indulgence were issued in 1669, 1672 and 1679, allowing evicted ministers to return to their parishes, if they agreed to avoid politics. A number returned but over 150 refused the offer, while many Episcopalians were alienated by the compromise.[36]

The outcome was a return to persecution; preaching at a conventicle was made punishable by death, while attendance attracted severe sanctions. In 1674, heritors and masters were made responsible for the "good behaviour" of their tenants and servants; from 1677, this meant posting bonds for those living on their land. In 1678, 3,000 Lowland militia and 6,000 Highlanders, known as the "Highland Host", were billeted in the Covenanting shires, especially those in the South-West, as a form of punishment.[37]

1679 rebellion and the Killing Time

The assassination of Archbishop Sharp by Covenanter radicals in May 1679 led to a revolt that ended at the Battle of Bothwell Bridge in June. Although battlefield casualties were relatively few, over 1,200 prisoners were sentenced to transportation, the chief prosecutor being Lord Advocate Rosehaugh.[38] Claims of undocumented, indiscriminate killing in the aftermath of the battle have also been made.[39]

Defeat split the movement into moderates and extremists, the latter headed by Donald Cargill and Richard Cameron who issued the Sanquhar Declaration in June 1680. While Covenanters previously claimed to object only to state religious policy, this renounced any allegiance to either Charles, or his Catholic brother James. Adherents were known as Cameronians, and although a relatively small minority, the deaths of Cameron, his brother and Cargill gained them considerable sympathy.[40]

The 1681 Scottish Succession and Test Acts made obedience to the monarch a legal obligation, "regardless of religion", but in return confirmed the primacy of the Kirk "as currently constituted". This excluded the Covenanters, who wanted to restore it to the structure prevailing in 1640.[41] A number of government figures, including James Dalrymple, chief legal officer, and Archibald Campbell, 9th Earl of Argyll, objected to inconsistencies in the Act and refused to swear.[c] Argyll was convicted of treason and sentenced to death, although he and Dalrymple escaped to the Dutch Republic.[43]

The Cameronians were now organised more formally as the United Societies; estimates of their numbers vary from 6,000 to 7,000, mostly concentrated in Argyllshire.[44] Led by James Renwick, in 1684 copies of an Apologetical Declaration were posted in different locations, effectively declaring war on government officers. This led to the period known in Protestant historiography as "the Killing Time"; the Scottish Privy Council authorised the extrajudicial execution of any Covenanters caught in arms, policies carried out by troops under John Graham, 1st Viscount Dundee.[45] At the same time, Lord Rosehaugh adopted the French practice of same day trial and execution for militants who refused to swear oaths of loyalty to the king.[46]

Despite his Catholicism, James VII became king in April 1685 with widespread support, largely due to fears of civil war if he were bypassed, and opposition to re-opening past divisions within the Kirk.[47] These factors contributed to the rapid defeat of Argyll's Rising in June 1685; in a bid to widen its appeal, his manifesto omitted any mention of the 1638 Covenant. Renwick and his followers refused to support it as a result.[48]

The Glorious Revolution and the 1690 settlement

A major factor in the defeat of Argyll's Rising was the desire for stability within the Kirk. By issuing Letters of Indulgence to dissident Presbyterians in 1687, James now threatened to re-open this debate and undermine his own Episcopalian base. At the same time, he excluded the Society People, and created another Covenanter martyr with the execution of Renwick in February 1688.[49]

In June 1688, two events turned dissent into a crisis: the birth of James Francis Edward on 10 June created a Catholic heir, excluding James' Protestant daughter Mary and her husband William of Orange. Prosecuting the Seven Bishops seemed to go beyond tolerance for Catholicism and into an assault on the Episcopalian establishment; their acquittal on 30 June destroyed James' political authority.[50] Representatives from the English political class invited William to assume the English throne; when he landed in Brixham on 5 November, James' army deserted him and he left for France on 23 December.[51]

