Divan of Algiers

Regency of Algiers دولة الجزائر (Arabic) | |

|---|---|

| 1516–1830 | |

Coat of arms of Algiers

(1516–1830) | |

| Motto: الجزائر المحروسة Algiers the well-guarded[2] | |

![Overall territorial extent of the Regency of Algiers in the late 17th to 19th centuries[3]](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e2/Alawids_and_Ottoman_regencies_in_17th-19th_centuries.png/300px-Alawids_and_Ottoman_regencies_in_17th-19th_centuries.png) Overall territorial extent of the Regency of Algiers in the late 17th to 19th centuries[3] | |

| Status | Autonomous eyalet (Client state) of the Ottoman Empire[4][5] |

| Capital | Algiers |

| Official languages | Arabic and Ottoman Turkish |

| Common languages | Algerian Arabic Berber Sabir (used in trade) |

| Religion | Official, and majority: Sunni Islam (Maliki and Hanafi) Minorities: Ibadi Islam Shia Islam Judaism Christianity |

| Demonym(s) | Algerian or Algerine |

| Government | 1516–1519: Sultanate 1519–1659: Viceroyalty 1659–1830: Stratocracy[6][7] (Political status) |

| Pasha | |

• 1516–1518 | Oruç Reis |

• 1710–1718 | Baba Ali Chaouch |

• 1818–1830 | Hussein Dey |

| Historical era | Early modern period |

| 1509 | |

| 1516 | |

| 1521–1791 | |

| 1541 | |

| 1550–1795 | |

| 1580–1640 | |

| 1627 | |

| 1659 | |

| 1681–1688 | |

| 1699–1702 | |

| 1775–1785 | |

| 1785–1816 | |

| 1830 | |

| Population | |

• 1830 | 3,000,000–5,000,000 |

| Currency | Major coins: mahboub (sultani) budju aspre Minor coins: saïme pataque-chique |

| Today part of | Algeria |

| History of Algeria |

|---|

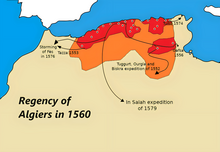

The Regency of Algiers[a] (Arabic: دولة الجزائر, romanized: Dawlat al-Jaza'ir) was an early modern tributary state of the Ottoman Empire on the Barbary Coast of North Africa from 1516 to 1830. Founded by the corsair brothers Oruç and Hayreddin Barbarossa, the regency was a formidable pirate base infamous for its corsairs, first ruled by Ottoman viceroys, and later a sovereign military republic[b] that plundered and waged maritime holy war against Christian powers.

The Algerian regency emerged in North Africa during the 16th-century Ottoman–Habsburg wars, a unique military oligarchy of janissaries and corsairs whose revenues and political power came from its maritime strength. When the war between the two empires ended in the early 17th century, merchant ships and goods belonging to France, England and the Netherlands were being captured and their crews and passengers enslaved. The Ottoman Sultan could not stop the attacks so the European powers dealt directly with the Regency, combining negotiations and strong sea operations, but by then the pirates had expanded across the Atlantic and the Barbary slave trade had reached its apex in Algiers. After the Janissary coup in 1659, elected local rulers emerged.

After wars with France, Maghrebi states and Spain in the 18th century over consolidation of territory, diplomatic relations with European states and Mediterranean trade, the American war of independence followed by extended U.S. shipping in the mediterranean, the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars allowed serious Algerian privateering bursts. Increased demand in tribute from Algiers caused the Barbary wars, in which American, British and Dutch navies engaged the Barbary corsairs at the beginning of the 19th century, decisively defeating Algiers for the first time. Internally, central authority weakened due to political intrigue and economic difficulties caused by failed harvests and the decline of privateering. This prompted violent tribal revolts, mainly led by maraboutic orders such as the Darqawis and Tijanis.

France took advantage of this situation to invade in 1830, leading to the French conquest of Algeria and eventually to French colonial rule until 1962.

History

Establishment (1516–1533)

Spanish expansion in the Maghreb

After the Emirate of Granada fell in 1492, the Spanish conquered cities in the Maghreb, establishing presidios, conquered ports transformed into garrisoned strongpoints, surrounded by formidable walls.[8] This allowed the Spaniards to control the waystations for caravans from western Sudan, Tripoli and Tunis in the east and Ceuta and Melilla in the west, via trade routes that passed through Béjaïa, Algiers, Oran and Tlemcen. Control over this trade and its two main commodities, gold and slaves, became essential to the Spanish treasury.[9]

The central Maghreb lost its previous role as a commercial middleman between Europe and Africa - especially in gold - leading to economic stagnation, a decline in trade, and a deterioration of craftsmanship in its two historical capitals, Béjaïa and Tlemcen. The country became politically fragmented, and its weak centralization was exacerbated by the Iberian trade monopoly, the activities of its merchant class, and the Spanish capacity to collect taxes.[10]

The Maghreb became vulnerable to incursions from the north shore of the Mediterranean. Within two decades, the Spanish Empire had captured multiple important cities and ports along the shores of the Maghreb. First came the conquest of Melilla in 1497,[11] then the Spanish took the Peñón de Vélez de la Gomera in 1508. Along Algerian shores, the city of Mers El Kébir fell in 1505, followed in 1509 by Oran - the most important sea port directly linked to Tlemcen, capital of the Zayyanid Kingdom.[12] After the capture of Béjaïa in Algeria, and the Spanish conquest of Tripoli in Libya in 1510, the Hafsids in Tunis decided they did not have the means to resist and chose to submit to Spanish sovereignty through humiliating agreements.[13]

Barbarossa brothers arrive

Ottoman privateer brothers Oruç and Hayreddin, both known to Europeans as Barbarossa, or "Red Beard" were corsair chiefs, skilful politicians as well as warriors feared by the Christian armies in the Mediterranean. In 1512, they were successfully operating off the coast of Hafsid Tunisia and famous for victories against Spanish naval vessels on the high sea and off the shores of Andalusia,[14] when scholars and notables of Bejaïa asked them to help dislodge the Spanish from Bejaïa. However they failed, due to that city's formidable fortifications. Oruç was wounded while trying to storm the city, and his arm had to be amputated.[15] He realized that his forces' position in the valley of La Goulette hampered their efforts against the Spaniards and moved them to Jijel, a center of trade between Africa and Italy, occupied since 1260 by the Genoese, where he received pleas for help from its inhabitants. Oruç conquered the city in 1514, establishing a base of operations there, and its inhabitants pledged allegiance to him as their prince,[16] as did the emir of Kuku, Ahmed Belkadi.[17] The emir urged Oruç to attack the Spaniards in Bejaïa again, so in 1514 Oruç besieged the city for nearly three months, ultimately to no avail. He made a third attempt in the spring of the following year with a larger force, but withdrew when his ammunition ran out and the Hafsid emir refused to supply any more. He did however succeed in capturing hundreds of Spanish prisoners.[18]

New masters of Algiers

The occupation of Bougie and the takeover of Oran by Pedro Navarro and Cardinal Francisco Jiménez de Cisneros alerted the Algerian population to the imminent threat they posed, and unable to resist the Spanish, they agreed to submit to them and recognize the Catholic king Ferdinand II of Aragon as their sovereign, pay a yearly tribute, release Christian prisoners, forsake piracy, and prevent the enemies of Spain from entering their harbor. A delegation of significant individuals escorted shaikh Salim al-Tumi of the Thaaliba to Spain, where he swore an oath of allegiance and presented gifts to Ferdinand. To ensure the fulfillment of the piracy requirements and to observe the residents of Algiers,[19] Pedro Navarro captured the island of Peñon, within artillery range of the city, and built a fort there, garrisoned with 200 men. The Algerians sought to break free of the Spanish and took advantage of the excitement over the death of King Ferdinand to seek help from Oruç and his men.[16]

A delegation from Algiers to Jijel in 1516 complained to Oruç of constant distress and danger. He abandoned his plans for another offensive against Bejaïa to help the citizens of Algiers, and set out at the head of 5,000 Kabyles and 1,500 Turks, followed by 800 arquebusiers, while Hayreddin led a naval fleet of 16 galliots. They rendezvoused in Algiers,[20] whose population celebrated their arrival and hailed them as heroes.[21] Hayreddin bombarded the Spanish Peñón of Algiers from sea, and Oruç took Cherchell, where he eliminated another Ottoman captain named Qara Hassan who had been cooperating with Andalusians.[16] Oruç did not possess the means to recover the Peñon of Algiers immediately, and since his presence often undermined al-Tumi's own authority, the latter eventually sought the help of the Spaniards to drive him out. In response, Oruc assassinated him [22] and proclaimed himself Sultan of Algiers, and raised his banners in green, yellow, and red above the forts of the city.[23][24][25] The Spaniards reacted by sending the governor of Oran, Diego de Vera, against Algiers in late September 1516. Oruç allowed De Vera's forces to land, then moved against them, taking advantage of their retreat and northern wind to drown and kill them, and also capture many prisoners, in a total defeat for the Spaniards, and a momentous victory for Oruç,[26] which expanded his influence further in the Algerian heartland.[27]

