Emily Davison

Emily Wilding Davison (11 October 1872 – 8 June 1913) was an English suffragette who fought for votes for women in Britain in the early twentieth century. A member of the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) and a militant fighter for her cause, she was arrested on nine occasions, went on hunger strike seven times and was force-fed on forty-nine occasions. She died after being hit by King George V's horse Anmer at the 1913 Derby when she walked onto the track during the race.

Davison grew up in a middle-class family, and studied at Royal Holloway College, London, and St Hugh's College, Oxford, before taking jobs as a teacher and governess. She joined the WSPU in November 1906 and became an officer of the organisation and a chief steward during marches. She soon became known in the organisation for her militant action; her tactics included breaking windows, throwing stones, setting fire to postboxes, planting bombs and, on three occasions, hiding overnight in the Palace of Westminster—including on the night of the 1911 census. Her funeral on 14 June 1913 was organised by the WSPU. A procession of 5,000 suffragettes and their supporters accompanied her coffin and 50,000 people lined the route through London; her coffin was then taken by train to the family plot in Morpeth, Northumberland.

Davison was a staunch feminist and passionate Christian, and considered that socialism was a moral and political force for good. Much of her life has been interpreted through the manner of her death. She gave no prior explanation for what she planned to do at the Derby and the uncertainty of her motives and intentions has affected how she has been judged by history. Several theories have been put forward, including accident, suicide or an attempt to pin a suffragette banner to the king's horse.

Biography

Early life and education

Emily Wilding Davison was born at Roxburgh House, Greenwich, in south-east London on 11 October 1872. Her parents were Charles Davison, a retired merchant, and Margaret née Caisley, both of Morpeth, Northumberland.[1] At the time of his marriage to Margaret in 1868, Charles was 45 and Margaret was 19.[2] Emily was the third of four children born to the couple; her younger sister died of diphtheria in 1880 at the age of six.[3][4][5] The marriage to Margaret was Charles's second; his first marriage produced nine children before the death of his wife in 1866.[1]

The family moved to Sawbridgeworth, Hertfordshire, while Davison was still a baby; until the age of 11 she was educated at home. When her parents moved the family back to London she went to a day school, then spent a year studying in Dunkirk, France.[6] When she was 13 she attended Kensington High School and later won a bursary to Royal Holloway College in 1891 to study literature. Her father died in early 1893 and she was forced to end her studies because her mother could not afford the fees of £20 a term.[7][a]

On leaving Holloway, Davison became a live-in governess, and continued studying in the evenings.[9] She saved enough money to enrol at St Hugh's College, Oxford, for one term to sit her finals;[b] she achieved first-class honours in English, but could not graduate because degrees from Oxford were closed to women.[11] She worked briefly at a church school in Edgbaston between 1895 and 1896, but found it difficult and moved to Seabury, a private school in Worthing, where she was more settled; she left the town in 1898 and became a private tutor and governess to a family in Northamptonshire.[11][12][13] In 1902 she began reading for a degree at the University of London; she graduated with third-class honours in 1908.[14][c]

Activism

Davison joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU) in November 1906.[16] Formed in 1903 by Emmeline Pankhurst, the WSPU brought together those who thought that militant, confrontational tactics were needed to achieve their ultimate goal of women's suffrage.[17][d] Davison joined in the WSPU's campaigning and became an officer of the organisation and a chief steward during marches.[19] In 1908 or 1909 she left her job teaching and dedicated herself full-time to the union.[1] She began taking increasingly confrontational actions, which prompted Sylvia Pankhurst—the daughter of Emmeline and a full-time member of the WSPU—to describe her as "one of the most daring and reckless of the militants".[20][21] In March 1909 she was arrested for the first time; she had been part of a deputation of 21 women who marched from Caxton Hall to see the prime minister, H. H. Asquith,[22] the march ended in a fracas with police and she was arrested for "assaulting the police in the execution of their duty". She was sentenced to a month in prison.[23][24] After her release she wrote to Votes for Women, the WSPU's newspaper, saying that "Through my humble work in this noblest of all causes I have come into a fullness of job and an interest in living which I never before experienced".[25]