The Scottish Convention elected in March to determine settlement of the Scottish throne was dominated by Covenanter sympathisers. On 4 April, it passed the Claim of Right and the "Articles of Grievances", which held James forfeited the Crown by his actions; on 11 May, William and Mary became co-monarchs of Scotland. Although William wanted to retain bishops, the role played by Covenanters during the Jacobite rising of 1689, including the Cameronians' defence of Dunkeld in August, meant their views prevailed in the political settlement that followed. The General Assembly met in November 1690 for the first time since 1654; even before it convened, over 200 Episcopalian ministers had been removed from their livings.[52]

The Assembly once again eliminated episcopacy and created two commissions for the south and north of the Tay, which over the next 25 years removed almost two-thirds of all ministers.[53] To offset this, nearly one hundred clergy returned to the Kirk in the 1693 and 1695 Acts of Indulgence, while others were protected by the local gentry and retained their positions until death by natural causes.[54]

Following the 1690 settlement, a small minority of the United Societies followed Cameronian leader Robert Hamilton in refusing to re-enter the Kirk.[55] They continued as an informal grouping until 1706, when John M'Millan was appointed minister; in 1743, he and Thomas Nairn set up the Reformed Presbyterian Church of Scotland.[56] Although the church still exists, the vast majority of its members joined the Free Church of Scotland in 1876.[54]

Legacy

Memorials

Covenanter graves and memorials from the "Killing Time" became important in perpetuating a political message, initially by the small minority of the United Societies who remained outside the Kirk. In 1701, their Assembly undertook to recover or mark the graves of the dead; many were to be found in remote places, as the government of the time deliberately sought to avoid creating places of pilgrimage.[57]

Old Mortality, an 1816 novel by Sir Walter Scott, features a character who spends his time travelling around Scotland, renewing inscriptions on Covenanter graves. In 1966, the Scottish Covenanter Memorial Association was established, which maintains these monuments throughout Scotland. One of the most famous is that erected at Greyfriars Kirkyard in 1707, commemorating 18,000 martyrs killed from 1661 to 1680.[58]

In 1721 and 1722, Robert Wodrow published The History of the Sufferings of the Church of Scotland from the Restoration to the Revolution, detailing the persecution of the Covenanter movement from 1660 to 1690. This work would be brought forward again when elements in the Church of Scotland felt it to be suffering state interference, as at the Disruption of 1843.[59]

Covenanters in North America

Throughout the 17th century, Covenanter congregations were established in Ireland, primarily in Ulster; for a variety of reasons, many subsequently migrated to North America. In 1717, William Tennent moved with his family to Philadelphia, where he later founded Log College, the first Presbyterian seminary in North America.[60]

In North America, many former Covenanters joined the Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America, which was founded in 1743.[61]

See also

- Presbyterianism

- Calvinism

- Cameronians

- Reformed Presbyterian Global Alliance

- Solemn League and Covenant

- Free Presbyterian Church of Scotland

Notes

- ^ Scottish Gaelic: Cùmhnantaich

- ^ James summarised this as "No bishops, no King"; the alternative view was best expressed by Andrew Melville as "Thair is twa Kings and twa Kingdomes in Scotland ... Chryst Jesus the King and this Kingdome the Kirk, whose subject King James the Saxt is";[3] the Kirk was subject only to God, and its members, including James, ruled by presbyteries, consisting of ministers and elders.[4]

- ^ Poorly written, it seemed to require office holders to confirm both Jesus and the reigning monarch were head of the kirk.[42]

References

- ^ Wormald 2018, pp. 120–121.

- ^ Lee 1974, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Melville 1842, p. 370.

- ^ "Our Structure". ChurchofScotland.org.uk. Church of Scotland. 22 February 2010. Retrieved 25 August 2020.

- ^ Stephen 2010, pp. 55–58.

- ^ McDonald 1998, pp. 75–76.

- ^ Fissel 1994, pp. 269, 278.

- ^ Wilson 2009, pp. 787–778.

- ^ Stevenson 1973, pp. 45–46.

- ^ Mackie, Lenman & Parker 1986, p. 203.

- ^ Kishlansky 2005, pp. 43–50.

- ^ Mackie, Lenman & Parker 1986, p. 204.