Campaign of Tlemcen and the Death of Oruç

Oruç decided to take action against the Spanish vassal Prince of Ténès Hamid bin Abid, and seized his city, vanquishing his army at the Battle of Oued Djer in June 1517. He killed the prince and expelled the Spaniards stationed there. Oruç then divided his kingdom into two parts: An eastern part based out of Dellys to be ruled by his brother Hayreddin, and a western part centered on the city of Algiers to be ruled by him personally.[28] While Oruç was in Ténès, a delegation from Tlemcen came to him to complain about the poor conditions in their country and the growing threat of a Spanish occupation of their city, exacerbated by squabbling between the Zayyanid princes over the throne.[16] Abu Ahmed III had seized the throne in Tlemcen by force after he expelled his nephew, Abu Zian III, and imprisoned him. Oruç elected to fulfill the wishes of the delegation, and appointed his brother Hayreddin as a ruler over the city of Algiers and its surroundings.[29]

Oruç marched towards Tlemcen, capturing the castle of the Banu Rashid along the way, and to protect his rear garrisoned it with a large force led by his brother Isaac. Oruç and his troops entered the city and released Abu Zayan from prison, restoring him to his throne, before progressing westward along the Moulouya to bring the Beni Amer and Beni Snassen tribes under his authority.[30] Abu Zayan began to conspire against Oruç, who arrested and executed him. Meanwhile, the deposed Abu Ahmed III fled to Oran to beg for help from his former enemies - the Spaniards - to retake his throne.[31] The Spaniards chose to answer his pleas, capturing the Banu Rashid castle and killing Isaac in late January 1519. Then they laid siege to Tlmecen. Oruç locked himself inside the Mechouar palace for several days to avoid the hostile populace, which eventually opened the gates for the Spanish.[30] Oruç attempted to flee Tlemcen, but the Spaniards pursued and killed him along with his Ottoman companions. His head was then sent to Spain, where it was paraded across its cities and those of Europe. His robes were also sent to the Church of St. Jerome in Cordoba, where they were kept as a trophy.[32]

Algiers joins the Ottoman Empire

Hayreddin was proclaimed Sultan of Algiers in late 1519.[33] Following a disastrous attempt by the Spanish Empire to take Algiers in 1519 led by Hugo of Moncada,[34] a rebellion attempt in Algiers and the reversal of his alliance with the Kingdom of Kuku after the death of its ruler, Ahmed Belkadi the elder, along with the deterioration of various forms of support on the internal level and growing Hafsid hostility in Tunis, Hayreddin became increasingly aware of the necessity of external Ottoman support to maintain his possessions around Algiers.[35] Thus, an assembly of Algerian notables and ulemas presented to Ottoman Sultan Selim I a proposal to attach Algiers to the Ottoman Empire.[36]

The delegation was tasked with making the strategic importance of Algiers in the Western Mediterranean understood to the Ottoman Sultan. Constantinople, which found the idea of integrating a territory so distant and so close to Spain perilous, but named Hayreddin Barbarossa beylerbey.[33] The important role of the regency fleet in the Ottoman maritime campaigns and its voluntary membership gave a particular character to the relations between Algiers and Constantinople. The regency was considered not a simple province but an imperial estate.[36] It also formed the spearhead of Ottoman power in the western Mediterranean.[37]

Hayreddin's reconquest of Algiers

After the defeat at Issers against the joint Kuku-Hafsid forces then the capture of Algiers in 1520, Sultan Belkadi and the Kabyles of Kuku began five to seven years of rule under over Algiers (1520–1525/1527).[38] Hayreddin retreated to Jijel in 1521 and he allied himself with the Kuku rivals, the Kabyles of Beni Abbas.[39] Hayreddin continued his progress in the east: taking Collo in 1521, Annaba and Constantine in 1523, then with the support of the Beni Abbès, he crossed their stronghold in the Babor Mountains, then the Soummam River. The Djurdjura was crossed without incident, but at Iflissen they had to face a detachment from Belkadi, which they defeated. Belkadi then withdrew to Tizi Naït Aicha (Thénia) to block the main roads to Algiers. Hayreddin detoured through the Mitidja plain.

Before the battle could take place, Belkadi was killed by one of his own soldiers, and the debacle caused by the assassination opened the way to Algiers, where the population, which had complained about Belkadi, opened the gates for Hayreddin in 1525 or 1527.[40]

But Algiers was still threatened by the Spaniards on the Peñon, from which they controlled the port. Hayreddin demanded the Spanish commander, Don Martin de Vargas, surrender with his garrison of two hundred soldiers. With this ultimatum rejected, he attacked and bombarded the Peñon and captured it on May 27, 1529.[41] The island was attached to the land and the harbor was enlarged to what would become a major port and headquarters of the Algerian corsair fleet.[42] The capture of the Peñon had a huge impact in Europe and Africa. The Ottomans were firmly established in Algiers.[41]

Morisco rescue missions

After he successfully had repelled Andrea Doria's Genoese navy landing on Cherchell in 1531,[43] Barbarossa sent ships to help Spanish Muslim Moriscos flee the Inquisition. Hayreddin's ships transported about 70,000 of them to the shores of Algiers.[44] Often, the number of ships was not enough to carry all the refugees. The pirates would then shuttle the refugees down the coast to a safer place, leaving them with guards while the pirates went back to rescue another load. In Algiers the Morisco refugees settled at the top of the city close to the Kasbah Palace, in the area known today as the "Tagarin", while others settled in other Algerian cities to the east and west, where they built, as Leo Africanus said: "2,000 houses, and among them were those who settled in Morocco and Tunisia. the Maghreb people learned much of their craft, imitated their luxury, and rejoiced in them".[44]

Hayreddin's successors (1534–1580)

Barbarossa was called in 1533 by the Sultan to exercise the function of Kapudan Pasha. He left Hasan Agha in command as his deputy and left for Constantinople in 1533.[45]

Two years later in 1535, Charles V of Spain conquered Tunis, defeating Hayreddin Barbarossa. In October 1541, he led another massive Imperial expedition, this time against Algiers, seeking to put an end to the Barbary pirates spreading terror in the western Mediterranean. It ended in total disaster for the Christian army.[46][47]

Successive expeditions set out to try to gain control of the city of Mostaganem. A first expedition set out in 1543, then a second in 1547,[48] in which Martín Alonso Fernández, Count of Alcaudete and his son Alonso de Córdoba were defeated due to poor planning, a shortage of ammunition, and a lack of experience and discipline among the Spanish troops.[49]

In 1544, Hasan Pasha, Hayreddin's son, became the first governor of the Regency of Algiers to be directly appointed by the Ottoman Sultan. According to Diego de Haëdo, he took the title of beylerbey as demanded by Hayreddin of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent.[50] After that, the conquest of Algeria sped up. In 1552, Salah Rais, with the help of Kabyle kingdoms of Kuku and Beni Abbas, conquered Touggourt, and established a foothold in the Sahara.[51] A year later, Salah Raïs expelled the Portuguese from the peñon of Valez and left a garrison there.[51]

Algerian-Sharifian conflicts shaped the western border of Algeria.[52] Saadian incursions in western Algeria resulted in the campaign of Tlemcen in 1551, where Hasan Pasha defeated the Moroccans, thus cementing Ottoman control in western Algeria.[48] This was followed by the Battle of Taza (1553) and the capture of Fez in 1554, in which Salih Raïs defeated the Moroccan army and conquered Morocco as far as Fez, and put Ali Abu Hassun in place as ruler and vassal to the Ottoman sultan.[53][54] This was followed by another campaign of Tlemcen in 1557, all of which the independent Kabylian kingdoms had significant involvement.[55] An Ottoman army was sent to Tuat against Mohammed al-Shaykh, the Saadi ruler of Morocco, to lift a blockade imposed by his troops, decisively defeating him.[56] In 1555, the Regency of Algiers managed to score a decisive victory against the Spanish Empire in Bougie and another in Mostaganem three years later, thus cementing Ottoman control in North Africa for good.[57] This was followed by a failed attempt to take Oran in 1563.[58]