In July 1909 Davison was arrested with fellow suffragettes Mary Leigh and Alice Paul for interrupting a public meeting from which women were barred, held by the Chancellor of the Exchequer, David Lloyd George; she was sentenced to two months for obstruction. She went on hunger strike and was released after five and a half days,[22][26] during which time she lost 21 pounds (9.5 kg); she stated that she "felt very weak" as a result.[27] She was arrested again in September the same year for throwing stones to break windows at a political meeting; the assembly, which was to protest at the 1909 budget, was only open to men. She was sent to Strangeways prison for two months. She again went on hunger strike and was released after two and a half days.[28] She subsequently wrote to The Manchester Guardian to justify her action of throwing stones as one "which was meant as a warning to the general public of the personal risk they run in future if they go to Cabinet Ministers' meetings anywhere". She went on to write that this was justified because of the "unconstitutional action of Cabinet Ministers in addressing 'public meetings' from which a large section of the public is excluded".[29][30]

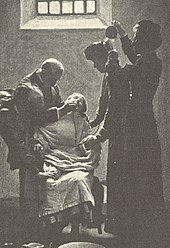

Davison was arrested again in early October 1909, while preparing to throw a stone at the cabinet minister Sir Walter Runciman; she acted in the mistaken belief the car in which he travelled contained Lloyd George. A suffragette colleague—Constance Lytton—threw hers first, before the police managed to intervene. Davison was charged with attempted assault, but released; Lytton was imprisoned for a month.[31] Davison used her court appearances to give speeches; excerpts and quotes from these were published in the newspapers.[32] Two weeks later she threw stones at Runciman at a political meeting in Radcliffe, Greater Manchester; she was arrested and sentenced to a week's hard labour. She again went on hunger strike, but the government had authorised the use of force-feeding on prisoners.[23][33] The historian Gay Gullickson describes the tactic as "extremely painful, psychologically harrowing, and raised the possibility of dying in jail from medical error or official misjudgment".[27] Davison said that the experience "will haunt me with its horror all my life, and is almost indescribable. ... The torture was barbaric".[34] Following the first episode of forced feeding, and to prevent a repeat of the experience, Davison barricaded herself in her cell using her bed and a stool and refused to allow the prison authorities to enter. They broke one of the window panes to the cell and turned a fire hose on her for 15 minutes, while attempting to force the door open. By the time the door was opened, the cell was six inches deep in water. She was taken to the prison hospital where she was warmed with hot water bottles. She was force-fed shortly afterwards and released after eight days.[35][36] Davison's treatment prompted the Labour Party MP Keir Hardie to ask a question in the House of Commons about the "assault committed on a woman prisoner in Strangeways";[37] Davison sued the prison authorities for the use of the hose and, in January 1910, she was awarded 40 shillings in damages.[38]

In April 1910 Davison decided to gain entry to the floor of the House of Commons to ask Asquith about the vote for women. She entered the Palace of Westminster with other members of the public and made her way into the heating system, where she hid overnight. On a trip from her hiding place to find water, she was arrested by a policeman, but not prosecuted.[39][40] The same month she became an employee of the WSPU and began to write for Votes for Women.[41][42][e]

A bipartisan group of MPs formed a Conciliation Committee in early 1910 and proposed a Conciliation Bill that would have brought the vote to a million women, so long as they owned property. While the bill was being discussed, the WSPU put in a temporary truce on activity. The bill failed that November when Asquith's Liberal government reneged on a promise to allow parliamentary time to debate the bill.[44] A WSPU delegation of around 300 women tried to present him with a petition, but were prevented from doing so by an aggressive police response; the suffragettes, who called the day Black Friday, complained of assault, much of which was sexual in nature.[45][46] Davison was not one of the 122 people arrested, but was incensed by the treatment of the delegation; the following day she broke several windows in the Crown Office in parliament. She was arrested and sentenced to a month in prison. She went on hunger strike again and was force-fed for eight days before being released.[47][f]