- ^ Harris 2014, p. 372.

- ^ Plant 2010.

- ^ Mackie, Lenman & Parker 1986, pp. 205–206.

- ^ Mackie, Lenman & Parker 1986, pp. 209–210.

- ^ Royle 2004, p. 142.

- ^ Macleod 2009, pp. 5–19 passim.

- ^ Harris 2014, pp. 53–54.

- ^ Robertson 2014, p. 125.

- ^ Rees 2016, pp. 118–119.

- ^ Mitchison, Fry & Fry 2002, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Royle 2004, p. 517.

- ^ Royle 2004, p. 612.

- ^ Holfelder 1998, p. 9.

- ^ Morrill 1990, p. 162.

- ^ Baker 2009, pp. 290–291.

- ^ Holfelder 1998, pp. 190–192.

- ^ Dow 1979, p. 192.

- ^ Holfelder 1998, p. 196.

- ^ Dow 1979, p. 204.

- ^ Holfelder 1998, p. 213.

- ^ a b Mackie, Lenman & Parker 1986, pp. 231–234.

- ^ Mitchison, Fry & Fry 2002, p. 253.

- ^ Mackie, Lenman & Parker 1986, pp. 235–236.

- ^ Mackie, Lenman & Parker 1986, p. 236.

- ^ Mackie, Lenman & Parker 1986, pp. 237–238.

- ^ Kennedy 2014, pp. 220–221.

- ^ M'Crie 1875, p. 331.

- ^ Christie 2008, p. 113.

- ^ Harris 2007, pp. 153–157.

- ^ Harris 2007, p. 73.

- ^ Webb 1999, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Christie 2008, p. 146.

- ^ Mackie, Lenman & Parker 1986, pp. 240–245.

- ^ Jardine 2017.

- ^ Womersley 2015, p. 189.

- ^ De Krey 2007, p. 227.

- ^ Christie 2008, p. 160.

- ^ Harris 2007, pp. 235–236.

- ^ Harris 2007, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Mackie, Lenman & Parker 1986, pp. 241–245.

- ^ Mackie, Lenman & Parker 1986, p. 246.

- ^ a b Mackie, Lenman & Parker 1986, p. 253.

- ^ Christie 2008, p. 250.

- ^ McMillan 1950, pp. 141–153.

- ^ Wallace 2017.

- ^ SCMA.

- ^ Wodrow.

- ^ EPH.

- ^ RPCNA.

Sources

- Baker, Derek (2009). Schism, Heresy and Religious Protest. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521101783.

- Christie, David (2008). Bible and Sword; the Cameronian contribution to freedom of religion (PHD). University of Stellenbosch. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Currie, Janette (2009). History, hagiography, and fakestory: representations of the Scottish Covenanters in non-fictional and fictional texts from 1638 to 1835 (PHD). University of Stirling.

- De Krey, Gary S. (2007). Restoration and Revolution in Britain. Palgrave. ISBN 978-0333651049.

- Dow, F D (1979). Cromwellian Scotland 1651–1660. John Donald. ISBN 978-0859765107.

- "Log College". ExplorePAHistory.com. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Erskine, Caroline (2009). "Participants in the Pentland rising". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/98249. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Fissel, Mark (1994). The Bishops' Wars: Charles I's Campaigns against Scotland, 1638–1640. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521466865.

- Furgol, E. M. (1983). The religious aspects of the Scottish Covenanting armies, 1639–51 (PHD). University of Oxford.[permanent dead link]

- Harris, Tim (2014). Rebellion: Britain's First Stuart Kings, 1567–1642. OUP. ISBN 978-0199209002.

- Harris, Tim (2007). Revolution; the Great Crisis of the British Monarchy 1685–1720. Penguin. ISBN 978-0141016528.

- Holfelder, Kyle (1998). Factionalism in the Kirk during the Cromwellian Invasion and Occupation of Scotland, 1650 to 1660: The Protester-Resolutioner Controversy (PHD). University of Edinburgh.

- Jardine, Mark (17 December 2017). "The Execution of Richard Rumbold in Edinburgh, 1685". History of the Covenanters. Retrieved 5 August 2020.