After the failed Ottoman siege of Malta in 1565 and the Moriscos revolt in 1568, the beylerbey of Algiers, Uluç Ali, set off overland toward Tunis with 5300 Turks and 6000 Kabyle cavalry.[35] Uluç Ali defeated the Hafsid sultan at Béja, and conquered Tunis with few losses. He then led Algerian corsairs on the left wing of the Ottoman fleet in the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, and vanquished the Christian right wing led by Andrea Doria and his Maltese Knights, saving what remained of the defeated Ottoman navy.[59] Mulay Ahmad III was forced to take refuge in the Spanish presidio of La Goleta on the Bay of Tunis. The Christian forces were able to retake Tunis in 1573. However, the Ottomans under Uluç Ali conquered Tunis yet again in 1574.[60] The capture of Fez in 1576 resulted in Abd al-Malik being installed as an Ottoman vassal ruler over the Saadi Sultanate by Caïd Ramazan Pasha of Algiers.[61][62] In 1578 an army corps of the Regency was sent to Tuat once again against the Saadis and allied tribes from Tafilalt, sending "a written warning to the assailants".[56] During the 16th, 17th, and early 18th century, the Kabyle kingdom of Aït Abbas managed to maintain its independence, repelling several Ottoman attacks, notably in the First Battle of Kalaa of the Beni Abbès then in the Battle of Oued-el-Lhâm.[63]

In late 16th century, Algerian privateering reached its zenith in the mediterranean, as 28 ships near Málaga and 50 ships near Gibraltar strait were captured in a single season.[64] Raiding into Granada brought 4000 slaves to Algiers, while the waters from Valencia and Catalonia to Naples and Sicily were infested with Algerian pirate vessels.[65]

-

Shipwreck of Christian ships in the bay of Algiers, 1541

-

Barbary corsairs in the Battle of Lepanto (1571), by Laureys a Castro

-

Spanish Men-of-War Engaging Barbary Corsairs, by Cornelis Vroom (1590/1592–1661)

Golden Age of Algiers in 17th century

Algiers grew increasingly independent from Constantinople and engaged in widespread piracy in the 17th century "golden age of corsairs":[66] In the Mediterranean, the corsairs landed near Civitavecchia and took many prisoners in the Roman countryside. The goods taken by the Algerians were sold by merchants of Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Genoa and Livorno, who became the corsairs' brokers. Spain was powerless, Sicily and the small islands of Italy were incapable of opposing the raïs any longer.[67] The corsairs grew powerful at the Atlantic ocean once they adopted the use of round-bottomed vessels.[68] Exploring the routes of India and America, they disrupted the commerce of all enemy nations. In 1616, raïs Mourad the younger plundered the coasts of Iceland, and brought back 400 captives. In 1619 the corsairs ravaged Madeira. In 1631, they famously sacked Baltimore in Ireland, blocked the English Channel, and made catches in the North Sea.[69][70]

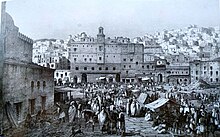

Algiers' port, navy, and population increased, reaching 100,000 to 125,000 people in the 17th century,[71] due to its pirate economy of forced exchange and paid protection for the safety of crews, cargo and ships at sea.[72][73] The Maghrebi population became wealthy from the sale of seized ships and cargo and from ransoms paid by for the release of prisoners captured on the high seas.[72] Their homes were built with "the most precious objects and delicacies from the European and Eastern worlds",[66] while over 25,000 slaves were held in Algiers.[74]

Ottoman suzerainty weakens

After the Battle of Lepanto in 1571, the Ottoman hold over Algiers weakened. The pasha represented Isbanbul, but did not in fact have full authority,[75] over time, the corsair captains known as "Raïs", and the janissaries of the "Odjak", acted only according to their interests.[76] In the early 17th century, European nations signed peace treaties with the Ottoman Empire, including Austria (1606) and the Netherlands (1612). Before that, France and Great Britain concluded so-called capitulations treaties with the Ottoman Empire in 1536 and 1579 respectively. These capitulations gave extraterritorial rights to foreigners living in the Ottoman Empire. They were originally intended to encourage trade. But Algiers disapproved of Constantinople's foreign policy, which it believed gave too many privileges to foreigners.[77]

Ottoman capitulations to France

The janissaries stationed in and paid by Algiers began ignoring the sultan and deciding war strategy at their military council, also known as the "dîwan", taking heed of neither the capidji (Imperial envoy) nor the alliances of Istanbul.[78] The Sublime Porte renewed a treaty in 1604 giving even more privileges to France, completely against Algerian interests. Clause 14 of the treaty authorized the French king to use force against Algiers if the treaty was broken. This prompted Khider Pasha of Algiers to attack a French trade center in eastern Algeria known as the Bastion of France. The pasha himself seized 6,000 sequins that Sultan Ahmed I had sent to compensate French merchants for losses caused by the raid on the Bastion, in clear defiance of the Ottoman treaty with France, for which the Sultan ordered Khider pasha hanged.[79] Still, the French could not rebuild the Bastion; King Henry IV envoy came to Algiers accompanied by a capidji from the Porte with a firman ordering the release of the French captives and the rebuilding of the Bastion, but the janissary Aghas revolted, and the dîwan refused to authorize reconstruction of the Bastion, and agreed to hand over the French captives only on condition that the Muslims detained in Marseilles were released,[80] indicating that relations with France were seen in a diverging way by Algiers and by Istanbul.[78]

Ali Bitchin Raïs

The raïs, who formerly responded to the sultan's slightest appeal, began to question his orders. They first demanded compensation for providing ships, and even to be paid in advance. In 1638, they felt betrayed by Istanbul; they were called by Sultan Murad IV to fight Venice, but a storm forced them to take shelter in the port at Valona, and the Venetians attacked them there and destroyed part of their fleet. The sultan refused to compensate the Algerians for their losses. Venice bribed the vizier and peace was made, to the great anger of the corsairs.[81][82]

Raïs Ali Bitchin, head of the tai'fa (community of Corsair captains) from 1630 to 1646, became the main leader in Algiers.[83] Admiral of all the galleys, head of the corporation of corsairs, he was immensely rich, with two palaces in Algiers, a mosque he had built, nearly 500 slaves, and a wife who was the daughter of the king of Kuku, Ali Bitchin wanted to pursue an independent policy, and refused Sultan Ibrahim IV's request to join the Cretan war.[84] The sultan wanted to arrest Ali Bitchin, but the population rose up and arrested the Pasha of Algiers. The dîwan tolerated Ali Bitchin's insubordination, but in return demanded that he pay the janissaries' wages. Ali Bitchin took refuge in Kabylia for nearly a year, then returned in force to Algiers and claimed the title of Pasha, demanding from Sultan Mehmed IV in 1649, 60,000 golden soltanis 16 galleys. The sultan appointed another pasha; when he arrived, Ali Bitchin suddenly died, perhaps poisoned.[83][84]

Foreign policy

In light of Algiers refusing to abide by the Capitulation treaties between the Sublime Porte and European states in the 17th century, Europe negotiated with Algiers through its admirals. Treaties were concluded about commerce, tribute payments and redemption of slaves.[77] Algerian relations with European powers were based on averting any coalition that could pose a serious threat. It played off adversaries who could have outmatched the Regency if they had united against it.[85] Very cleverly, the deys of Algiers tried to deal with each country separately, negotiating with the French to better attack the English or the Dutch, and vice versa,[67] giving a fine example of how useful this technique could be in the international relations of states.[c] Algiers was declaring war against every country with which it did not conclude a treaty. A European nation at war with Algiers almost inevitably could not compete with other shipping from nations at peace with the Regency.[86] In fact only ships from European countries that were at peace with Algiers could expand merchant shipping in the Mediterranean, called cabotage.[87] European vessels carried passports issued by their diplomatic mission in Algiers to protect them from Algerian cruisers and to resolve disputes over prizes.[77]

Kingdom of France

After more than 900 ships were taken and 8000 Frenchmen were reduced to slavery,[88] France decided to negotiate directly with Algiers beginning in 1617, but matters soon reached an impasse. Part of the trouble stemmed from the question of the return of two Algerian cannons the Dutch corsair Zymen Danseker had seized when he left the Algerian navy in 1607 and given to the Duke de Guise of Provence.[89] Two years later, a treaty was concluded in 1619,[90] then a second one in 1628,[91][92] upon which the Algerians undertook to:[93][94]

- Respect France's coast and vessels,

- Prohibit in their ports the sale of goods seized from French ships,

- Allow French traders to safely live in Algiers,

- Recognize and protect French concessions at the Bastion,

- Allow trade in leather and wax.