On the night of the 1911 census, 2 April, Davison hid in a cupboard in St Mary Undercroft, the chapel of the Palace of Westminster. She remained hidden overnight to avoid being entered onto the census; the attempt was part of a wider suffragette action to avoid being listed by the state. She was found by a cleaner, who reported her presence; Davison was arrested but not charged. The Clerk of Works at the House of Commons completed a census form to include Davison in the returns. She was included in the census twice, as her landlady also included her as being present at her lodgings.[49][50][g] Davison had continually written letters to the press to put forward the WSPU position in a non-violent manner—she had 12 published in The Manchester Guardian between 1909 and 1911—and she undertook a campaign between 1911 and 1913 during which she wrote nearly 200 letters to over 50 newspapers.[51][52] Several of her letters were published, including about 26 in The Sunday Times between September 1910 and 1912.[53]

Davison developed the new tactic of setting fire to postboxes in December 1911. She was arrested for arson on the postbox outside parliament and admitted to setting fire to two others. Sentenced to six months in Holloway Prison, she did not go on hunger strike at first, but the authorities required that she be force-fed between 29 February and 7 March 1912 because they considered her health and appetite to be in decline. In June she and other suffragette inmates barricaded themselves in their cells and went on hunger strike; the authorities broke down the cell doors and force-fed the strikers.[54] Following the force-feeding, Davison decided on what she described as a "desperate protest ... made to put a stop to the hideous torture, which was now our lot" and jumped from one of the interior balconies of the prison.[55] She later wrote:

... as soon as I got out I climbed on to the railing and threw myself out to the wire-netting, a distance of between 20 and 30 feet. The idea in my mind was "one big tragedy may save many others". I realised that my best means of carrying out my purpose was the iron staircase. When a good moment came, quite deliberately I walked upstairs and threw myself from the top, as I meant, on to the iron staircase. If I had been successful I should undoubtedly have been killed, as it was a clear drop of 30 to 40 feet. But I caught on the edge of the netting. I then threw myself forward on my head with all my might.[55]

She cracked two vertebrae and badly injured her head. Shortly afterwards, and despite her injuries, she was again force-fed before being released ten days early.[23][56] She wrote to The Pall Mall Gazette to explain why she "attempted to commit suicide":

I did it deliberately and with all my power, because I felt that by nothing but the sacrifice of human life would the nation be brought to realise the horrible torture our women face! If I had succeeded I am sure that forcible feeding could not in all conscience have been resorted to again.[57]

As a result of her action Davison suffered discomfort for the rest of her life.[21] Her arson of postboxes was not authorised by the WSPU leadership and this, together with her other actions, led to her falling out of favour with the organisation; Sylvia Pankhurst later wrote that the WSPU leadership wanted "to discourage ... [Davison] in such tendencies ... She was condemned and ostracized as a self-willed person who persisted in acting upon her own initiative without waiting for official instructions."[58] A statement Davison wrote on her release from prison for The Suffragette—the second official newspaper of the WSPU—was published by the union after her death.[1][59]

In November 1912 Davison was arrested for a final time, for attacking a Baptist minister with a horsewhip or dogwhip, while on a stationary train in Aberdeen railway station; she had mistaken the man for Lloyd George. She was sentenced to ten days' imprisonment and released early following a four-day hunger strike.[23][60] It was the seventh time she had been on hunger strike, and the forty-ninth time she had been force-fed.[61]

Fatal injury at the Derby

On 4 June 1913 Davison obtained two flags bearing the suffragette colours of purple, white and green from the WSPU offices; she then travelled by train to Epsom, Surrey, to attend the Derby.[62] She positioned herself in the infield at Tattenham Corner, the final bend before the home straight. At this point in the race, with some of the horses having passed her, she ducked under the guard rail and ran onto the course; she may have held in her hands one of the suffragette flags. She reached up to the reins of Anmer—King George V's horse, ridden by Herbert Jones—and was hit by the animal, which would have been travelling at around 35 miles (56 km) per hour,[63][64] four seconds after stepping onto the course.[65] Anmer fell in the collision and partly rolled over his jockey, who had his foot momentarily caught in the stirrup.[63][64] Davison was knocked to the ground unconscious; some reports say she was kicked in the head by Anmer, but the surgeon who operated on Davison stated that "I could find no trace of her having been kicked by a horse".[66] The event was captured by three newsreel cameras.[67][h]