- Kennedy, Allan (2014). Governing Gaeldom: The Scottish Highlands and the Restoration State, 1660–1688. Brill.

- Kishlansky, Mark (2005). "Charles I: A Case of Mistaken Identity". Past and Present (189): 41–80. doi:10.1093/pastj/gti027. JSTOR 3600749.

- Lee, Maurice (1974). "James VI and the Revival of Episcopacy in Scotland: 1596–1600". Church History. 43 (1): 50–64. doi:10.2307/3164080. JSTOR 3164080. S2CID 154647179.

- Mackie, J. D.; Lenman, Bruce; Parker, Geoffrey (1986). A History of Scotland. Hippocrene Books. ISBN 978-0880290401.

- Macleod, Donald (2009). "The influence of Calvinism on politics". Theology in Scotland. XVI (2).

- Main, David. "The Origins of the Scottish Episcopal Church". St Ninians Castle Douglas. Archived from the original on 7 April 2019. Retrieved 17 July 2020.

- M'Crie, Thomas (1875). The story of the Scottish church:from the Reformation to the Disruption. Blackie & Son.

- McDonald, Alan (1998). The Jacobean Kirk, 1567–1625: Sovereignty, Polity and Liturgy. Routledge. ISBN 185928373X.

- McMillan, William (1950). "The Covenanters after the Revolution of 1688". Scottish Church History Society. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- Melville, James (1842). Pitcairn, Robert (ed.). The Autobiography and Diary of Mr. James Melville, with a Continuation of the Diary (2015 ed.). Arkose Press. ISBN 1343621844.

- Mitchison, Rosalind; Fry, Peter; Fry, Fiona (2002). A History of Scotland. Routledge. ISBN 978-1138174146.

- Morrill, John (1990). Oliver Cromwell and the English Revolution. Longman. ISBN 0582016754.

- Mullan, David (2000). Scottish Puritanism, 1590–1638. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-826997-8.

- Plant, David (2010). "The First Bishops War". Retrieved 27 January 2021.

- RPCNA. "Convictions;". Reformed Presbyterian Church of North America. Archived from the original on 1 September 2012. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Rees, John (2016). The Leveller Revolution. Verso. ISBN 978-1784783907.

- Robertson, Barry (2014). Royalists at War in Scotland and Ireland, 1638–1650. Ashgate. ISBN 978-1409457473.

- Royle, Trevor (2004). Civil War: The Wars of the Three Kingdoms 1638–1660 (2006 ed.). Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11564-1.

- SCMA. "Edinburgh Greyfriars Memorial". Covenanter.org. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Stephen, Jeffrey (2010). "Scottish Nationalism and Stuart Unionism". Journal of British Studies. 49 (1, Scottish Special). doi:10.1086/644534. S2CID 144730991.

- Stevenson, David (1973). Scottish Revolution, 1637–44: Triumph of the Covenanters. David & Charles. ISBN 0715363026.

- Wallace, Valerie (4 April 2017). "Radical Objects: Covenanter Gravestones as Political Protest". History Workshop. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- Webb, Stephen (1999). Lord Churchill's Coup: The Anglo-American Empire and the Glorious Revolution. Syracuse University Press.

- Wedgwood, CV (2001) [1958]. The King's War, 1641–1647. Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0141390727.

- Wilson, Peter H. (2009). Europe's Tragedy: A History of the Thirty Years War. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0-7139-9592-3.

- Wormald, Jenny (2018). Court, Kirk, and Community: Scotland, 1470–1625. Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 978-0748619399.

- Womersley, David (2015). James II (Penguin Monarchs): The Last Catholic King. Allen Lane. ISBN 978-0141977065.

Bibliography

- Buckroyd, J. Church and State in Scotland, 1660–1681. 1980

- Cowan, E. J. The Solemn League and Covenant, in Scotland and England, 1286–1815, ed. R. A. Mason, 1987.

- Cowan, I. B. The Covenanters: a Revision Article'' in The Scottish Historical Review, vol. 28, pp 43–54, 1949.