Sanson Napollon, head of the Bastion de France, was able to offer Marseille all the wheat it needed. In 1629 however, Marseille had fifteen corsairs of an Algerian ship massacred, and the rest taken prisoner to France.[95] In 1637, Ali Bitchin razed the French fortress and the dîwan decided that "never the said Bastion would recover, neither by request of the King of France, nor by command of the Grand Sultan, and that the first who would speak of it would lose his head".[96] But in 1640, a new treaty restored to France its establishments in Africa, and coral fishermen obtained assistance and security[96] in exchange for paying the Pasha a sum equivalent to nearly 17,000 pounds.[89][97]

In 1650, the raïs operated in the very waters of Marseilles, and ravaged Corsica, as France was engulfed in the Fronde. French Levant fleet and the Knights of Malta resumed their offensives against the Algerian fleet.[98] In 1658, Cardinal Mazarin gave the order to reconnoitre the Algerian coasts with a view to a permanent installation; he and First Minister of State Jean-Baptiste Colbert were advised on Bône, Jijel and Collo,[78] and sent large forces to occupy Collo in the spring of 1663, but the expedition ended in failure. In July 1664, King Louis XIV directed another military campaign against Jijel, which took nearly three months, but also ended in a defeat.[99] Despite a minor victory against Algerian vessels near Cherchell in 1655, France was forced to negotiate with Algiers and sign the May 7, 1666 agreement which stipulated the implementation of the 1628 treaty.[100][101] Louis XIV, who sought to have the French flag respected in the Mediterranean, sent several strong bombing campaigns against Algiers from 1682 to 1688 in what is known as the Franco-Algerian war.[67] After fierce resistance led by Dey Hussein Mezzomorto, a conclusive peace treaty was finally signed.[102]

Kingdom of England

In 1621, English admiral Robert Mansell took part in an expedition, in which he sent fireships (burning ships) against the pirate fleet moored in the bay of Algiers. This expedition was a failure and Mansell was recalled to England on May 24, 1621.[103] James I negotiated directly in Constantinople in 1622 with the Pasha of Algiers, who happened to be visiting there.[91][104] However, more than 3000 Englishmen were still enslaved in Algiers. A fleet under Admiral Blake, managed to sink several Tunisian ships, convincing Algiers to sign a peace treaty with Lord Protector Cromwell.[105] England introduced a series of anti-counterfeiting and mandatory 'Algerian passports' on its southbound merchant ships, guaranteeing each ship's authenticity in case it encountered Algerian pirate vessels.[106] Algiers faught a war with England where it lost several ships and 2200 sailors near Cape Spartel, and seven other ships were burned in Bougie, leading to a regime change in the Regency.[107] After the death of Charles II, and faced with dangerous French attacks in the 1680s, Algiers finally opted for a lasting peace with England that lasted more than 140 years.[108]

Dutch Republic

The Dutch recognized the impact of the Anglo-Algerian peace on their own shipping activities. Various reports of Armenian merchants arriving at The Hague, from the courts of Madrid or from Messina, all indicated that goods were being transferred from the Dutch to the British.[109] Thus, from 1661 to 1663, the Republic, under the command of Michiel de Ruyter, sent several squadrons of warships without success to settle the matter and force the Algerians to accept a treaty of permanent peace.[110]

From 1679 to 1686, the Republic was able to maintain an uneasy peace with Algiers thanks to the skills of the Dutch diplomat Thomas Hees, thus securing a significant share of peaceful trade with southern Europe,[111] in return for sending cannons, gunpowder and naval stores in form of tribute, which drew vivid condemnations from France and England.[112] Yet the peace did not last, and between 1714 and 1720, 40 ships were captured, and their seamen taken captive.[113]

After several military expeditions and lengthy negotiations the Dutch finally achieved the peace they had desired.[113] The new Dutch consul in Algiers, Ludwig Hameken, asked for a Mediterranean pass, and agreed to pay a yearly tribute for a whole century. When Britain went to war with Spain, the Dutch managed to stay ahead of their main rivals. But after the war, the British shipping industry in the Mediterranean flourished, and the Dutch couldn't keep up the competition.[114]

-

Battle of a French ship of the line and two galleys of the Barbary corsairs, by Théodore Gudin (1802–1880)

-

Combat between Portuguese vessels and Barbary pirates in 1685, by Peter Monamy (–1749)

-

HMS Mary Rose in battle with seven Algerian pirate ships on 28 December 1669, by Willem van de Velde the Younger

-

Action Between a Dutch Fleet and Barbary Pirates, by Lieve Verschuier

Maghrebi wars (1678–1756)

Algeria's relations with other Maghreb countries were mediocre for several historical reasons.[115] Algiers considered Tunisia a dependency because it had annexed it to the Ottoman Empire, which made the appointment of its pashas a prerogative of the Algerian beylerbeys.[116] Tunis, which had ambitions in the Constantine region inherited from the Hafsid era, rejected Algerian suzerainty. As for Morocco, which opposed the Ottomans with determination, viewed Algiers as a danger to its independence. Morocco also had ancient ambitions in western Algeria and Tlemcen in particular.[117] Both states also supported rebellions in Algiers, such as in 1692, when inhabitants of the capital and the neighboring tribes tried to get rid of Ottoman rule while Dey Hadj Chabane was campaigning in Morocco, setting fire to the port facilities and some of the ships anchored there.[118] On this basis, relations between Ottoman Algeria and its neighbors were troubled most of the time.[117]

Tunisian campaigns

Tunis adamantly refused subordination to Algeria. Beginning in 1590, the dîwan of Tunisian janissaries revolted against Algiers, and the country became a vassal of Constantinople itself.[117] A peace treaty concluded on May 17, 1628, following an Algerian victory was devoted to the delimitation of the borders between them.[119] In 1675, Murad II Bey died. This unleashed a twenty-year civil war between his sons.[120] Dey Chabane took this opportunity to lead victorious invasions of Tunis, such as the Battle of Kef, and the conquest of Tunis.[121] Fed up with this situation, Tunisians revolted and signed an alliance with the Sultan of Morocco, which soon culminated in the Maghrebi war.[115]

Murad III Bey of Tunis took the city of Constantine, but the regency of Algiers regained the upper hand in the Battle of Jouami' al-Ulama.[115] Ibrahim Cherif, the Agha of the Tunisian spahi cavalry, put an end to the Muradid regime and was named Dey by the militia and Pasha by the Ottoman sultan. However, he did not manage to put an end to the Algerian and Tripolitan incursions. Finally defeated near Kef by the Dey of Algiers on 8 July 1705, he was captured and taken to Algiers.[122] By this time, Hussein I ibn Ali Bey founded the Husainid dynasty of Tunis. After a failed revolt, Abu l-Hasan Ali I Pasha took refuge in Algiers, where he managed to gain the support of Dey Ibrahim Pasha.[123] Hassan Bey of Constantine dispatched a force of 7,000 men led by Danish slave Hark Olufs to invade Tunis in 1735 and install Ali Pasha as its bey,[124] who recognised he was a vassal of Algiers and paid an annual tribute to the dey.[124][125]

In another campaign directed against Tunis in 1756,[126] Ali I Pasha was deposed and brought to Algiers in chains, then strangled by supporters of his cousin and successor Muhammad I ar-Rashid on September 22. Algiers imposed a tribute on Tunis, which had to send oil to light the mosques of Algiers every year. Tunis became a tributary of Algiers and continued to pay an annual tribute and recognise Algerian suzerainty for more than 50 years.[127]

Moroccan campaigns

In 1678, Moulay Ismail mounted an expedition to Tlemcen.[128] He assembled his contingents in the Upper Moulouya, joined by the tribes of Orania, and advanced as far as the Chelif region to give battle there.[128] The Turks of Algiers brought in the artillery, which terrified the auxiliary tribes of the Moroccan sovereign, who then broke away from him. Moulay Ismail ended up negotiating with Dey Chabane and fixing the border on the Moulouya, which throughout the Saadian period, separated the two countries.[128] In 1691, Moulay Ismail launched a new offensive against Orania, and Dey Chabane defeated the attackers on the Moulouya and marched on Fez.[129] Moulay Ismail reportedly prostrated before the Dey in his tent, saying: "You are the knife and I the flesh that you can cut".[130][118] He agreed to pay tribute and sign the treaty of Oujda which confirmed the Moulouya river as the border.[131] In 1694, the sultan of Istanbul invited that of Morocco to cease his attacks against Algiers.[128]

In 1700, after coming to an agreement with the Tunisian Muradids that they were to simultaneously attack Constantine, the Moroccan sovereign launched a new expedition against Orania with an army composed mostly of Black Guards.[132] But Moulay Ismail's 60,000 men were beaten again at the Chelif river by Dey Hadj Mustapha.[133][134] Following these expeditions, the Dey of Algiers, Moustapha II, then wrote to Moulay Ismaïl about the attachment of the Algerians and their territory to the power of the regency of Algiers.[135]

As the Algerian assault on Spanish Oran was imminent, Moulay Ismail made one last attempt to capture Oran in 1707, but his army was almost entirely destroyed.[136][137] The Sharifians were still been able to preserve the independence of their country, but only by renouncing any project of expansion towards Orania.[138] In the following years Moulay Ismaïl led Saharan incursions towards Aïn Madhi and Laghouat without succeeding in settling them permanently.[134]

Dey Muhammad ben Othman Pasha (1766–1792)