Bystanders rushed onto the track and attempted to aid Davison and Jones until both were taken to the nearby Epsom Cottage Hospital. Davison was operated on two days later, but she never regained consciousness; while in hospital she received hate mail.[69][70][i] She died on 8 June, aged 40, from a fracture at the base of her skull.[73][74] Found in Davison's effects were the two suffragette flags, the return stub of her railway ticket to London, her race card, a ticket to a suffragette dance later that day and a diary with appointments for the following week.[75][76][j] The King and Queen Mary were present at the race and made enquiries about the health of both Jones and Davison. The King later recorded in his diary that it was "a most regrettable and scandalous proceeding"; in her journal the Queen described Davison as a "horrid woman".[78] Jones suffered a concussion and other injuries; he spent the evening of 4 June in London, before returning home the following day.[79] He could recall little of the event: "She seemed to clutch at my horse, and I felt it strike her."[80] He recovered sufficiently to race Anmer at Ascot Racecourse two weeks later.[76]

The inquest into Davison's death took place at Epsom on 10 June; Jones was not well enough to attend.[81] Davison's half-brother, Captain Henry Davison, gave evidence about his sister, saying that she was "a woman of very strong reasoning faculties, and passionately devoted to the women's movement".[82] The coroner decided that, in the absence of evidence to the contrary, Davison had not committed suicide.[83] The coroner also decided that, although she had waited until she could see the horses, "from the evidence it was clear that the woman did not make for His Majesty's horse in particular".[83] The verdict of the court was:

that Miss Emily Wilding Davison died of fracture of the base of the skull, caused by being accidentally knocked down by a horse through wilfully rushing on to the racecourse on Epsom Downs during the progress of the race for the Derby; death was due to misadventure.[82]

Davison's purpose in attending the Derby and walking onto the course is unclear. She did not discuss her plans with anyone or leave a note.[84][85] Several theories have been suggested, including that she intended to cross the track, believing that all horses had passed; that she wanted to pull down the King's horse; that she was trying to attach one of the WSPU flags to a horse; or that she intended to throw herself in front of one of the horses.[73] The historian Elizabeth Crawford considers that "subsequent explanations of ... [Davison's] action have created a tangle of fictions, false deductions, hearsay, conjecture, misrepresentation and theory".[86]

In 2013 a Channel 4 documentary used forensic examiners who digitised the original nitrate film from the three cameras present. The film was digitally cleaned and examined. Their examination suggests that Davison intended to throw a suffragette flag around the neck of a horse or attach it to the horse's bridle.[k] A flag was gathered from the course; this was put up for auction and, as at 2021, it hangs in the Houses of Parliament.[73] Michael Tanner, the horse-racing historian and author of a history of the 1913 Derby, doubts the authenticity of the item. Sotheby's, the auction house that sold it, describe it as a sash that was "reputed" to have been worn by Davison. The seller stated that her father, Richard Pittway Burton, was the Clerk of the Course at Epsom; Tanner's search of records shows Burton was listed as a dock labourer two weeks prior to the Derby. The official Clerk of the Course on the day of the Derby was Henry Mayson Dorling.[88] When the police listed Davison's possessions, they itemised the two flags provided by the WSPU, both folded up and pinned to the inside of her jacket. They measured 44.5 by 27 inches (113 × 69 cm); the sash displayed at the Houses of Parliament measures 82 by 12 inches (210 × 30 cm).[89]

Tanner considers that Davison's choice of the King's horse was "pure happenstance", as her position on the corner would have left her with a limited view.[90] Examination of the newsreels by the forensic team employed by the Channel 4 documentary determined that Davison was closer to the start of the bend than had been previously assumed, and would have had a better view of the oncoming horses.[65][73]