- Cowan, I. B. The Scottish Covenanters, 1660–1688, 1976

- Donaldson, G. Scotland from James V to James VII, 1965

- Fissel, M. C. The Bishops' Wars. Charles I's Campaigns against Scotland, 1638–1640, 1994

- Hewison, James King (1913a). The Covenanters. Vol. 1 (Revised and Corrected ed.). Glasgow: John Smith and son.

- Hewison, James King (1913b). The Covenanters. Vol. 2. Glasgow: John Smith and son.

- Hutchison, Matthew (1893). The Reformed Presbyterian Church in Scotland; its origin and history 1680–1876. Paisley : J. and R. Parlane.

- Johnston, John C (1887). Treasury of the Scottish covenant. Edinburgh: Andrew Elliot.

- Kiernan, V. G. A Banner with a Strange Device: the Later Covenanters, in History from Below, ed. K. Frantz, 1988.

- Lee, John (1860a). Lectures on the history of the Church of Scotland : from the Reformation to the Revolution Settlement. Vol. 1. Edinburgh: William Bleackwood.

- Lee, John (1860b). Lectures on the history of the Church of Scotland : from the Reformation to the Revolution Settlement. Vol. 2. Edinburgh: William Bleackwood.

- Love, Dane. Scottish Kirkyards, 1989 (Robert Hale Publishers, London).

- Mathieson, William Law (1902a). Politics and religion; a study in Scottish history from the reformation to the revolution. Vol. 1. Glasgow: J. Maclehose.

- Mathieson, William Law (1902b). Politics and religion; a study in Scottish history from the reformation to the revolution. Vol. 2. Glasgow: J. Maclehose.

- M'Crie, Thomas (1875). The story of the Scottish church : from the Reformation to the Disruption. London: Blackie & Son.

- Scot, William; Forbes, John (1846). An apologetical narration of the state and government of the Kirk of Scotland since the Reformation & Certaine records touching the estate of the kirk. Edinburgh: Printed for the Wodrow Society.

- Paterson, R C. A Land Afflicted, Scotland And The Covenanter Wars, 1638–1690, 1998

- Purves, Jock. Fair Sunshine. 1968

- Purves, Jock. Sweet Believing. Stirling, 1954

- Scott, Sir Walter. The Tale Of Old Mortality, 1816.

- Stevenson, D. The Scottish Revolution, 1637–1644, 1973.

- Terry, Charles Sanford (1905). The Pentland Rising & Rullion Green. Glasgow: J. MacLehose.

- Wodrow, Robert (1835a). Burns, Robert (ed.). The history of the sufferings of the church of Scotland... Vol. 1. Glasgow: Blackie, Fullarton & co.

- Wodrow, Robert (1830). Burns, Robert (ed.). The history of the sufferings of the church of Scotland... Vol. 2. Glasgow: Blackie Fullerton & Co.

- Wodrow, Robert (1829). Burns, Robert (ed.). The history of the sufferings of the church of Scotland... Vol. 3. Glasgow: Blackie Fullerton & Co.

- Wodrow, Robert (1835b). Burns, Robert (ed.). The history of the sufferings of the church of Scotland... Vol. 4. Glasgow: Blackie Fullerton & Co.

External links

- Who were the Covenanters? Scottish Covenanter Memorials Association

- The Reformed Presbyterian Church in North America

- The Reformed Presbyterian Church (Covenanted)

- Edinburgh's History: The Covenanters

- The Reformed Presbytery in North America

- British Civil Wars: The Scottish National Covenant

- British Civil Wars: The Covenanters

- The History of Protestantism – Volume Third – Book Twenty-fourth – Protestantism In Scotland

- Fenwick Kirk and the Covenanters

- The Covenants And The Covenanters, 1895, from Project Gutenberg

- The signing of the national covenant-1638/

The Covenanters. A Poetic Sketch by Letitia Elizabeth Landon in the Literary gazette, 1823.

The Covenanters. A Poetic Sketch by Letitia Elizabeth Landon in the Literary gazette, 1823.- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 339–340.