Muhammad ben Othman Pasha assumed the position of dey in 1766 at the will of his predecessor, Dey Ali Bousaba, ruling over Algiers for a full quarter of a century until he died in 1791. He was a "rational, courageous, and determined man who adhered to working according to Islamic law, loved jihad, was austere even with regard to public treasury funds", according to Al-Zahar's narration.[139] Muhammad Othman succeeded with most of the problems he faced throughout his rule, especially with Spanish and Portuguese raids. He fortified the city of Algiers with a number of forts and towers, such as the Borj Sardinah, Borj Djedid, and Borj Ras Ammar. He repaired the Sayyida mosque next to Jenina Palace, which had been damaged by Spanish bombardment. He brought water to the city, and supplied it to all the castles, towers, fortresses, and mosques. He also built springs in the center of the city for people to drink from, and set up a special financial reserve for this water to take care of its streams and maintain them.[139]

The dey paid attention to strengthening the Algerian fleet and supplying it with men, weapons, and ships. A number of captains became famous during his reign, such as Raïs Hamidou, Raïs Haj Muhammad, Raïs Haj Suleiman and Raïs Ibn Yunus. According to Al-Zahar, Raïs Hajj Muhammad commanded about 24,000 men during his various maritime incursions.[140]

Pacification of the Regency

The population revolted in Blida, Al-Houdna and Isser, in some oases of the south and in Al-Nammasha in the Aurès.[141] The dey started his rule by leading campaigns against the tribes of Felissa in Kabylia, which were in constant rebellion. A first attempt in 1767 ended in failure and the tribes managed to reach the gates of Algiers itself. Nine years later however, the dey surrounded them in their mountains and made their leaders submit.[142] The eastern Salah Bey ben Mostefa of Constantine launched several expeditions to the south. In 1785, He marched through the Amour Range, then stormed Ain Beida and Aïn Madhi, and occupied all of Laghouat. He then received tribute from the Ibadi community of the south. In 1789, Salah bey occupied the city of Touggourt, and appointed Ben-Gana as "Sheikh of the Arabs" and imposed heavy tribute on the Berber Beni Djellab dynasty there.[143]

War with Denmark

Dey Muhammad Othman Pasha increased the annual royalties paid by the Netherlands, Venice, Sweden and Denmark. They accepted, except for Denmark, which refused and assigned Frederick Kaas to lead four ships of the line, two bomb galiots and two frigates, against the city of Algiers in 1770. The bombardment ended in failure.[144] Shortly after, Algerian pirates hijacked three Dano-Norwegian ships and their crews were sold as slaves.[145] Denmark submitted to the deys conditions and agreed to pay 2.5 million dollars in compensation for the damage to the city, and pledged to provide 44 cannons, 500 quintals of gunpowder, and 50 sails. It also agreed to ransom its captives and pay royalties every two years with various gifts to statesmen.[146]

War with Spain

Taking advantage of the War of the Spanish Succession, western bey Mustapha Bouchelaghem captured Oran and Mers-el Kebir in 1708.[147] But he eventually lost these cities to the Spanish after a successful campaign led by the Duke of Montemar in 1732.[148] In 1775, a Spanish expedition intended to reduce Mediterranean pirate activity was ordered by Irish admiral Alejandro O'Reilly. The assault was a spectacular failure and the campaign a humiliating blow to the Spanish military reorganisation.[149]

From August 1 to August 9, 1783, a Spanish squadron of 25 ships bombarded Algiers, but failed to overcome the defenses of the city. The Spanish squadron of four ships of the line and six frigates, did not inflict significant damage on the city and had to withdraw.[150] The commander of this fleet and that of 1784 was Spanish Admiral Antonio Barceló. A European league of the Spanish Empire, Kingdom of Portugal, Republic of Venice and Order of Saint John of Jerusalem, composed of 130 ships, bombarded Algiers on July 12, 1784. This failed, and the Spanish squadron fell back against the defense of the city.[151] Dey Mohamed ben-Osman asked for an indemnity of 1,000,000 pesos to conclude a peace in 1785. A period of negotiation (1785–87) followed to achieve a lasting peace between Algiers and Madrid.[152]

In 1791, the reconquest of Oran and Mers el-Kébir began. Oran, then under Spanish domination, was a concern for the Spanish court in the 18th century, which swung between two imperatives: preserving their presidency and maintaining a fragile peace with Algiers.[152] The death of Mohamed Ben-Osman and the election of Sidi Hassan, his khaznagy (vizier) as dey allowed negotiations to resume with Count Floridablanca: Spain undertook to "freely and voluntarily" restore the two cities. In exchange, it had the exclusive right to trade certain agricultural products in Oran and Mers-el-Kébir. The peace treaty signed, on February 12, 1792 Spanish soldiers evacuated Oran, and Mohammed el Kebir entered the city.[153]

Decline of Algiers (1800–1830)

Algerian Jewish merchants

The Jews of Algiers became an economic power, eliminating many European houses from the Mediterranean, which deeply worried the Marseillais, who sought to defend their threatened monopoly.[d] The French consuls resented the Jews almost violently and urged their King to pass ordinances that would prevent these favored Jews from trading in French ports. It was no use; the Jewish merchants had contacts, they dealt in prize goods from the corsairs as well as in more regular merchandise, and were essential to government because they were very skillful in mixing their personal affairs with the interests of the Algerian state.[154] They were at the origin of various Algerian disputes with Spain and especially with France.[154][155]

The French king was obliged to make good the losses of the French to avoid further difficulty. He established rules, port regulations, and tariff duties that made it practically impossible for Muslim merchants to trade in French harbors.[154] The Algerians could not actually transport their own cargoes of wool, hides, wheat, wax, or honey to the French market.[154] The Marseillais wanted, for example, to prohibit Algerian Jews from remaining more than three days in port, and appealed to the dey to prohibit Jews from trading in Marseilles. Muslim merchants, who had a cemetery in Marseilles, also wanted to build a mosque, but were refused. Moreover, the raïs, especially Christian converts to Islam, did not dare to land on Christian land, where they risked imprisonment and torture. Port regulations practically prevented them from trading with Europe in their own ships.[156]

Unable to have commercial vessels, or to transport their goods themselves to Europe, the Algerians used foreign intermediaries and fell back again on the corso to compensate them.[156]

Crisis of the 19th century

In the early 19th century, Algiers was struck with political turmoil and economic stress.[157] Failed wheat harvests caused misery, and resulted in public riots. Prominent Jewish merchant Naptali Busnac was held responsible for the shortages, since he was involved in the grain trade.[157] He was executed, and this was followed by repeated assassinations among the deys.[158]

Authorities burdened the population with heavy taxes and fines without taking into account their input or financial condition, under the pretext of constant "Holy war" with European states, and so they were ready to respond positively to every call for disobedience, to which the deys responded with brute force.[159] In 1792, incidents in Constantine led to the killing of popular Saleh Bey, a prominent administrative figure in the eastern Beylik. Algiers lost a political man and a seasoned military and administrative leader.[160] At the start of the 19th century, intrigues from the Moroccan court in Fez inspired the Zawiyas to stir up unrest and revolt.[161] Where Muhammad ibn Al-Ahrash, a marabout from Morocco and leader of the Darqawiyyah-Shadhili religious order, led the revolution in eastern Algeria, well aided by his Rahmaniyya allies.[162] The Darqawis in western Algeria joined the revolt and besieged Tlemcen, and the Tijanis also joined the revolt in the south. But the revolt was defeated by the bey Osman, who in turn was killed by Dey Hadj Ali.[163] In the meantime, Morocco would definitively take possession over Oujda in 1808,[164] and Tunisia would free itself from Algerian suzerainty following the wars of 1807 and 1813.[165]

Destructive earthquakes, and the occurrence of epidemics and drought in 1814, led to the death of thousands, causing in turn a severe reduction of the population and decline in trade.[158]

Barbary Wars

During the early 19th century, Algiers again resorted to widespread piracy against shipping from Europe and the United States of America, mainly due to internal fiscal difficulties, and taking advantage of the Napoleonic Wars.[166] Being the most notorious Barbary state,[167][168] Algiers declared war on the U.S which agreed to buy peace for $10 million including ransoms and annual tribute over 12 years.[166] Another treaty with Portugal brought $690.337 for ransome and $500.000 in tribute.[169] But Algiers was defeated in the Second Barbary War. Also, a new European order that arose from the French revolutionary wars and the Congress of Vienna no longer tolerated Algerian piracy, deeming it as "barbarous relic of a previous age".[170] This culminated in August 1816 when Lord Exmouth executed a naval bombardment of Algiers, resulting in a victory for the British and Dutch navies since it resulted in the weakening of the Algerian navy, and the liberation of 2000 Christian slaves.[171] Following this defeat, dey Omar Agha was killed, and his successor, dey Ali Khodja, suppressed turbulent elements of the Odjak with the help of Koulouglis and Zwawa troops, in an effort to stabilize the state.[170]

French invasion

During the Napoleonic Wars, the Regency of Algiers greatly benefited from trade in the Mediterranean, and the massive imports of food by France, largely bought on credit. In 1827, Hussein Dey, Algeria's ruler, demanded that the restored Kingdom of France pay a 31-year-old debt contracted in 1799 for supplies to feed the soldiers of the Napoleonic campaign in Egypt.[172]

French consul Pierre Deval didn't give answers satisfactory to the dey, and in an outburst of anger, Hussein Dey hit him with his fan. King Charles X used this as an excuse to break diplomatic relations and to start a full-scale invasion of Algeria on 14 June 1830. Algiers capitulated to the French on 5 July 1830 and Hussein Dey went into exile in Naples.[73] Charles X was overthrown a few weeks later by the July Revolution[172] and replaced by King Louis Philippe I.