The contemporary news media were largely unsympathetic to Davison,[91] and many publications "questioned her sanity and characterised her actions as suicidal".[92] The Pall Mall Gazette said it had "pity for the dementia which led an unfortunate woman to seek a grotesque and meaningless kind of 'martyrdom' ",[93] while The Daily Express described Davison as "A well-known malignant suffragette, ... [who] has a long record of convictions for complicity in suffragette outrages."[94] The journalist for The Daily Telegraph observed that "Deep in the hearts of every onlooker was a feeling of fierce resentment with the miserable woman";[91] the unnamed writer in The Daily Mirror opined that "It was quite evident that her condition was serious; otherwise many of the crowd would have fulfilled their evident desire to lynch her."[95]

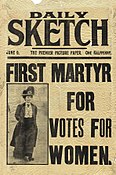

The WSPU were quick to describe her as a martyr, part of a campaign to identify her as such.[96][97] The Suffragette newspaper marked Davison's death by issuing a copy showing a female angel with raised arms standing in front of the guard rail of a racecourse.[98] The paper's editorial stated that "Davison has proved that there are in the twentieth-century people who are willing to lay down their lives for an ideal".[99] Religious phraseology was used in the issue to describe her act, including "Greater love hath no man than this, that he lay down his life for his friends", which Gullickson reports as being repeated several times in subsequent discussions of the events.[100] A year after the Derby, The Suffragette included "The Price of Liberty", an essay by Davison. In it, she had written "To lay down life for friends, that is glorious, selfless, inspiring! But to re-enact the tragedy of Calvary for generations yet unborn, that is the last consummate sacrifice of the Militant".[101]

Funeral

On 14 June 1913 Davison's body was transported from Epsom to London; her coffin was inscribed "Fight on. God will give the victory."[102] Five thousand women formed a procession, followed by hundreds of male supporters, that took the body between Victoria and Kings Cross stations; the procession stopped at St George's, Bloomsbury for a brief service[103] led by its vicar, Charles Baumgarten, and Claude Hinscliff, who were members of the Church League for Women's Suffrage.[104] The women marched in ranks wearing the suffragette colours of white and purple, which The Manchester Guardian described as having "something of the deliberate brilliance of a military funeral";[103] 50,000 people lined the route.[105] The event, which was organised by Grace Roe,[104] is described by June Purvis, Davison's biographer, as "the last of the great suffragette spectacles".[96] Emmeline Pankhurst planned to be part of the procession, but she was arrested on the morning, ostensibly to be returned to prison under the "Cat and Mouse" Act (1913).[82][103][l]

The coffin was taken by train to Newcastle upon Tyne with a suffragette guard of honour for the journey; crowds met the train at its scheduled stops. The coffin remained overnight at the city's central station before being taken to Morpeth. A procession of about a hundred suffragettes accompanied the coffin from the station to the St. Mary the Virgin church; it was watched by thousands. Only a few of the suffragettes entered the churchyard, as the service and interment were private.[103][107] Her gravestone bears the WSPU slogan "Deeds not words".[108]

Approach and analysis

Davison's death marked a culmination and a turning point of the militant suffragette campaign. The First World War broke out the following year and, on 10 August 1914, the government released all women hunger strikers and declared an amnesty. Emmeline Pankhurst suspended WSPU operations on 13 August.[110][111] Pankhurst subsequently assisted the government in the recruitment of women for war work.[112][113] In 1918 Parliament passed the Representation of the People Act 1918. Among the changes was the granting of the vote to women over the age of 30 who could pass property qualifications.[m] The legislation added 8.5 million women to the electoral roll; they constituted 43% of the electorate.[114][115] In 1928 the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act lowered the voting age for women to 21 to put them on equal terms with male voters.[116][117]

Crawford sees the events at the 1913 Derby as a lens "through which ... [Davison's] whole life has been interpreted",[11] and the uncertainty of her motives and intentions that day has affected how she has been judged by history.[97][118] Carolyn Collette, a literary critic who has studied Davison's writing, identifies the different motives ascribed to Davison, including "uncontrolled impulses" or a search for martyrdom for women's suffrage. Collette also sees a more current trend among historians "to accept what some of her close contemporaries believed: that Davison's actions that day were deliberate" and that she attempted to attach the suffragette colours to the King's horse.[118] Cicely Hale, a suffragette who worked at the WSPU and who knew Davison, described her as "a fanatic" who was prepared to die but did not mean to.[119] Other observers, such as Purvis, and Ann Morley and Liz Stanley—Davison's biographers—agree that Davison did not mean to die.[120][121]