Political status

After 1516, Algiers became the center of Ottoman rule in northwest Africa.[173] It was also a center of piracy for Muslims who attacked the ships of Christian countries; the island of Malta served Christian pirates in the same way.[173] The Regency was the headquarters of the Algerian janissary force, probably the greatest in the empire outside of Istanbul. With these powerful forces, Algiers quickly became a bastion of the Islamic world as the West competed with the Ottoman Empire for control of the western Mediterranean.[174] Fray Diego de Haedo, a Spanish Benedictine from Sicily, wrote between 1577 and 1581: "Aruj effectively began the great power of Algiers and the Barbary".[175]

State of Algiers established in 1516

Oruç's government

Oruç Barbarossa tried to build a powerful Muslim state in the center of the Maghreb at the expense of its principalities.[175] He sought the support of religious authorities, in particular of maraboutic and Sufi orders.[176] Exploiting the popularity of the marabouts for the benefit of his policy, he conveyed to them the idea of the form of government he was considering, called the "Odjak of Algiers".[27] Everything depended on a sort of a military republic, analogous to that of the island of Rhodes occupied by the Christian Knights Hospitaller.[177]

This constitution and the new power of Oruç, with religious sanction and the support of the scimitars of Turks and Christian renegades, allowed him a power freely accepted by the military, making his authority was absolute,[177] accepted without resistance by the population. Power was in the hands of the soldiers of the Odjak, and native Algerians and Kouloughlis were excluded from high government positions,[27] although they still held power over legal and police powers within Algiers as muftis, qadis, and mayors.[178]

Hayreddin's consolidation

Khair ad-Din Barbarossa inherited his brother's position without opposition. To contain the revolts of his opponents and fight the Spanish Empire, he pledged allegiance to the Sublime Porte, and had himself recognized as sovereign by the Sultan with the title of beylerbey.[31] The new pasha of Algiers in fact designed the strategy for the existence of the Algerian state. To govern the country, discuss and manage state affairs, he relied on a Council, the diwân, of carefully-chosen members.[179] Eventually, the members of the diwân were elected and for the most part came from the corps of Janissaries, as in Constantinople.[180] They became, even if they reflected the Ottoman ruling class, "the Algerians" of the state.[181][158] Barbarossa thus established the military basis of the regency,[182] formalising corsair activities into an institution through a well organized system of recruitment, financing and operations governing the infamous tai'fa of raïs, which would become a model for other Barbary corsairs in Tunis, Tripoli and the Republic of Salé.[183]

Ottoman Viceroyalty of Algiers (1519–1659)

Corsair kings: Beylerbeylik period (1519–1587)

In the first few decades, Algiers completely aligned with the Ottoman Empire, since the full authority of the country and the management of its affairs were in the hands of the beylerbey or governor-general. The beylerbeys were chosen from the corsair captains of Algiers, most of whom were companions of Khair ad-Din Barbarossa himself. The Ottoman Sultan appointed them over whomever the corsairs suggested as viceroys.[184] Often, one remained in power for several years. A number of them were also transferred to Constantinople to assume the position of Kapudan Pasha because of their experience in commanding naval fleets, such as Hayreddin Barbarossa, his son Hassan Pasha, and Uluj Ali Pasha.[42]

However, the beylerbeys were autonomous despite acknowledging the suzerainty of the Ottoman sultan; Spanish Benedictine and historian Diego de Haëdo called them "Kings of Algiers",[184] mainly because the "timar" system was not applied in Algiers, and the beylerbeys would instead send an annual tribute to Istanbul after meeting the expenses of state.[4][181] The sultan expected obedience in matters of foreign policy and to be provided with ships for his fleets when they were demanded. Otherwise the ruler was given a free hand to govern as he saw fit.[185] Eventually, the Algerian privateering aroused diverging internal and external interests of Algiers and Istanbul, with the latter unable to control it.[186]

Triennial mandate: Pashalik period (1587–1659)

Fearful of the growing independence of the rulers of Algiers, the Ottoman Empire abolished the beylerbeylik system in 1587, and established in its place the pashalik system,[187] as it divided the Maghreb countries under its dominion into three separate regencies: Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli.[188] This period lasted nearly 72 years, and was known for political instability, as power formally rested in the hands of governors sent from Istanbul and replaced every three years. However, the corsair captains were virtually outside their control, and the Janissaries' loyalty was limited by their ability to collect taxes and pay their salaries.[174] Yet it was also considered the "Golden Age of Algiers" due to its massive corsair fleet,[189][70] and the riches that filled the coffers of the regency thanks to intensified privateering.[66][187]

Aversion to the Sublime Porte increased in Algiers, mainly because Khider pasha and the Odjak strongly opposed the Ottoman capitulations.[190] Much like the corsairs, the Odjak grew stronger and expanded its influence very autonomously.[4][181] Already in 1596, Khider Pasha tried to get rid of the Odjak. A revolt sparked in the city of Algiers, and spread to neighboring towns, but the attempt failed.[191][192]

The latter pashas of Algiers were constantly lost between the demands of the corsairs and the Odjak, as both could refuse orders from the sultan or even send back appointed pashas.[186] Thus, the Pashas worked to multiply their treasures as quickly as possible while waiting for the end of their three-year term in office. As long as this was the main goal of the pashas, governance became a secondary issue, and little by little actual rule was transferred to the Janissary diwan. The pashas in Algiers, however, lost all influence and respect.[193]

Sovereign Military Republic of Algiers (1659–1830)

Janissary revolution: Agha regime in 1659

A massive revolution ignited when Ibrahim Pasha took a deduction from money that the Sultan had sent to the corsairs to compensate them for their losses in the Cretan War.[75] He was arrested and imprisoned.[194] Taking advantage of this incident, the commander-in-chief of the Janissaries stationed in Algiers, Khalil Agha, took power,[195][100] accusing the pashas sent by the Sublime Porte of being mostly corrupt and claiming that their governing hindered the regency's affairs with European countries.[54] The Janissaries effectively eliminated the authority of the pasha,[196] whose position became purely ceremonial. They agreed to assign executive authority to Khalil Agha, who inaugurated his rule by building the iconic "Djamaa el Djadid" mosque,[197] provided that the period of his rule did not exceed two months, then they put the legislative power in the hands of the Diwan Council. The Janissaries forced the Sultan to accept their new government under duress, but the Sultan stipulated that the Diwan pay the salaries of the Turkish soldiers. Thus began the era of the Aghas,[100] and the pashalik became a military republic.[198][199][200]

Military chiefs elective: Deylik period (1671–1830)

The government of the regency underwent another change in 1671 when the destruction of seven Algerian ships by a British squadron commanded by Sir Edward Spragge[201] occasioned a rebellion of the Corsairs and the assassination of Agha Ali (1664–71), the last of four janissary chiefs who had ruled the country since 1659, all of whom were killed.[45]

Ali Agha's death caught the leaders of the Regency unawares. The Odjak in rebellion tried to pursue the experiment of sovereign Aghas, but the designated candidates recused themselves one after the other. Under these conditions, the Odjak, with the agreement of the Ta'ifa of Raïs, resurrected the project of the late Ali Bitchin Raïs and resorted to an old expedient already in use in 1644–45, which consisted in entrusting the destiny of the Regency and the charge of the payroll to a raïs reputed to be solvent, an old Dutch renegade, "Hadj Mohammed Trik".[202][203] They gave him the titles of Dey (maternal uncle) and Doulateli (head of state) and Hakem (military ruler).[204] Thus, after 1671, the deys became the main leaders of the country.[202][205] In 1689, even though the dey came to be elected by the Odjak again, the Agha ceased to be ex officio the ruler of Ottoman Algeria.[45]

The pashas skilfully tried to regain some of their lost authority, and intrigued in the shadows, stirred up conflicts and fomented sedition to overthrow the unpopular deys.[195] From 1710 on, the deys assumed the title of Pasha, at the initiative of Dey Baba Ali Chaouch (1710–1718) and no longer accepted a representative of the sultan at their side, thus confirming their independence from the Sublime Porte.[206]

The deys also imposed their authority on the raïs and the Janissaries.[45] The former did not approve of the provisions which restricted privateering, their main source of income, as they remained attached to the external prestige of the Regency, the latter did not tolerate military defeat or delays in the payment. But the deys ended up triumphing over their revolts.[207] The raïs' lost the importance they had had in the 17th century; European reactions, new treaties guaranteeing the safety of navigation and a slowdown in shipbuilding considerably reduced its activity. The raïs were very unhappy with this situation, but they no longer had the strength to oppose the government. Their revolt in 1729 failed. They had risen up against Dey Mohamed ben Hassan, whom they accused of favoring the Janissaries to their detriment, and killed.[208] The new dey, Kurd Abdi (1724–1732), quickly restored order and severely punished the conspirators.[209] The Koulouglis of Tlmecen rebelled against Dey Ibrahim kuçuk, expelled the Turkish garrison from the city and tried to connect with the Koulouglis in Algiers. But the Dey, aware of the attempt, put an end to it.[210]

Administration

The organizations upon which the administrative apparatus of Ottoman Algeria relied were a mixture of borrowed Ottoman systems and local traditions inherited from previous stages of Islamic rule in the Maghreb, especially from the Almohad Caliphate, which were adopted by the courts of the Marinids, Zayyanids, and Hafsids. This was maintained through the regular recruitment of military elements from Ottoman lands in exchange for sending tribute to the Porte.[211]

Algerian stratocratic government

The Regency was described by some contemporary observers as a "republic".[e] According to priest and historian Pierre Dan (1580 –1649): "The state has only the name of a kingdom since, in effect, they have made it into a republic."[212] Algiers showed characteristics of a more "horizontal" and "egalitarian" structure than the European powers, which steadily succumbed to the absolutism of the monarchs.[212] It was unique among Muslim countries, and unusual even compared to 18th-century Europe, in having elected rulers through limited democracy. Jean-Jacques Rousseau was impressed by this.[213] Algiers was not a modern political democracy based on majority rule, alternation of power, and competition between political parties. Instead, politics was based on the principle of consensus (ijma), legitimized by Islam and by jihad.[213]

Dey of Algiers

The dey was in charge of the enforcement of civil and military laws, ensuring internal security, generating necessary revenues, organizing and providing regular pay for the troops and assuring correspondences with the tribes.[214] In principle, any member of the Janissary Odjak or the corsair captains could aspire to become Dey of Algiers through a system of "democracy by seniority."[212] Elections were accomplished through absolute equalty and unanimous vote among the armed forces.[215] Ottoman Algerian dignitary Hamdan Khodja indicates:[216]

Among the members of the government two of them are called, one "wakil-el-kharge", and the other "khaznagy". It is from these dignitaries that the dey is chosen; sovereignty in Algiers is not hereditary: personal merit is not transmitted to children. In a way we could say that they adopted the principles of a republic, of which the dey is only the president.

The election was required to have a confirmation from the Ottoman sultan who inevitably sent a firman of investiture, a red kaftan of honor, a saber of state and the attribution of the rank of Pasha of three Horsetails in the Ottoman army.[217] However, the dey was elected for life and could only be replaced after his death. Opponents could thus only gain power by overthrowing the current leader, leading to violence and instability. This volatility led many early 18th-century European observers to point to Algiers as an example of the inherent dangers of democracy.[213]

Dey's cabinet

The Dey appointed (except the Agha) and relied on 5 ministers to govern Algiers. These were the following:[45]

- Khaznaji : Prime minister in charge of finances and the public treasury. Transcription of the title make use of the appellations "vizier of the dey of Algiers", or "principal secretary of state".

- Agha of the Arabs : Commander-in-chief of the Odjak and minister of internal affairs, he was also responsible for governing Dar as-Soltan region of Algiers.

- Wakil al-Kharaj : Minister of navy and foreign affairs, he was the "Kapudan rais" or head of the Tai'fa of rais. He was also responsible for matters relating to weapons, ammunition and fortifications.

- Khodjat al-Khil : Responsible for the dey's connections with the tribes, managing fiscal responsibilities and collecting taxes, as he was usually at the head of expeditions to the tribes of the interior. Had also the ceremonial role of "secretary of horses" and was assisted by a "Khaznadar".[218]

- Bait al-Maldji : He was responsible for the State Domain (Makhzen) — and as such, for the rights devolved to the Treasury such as vacant inheritances, registration and confiscations.[218]

The dey also nominated muftis as the highest echelon of Algerian justice, based on their honesty and learning.[219]

Diwan council

The Diwan of Algiers was established in the 16th century by Hayreddin Barbarossa and seated first in the Jenina Palace then in the Casbah citadel. This assembly, initially led by a Janissary Agha, soon evolved from a means to administer the Odjak of Algiers to a primary institution of the country's administration.[220] Beginning around 1628, the Diwan expanded into two subdivisions:

- "The private (Janissary) Diwan" (diwan khass); Where any new recruit could rise up through the ranks at the rate of one every three years. Over time, he would serve among 60 Janissary bulukbasis (senior officers) with a vote on all that relates to high external and internal policy of the regency.[212] The commander-in-chief or "Agha of Two Moons" would be elected for a two months period as president of the Diwan. He also governed the regency during the Aghas period (1659–1671) with the title of "Hakem".[75]

- "The public, or Grand Divan" (diwan âm); Composed of Hanafi scholars and preachers, the Raïs, and native notables. It numbered between 800 and 1500 people.[221] In the 18th century, the Grand Diwan remained a large council of senior officials, notables, ulamas and senior officers of the Janissary militia, with a total of nearly 700 members. At the beginning of their mandate, the Deys consulted the divan on all important questions and decrees were deliberated. This council met in principle once a week, but this depended on the Dey, who, by the 19th century, could ignore the diwan whenever he felt powerful enough to govern alone.[222][220]

Territorial management

By the end of the 16th century, Algiers reached its frontiers which it secured until 1830.[115] The Regency was composed of various beyliks (provinces) under the authority of beys (vassals):[223]

- The Beylik of Constantine in the east, with its capital in Constantine

- The Beylik of Titteri in the centre, with its capital being Médéa

- The Beylik of the West, with its capital being Mascara and then Mazouna and then Oran

The administration of the western beylik was established in 1563. The capital was moved to Mazouna in 1710, then to Oran in 1791. The emirate of the southern beylik was established in 1548, with the capital in Médéa; it was called the Beylik of Tetri. The center of the eastern beylik was the city of Constantine. The central beylik included the city of Algiers with some nearby ports. These beyliks were institutionally divergent and enjoyed significant autonomy.[224]

Ottoman administration of Algeria relied on makhzen tribes.[196] Under the Beylik system, the Beys divided their Beyliks into chiefdoms. Each province was divided into outan, or counties, governed by caïds (commanders) under the authority of the Bey to maintain order and collect taxes from tributary regions.[225] Thus the Beys were empowered to run a small administrative system and manage their Beyliks with the help of their commanders and governors among the Makhzen tribes. In return, these tribes enjoyed special privileges including exemptions from paying taxes.[226] The Bey of Constantine relied on the strength of the local tribes, and at the forefront of those tribes were the Beni Abbas in Medjana and the Arab tribes in Zab region and Hodna, and the chiefs of these tribes were called "the Sheikh of the Arabs".[225] This system allowed the state of Algiers to expand its authority over the north of Algeria for three centuries. Despite this, certain regions only loosely acknowledged the authority of Algiers, leading to numerous revolts, confederations, tribal fiefs, and sultanates that contested the regency's control.[227]

-

Admiralty of Algiers in 1880, seat of Captain Raïs, harbor master and Wakil al-kharge (minister of the navy)

-

Palace of Mustafa Khodjet al-Khil (secretary of horses)

-

Inside Ahmed bey Palace, last governor of the eastern Beylik

-

Headquarter of the Janissaries by Henri Klein (1910)

Economy

Mandatory royalties and gifts

Algiers imposed royalties on its European trading partners in exchange for freedom of navigation in the western Mediterranean, and gave the merchants of those countries special privileges, including much lower customs duties. This prevented the character of banditry, piracy, or assault on the freedom of global trade from the part of the Algerian navy.[228] These royalties differed according to the relationship between those countries and Algiers, and the conditions prevailing in that period had an impact on determining the amounts of these royalties.These are shown in the following table:[229]

| Country | Year | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Spanish Empire | 1785 –1807 | After signing the armistice of 1785 and withdrawing from Oran, it was obliged to pay 18,000 francs. It contributed 48,000 dollars in 1807. |

| Grand Duchy of Tuscany | 1823 | Before 1823, it was obligated to pay the value of 25,000 doubles (Tuscan lira) or 250,000 francs. |

| Kingdom of Portugal | 1822 | It was obligated to pay the value of 20,000 francs. |

| Kingdom of Sardinia | 1746 - 1822 | Following the treaty of 1746, it was forced to pay 216,000 francs up by 1822. |

| Kingdom of France | 1790 - 1816 | Before the year 1790, it paid 37,000 pounds, and after 1790, it pledged to pay 27,000 piasters, or 108,000 Francs. And in 1816, it committed to pay the value of 200,000 francs. |

| United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland | 1807 | It pledged to pay 100,000 piasters, or 267,500 francs, in exchange for some privileges. |

| Kingdom of the Netherlands | 1807 - 1826 | After the treaty of 1826, it committed itself to paying 10,000 Algerian sequin, and in 1807, it paid the value of 40,000 piasters, or 160,000 francs. |

| Austrian Empire | 1807 | The value of the royalties paid in the year 1807 was estimated at 200,000 francs. |

| The United States of America | 1795 - 1822 | Paid in 1795 the value of 1,000,000 dollars, of which 21,600 dollars were in the form of equipment in exchange for special privileges. In the year 1822, it committed itself to paying 22,000 dollars. |

| Kingdom of Naples | 1816 - 1822 | Paid a royalty estimated at 24,000 francs. In 1822, a royalty of 12,000 francs was paid every two years. |

| Kingdom of Norway | 1822 | Paid a royalty of 12,000 francs every two years. |

| Kingdom of Denmark | 1822 | Paid a royalty of 180,000 francs every two years. |

| Kingdom of Sweden | 1822 | Paid a royalty of 120,000 francs every two years. |

| Republic of Venice | 1747 - 1763 | Since 1747, it has paid a royalty of 2,200 Gold coins annually. In 1763, the value of the royalties imposed on it became estimated at 50,000 riyals (Venetian lira). |

Royalties were imposed on Bremen, Hanover, and Prussia, in addition to the Papal States on some occasions.[229]

Taxation

Some of the taxes levied by the regency fell under Islamic law, including the cushr (tithe) on agricultural products, but some had elements of extortion.[230] Periodic tithes could only be collected on private land near the town where the crops were grown. Rather than tithes, the nomadic tribes of the mountains paid a fixed tax, called garama (compensation), based on a rough estimate of their wealth. In addition, the rural population paid a tax known as lazma (obligation) or ma'una (support), to pay for Muslim armies to defend the country from Christians. City dwellers had other taxes, including artisan guild dues and market taxes.[231] In addition, beys also collected gifts (dannush), every six months for the deys and their chief ministers. Every bey had to personally bring dannush every three years. In other years, his khalifa (deputy) took it to Algiers.[232]

The arrival of a bey or khalifa in Algiers with dannush was a notable event governed by a protocol setting out how to receive him and when his gifts were to be given to the dey, his ministers, officials and the poor. The honors that the bey received depended on the value of the gifts he brought. Al-Zahar reported that the chief of the western province was expected to pay more than 20,000 doro in cash, half that in jewelry, four horses, fifty black slaves, woollen tilimsan garments, Fez silk garments, and twenty quintals each of wax, honey, butter, and walnuts . Dannush from the Eastern Province was larger and included Tunisian products such as perfumes and clothing.[230]

Agriculture

Agricultural production benefited the regency even more than privateering at some point.[42] Fallowing and crop rotation were the most common techniques. Agricultural products were varied: wheat, corn, cotton, rice, tobacco, watermelon and vegetables were the most commonly grown.[233] Allowing for exports and local consumption, cereals and livestock products constituted much of the country's resources (oil, grain, wool, wax, leather).[234] On the outskirts of the towns, the very rich lands (fahs) provided various fruits, vegetables, vines, rice, cotton, blackberries used for breeding silkworms, Grapes and pomegranates were also cultivated. In the mountains, fruit trees, figs and olive trees grew.[235]

This wealth came first of all from the quality of the cultivated land, but also in the agricultural techniques, which used all the means of the time (ploughs, plows dragged by oxen, donkeys, mules, camels) and in a period of progress in agriculture, particularly in terms of irrigation and ingenious water supply supplying small collective dams. Mouloud Gaid attests: "Tlemcen, Mostaganem, Miliana, Médéa, Mila, Constantine, M'sila, Aïn El-Hamma, etc., were always sought after for their green site, their orchards and their succulent fruits."[236]

The majority of the western population south of the Tell Atlas and the people of the Sahara were pastoralists who lived from date cultivation and the products of sheep, goat and camel breeding. Livestock breeding was also the main activity of nomads and semi-nomads who sold their products each time they went north (butter, wool, skins, camel hair), while the population in the north and east settled in villages and practised agriculture. The state and urban notables owned lands near the main towns, cultivated by tenant farmers who were paid a fifth of the harvest, known as "khammas" system.[45] In the country, the large "melk" (properties), belonging to local feudal lords, represented the country's main wealth: vast areas of Algeria's best lands reserved for monoculture (wheat, barley, grazing). Due to the feudal nature of this regime, the distribution of usufruct was not always equitable and certain ousted members found themselves de facto excluded from their land by the tribe.[235]

Manufacturing and craftsmanship

Manufacturing was poorly developed and restricted to shipyards, which built frigates from 300 to 400 tons of oak wood from Béjaïa and Djidjel. The smaller ports of Ténès, Cherchell, Dellys, Béjaïa and Djidjel built shallops, brigs, galiots, tartanes and xebecs used for fishing and to transport goods between Algerian ports. Several workshops supported repairs and rope-making.[235] The quarries of Bougie, Skikda and Bab El-Oued extracted stone, raw material for buildings and fortifications. The Algerian navy ordered cannons of all sizes, manufactured at the Bab El-Oued foundries, for its warships. These cannons were also used for fort batteries and field artillery.[235]

Craftsmanship was rich and widespread across the country. Cities were centers of great craft and commercial activity.[234] Urban people were mostly artisans and merchants, notably in Nedroma, Tlemcen, Oran, Mostaganem, Kalaa, Dellys, Blida, Médéa, Collo, M'Sila, Mila and Constantine. The most common crafts were weaving, woodturning, dyeing, rope-making and tools.[237] In Algiers, a very large number of trades were practiced; the city was home to foundries, shipyards, workshops, shops, and stalls. Tlemcen had more than 500 looms. Even small towns where links to the rural world remained important had many craftsmen.[238]

Trade

Internal trade was extremely important due to the makhzen system, and large amounts of products needed in cities, such as wool, were brought in from the tribes of the interior, and traded between cities.[239] Foreign trade was mainly conducted by sea but also included overland exports to neighbouring countries such as Tunisia and Morocco.[234] Both internal and external overland trade transported goods mainly on the backs of animals, but also used carts. The roads were suitable for vehicles, and the many posts of the Odjak and the makhzen tribes provided security. In addition, caravanserais, locally known as fonduk, allowed travelers to rest.[239]

Although control over the Sahara was often loose, Algiers' economic ties with the Sahara were very important,[240] and Algiers and other Algerian cities were one of the main destinations of the trans-Saharan slave trade.[241]

Society

Turks numbering around 10,000 made up the ruling class of Algerian society, which included senior officials, politicians, administrators, and soldiers.[242] However, there were no harems in Algiers since the elected rulers were often politically challenged.[243] In addition, society included Kouloughlis,[244] indigenous Algerians, Blacks, urban arrivals from Andalusia and a Jewish minority.[245] Muslims, mostly of the Maliki school, represented 99% of the population;[234] they mostly engaged in farming and livestock breeding, with a minority engaged in craft and commercial activities. The bourgeoisie lived in the coastal cities and owned the best homes and land. Urban residents represented only 6% of the population but lived in cities equipped with public facilities such as springs, fountains, cafes, bathrooms, restaurants, hotels, and shops.

Algiers alone had 60 coffeehouses.[234] The city closed its gates at nightfall. Religious holidays were Islamic holidays and Friday was devoted to religion. Public business was carried out in Arabic and Osmanli.[246]

Social formations

In precolonial Maghreb, the tribe was a primary political structure and could itself be the central power or reigning dynasty in the makhzen system. Others were independent in a dissident territory (siba). This system persisted under the Regency. A complex link developed between tribes and the central state, with tribes adapting to central government pressure.[247][248]

Central authority was sometimes necessary for the consolidation of the tribe. These relations even seemed complementary.[248] Indeed, makhzen tribes derived their legitimacy from their relationship to the central power. Without it, they were reduced to relying on their own strength. The rayas (tax payers) and siba tribes seemed to oppose taxes, which reduced their surplus production, more than the central authority itself, and depended on market access organized by the authorities and makhzen tribes.[249] Even in dissent, tribes often organized themselves as another authority, which made the markets outside the territories dependent on the central powers managed by the marabouts or the maraboutic lineages. The latter, in the absence of the central authority, very often acted as guarantors of tribal order.[247]