Davison was a staunch feminist and a passionate Christian[122][123] whose outlook "invoked both medieval history and faith in God as part of the armour of her militancy".[124] Her love of English literature, which she had studied at Oxford, was shown in her identification with Geoffrey Chaucer's The Knight's Tale, including being nicknamed "Faire Emelye".[125][126] Much of Davison's writing reflected the doctrine of the Christian faith and referred to martyrs, martyrdom and triumphant suffering; according to Collette, the use of Christian and medieval language and imagery "directly reflects the politics and rhetoric of the militant suffrage movement". Purvis writes that Davison's committed Anglicanism would have stopped her from committing suicide because it would have meant that she could not be buried in consecrated ground.[124][127] Davison wrote in "The Price of Liberty" about the high cost of devotion to the cause:

In the New Testament, the Master reminded His followers that when the merchant had found the Pearl of Great Price, he sold all that he had in order to buy it. That is the parable of Militancy! It is that which the women warriors are doing to-day.

Some are truer warriors than others, but the perfect Amazon is she who will sacrifice all even unto the last, to win the Pearl of Freedom for her sex.[101][128]

Davison held a firm moral conviction that socialism was a moral and political force for good.[129] She attended the annual May Day rallies in Hyde Park and, according to the historian Krista Cowman, "directly linked her militant suffrage activities with socialism".[130] Her London and Morpeth funeral processions contained a heavy socialist presence in appreciation of her support for the cause.[130]

Legacy

In 1968 a one-act play written by Joice Worters, Emily, was staged in Northumberland, focusing on the use of violence against the women's campaign.[131] Davison is the subject of an opera, Emily (2013), by the British composer Tim Benjamin, and of "Emily Davison", a song by the American rock singer Greg Kihn.[132] Davison also appears as a supporting character in the 2015 film Suffragette, in which she is portrayed by Natalie Press. Her death and funeral form the climax of the film.[133] In January 2018 the cantata Pearl of Freedom, telling the story of Davison's suffragette struggles, was premiered. The music was by the composer Joanna Marsh; the librettist was David Pountney.[134]

In 1990 the Labour MPs Tony Benn and Jeremy Corbyn placed a commemorative plaque inside the cupboard in which Davison had hidden eighty years earlier.[135][136] In April 2013 a plaque was unveiled at Epsom racecourse to mark the centenary of her death.[137] In January 2017 Royal Holloway announced that its new library would be named after her.[138] The statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, unveiled in April 2018, features Davison's name and picture, along with those of 58 other women's suffrage supporters, on the plinth of the statue.[139] The Women's Library, at the London School of Economics, holds several collections related to Davison. They include her personal papers and objects connected to her death.[75] In June 2023 English Heritage unveiled a blue plaque at 43 Fairholme Road, Kensington, London where she lived when at Kensington High School in 1880s.[140][141] A statue of Davison, by the artist Christine Charlesworth, was installed in the marketplace at Epsom in 2021, following a campaign by volunteers from the Emily Davison Memorial Project.[142]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- ^ £20 in 1892 equates to approximately £2,300 in 2021 pounds, according to calculations based on Consumer Price Index measure of inflation.[8]

- ^ At the time of Davison's studies, Holloway was not a constituent school of the University of London and could not award degrees, so her studies were for the qualification of the Oxford Honour School.[10]

- ^ Sources differ over the subject of her degree. Some state that she studied modern languages,[1][14] others that she graduated in classics and mathematics.[15][16]

- ^ Such tactics included vandalism, arson and planting bombs.[18]

- ^ Although some sources, including Colmore and Purvis, state that Davison was employed in the Information Department of the union, the journalist Fran Abrams writes that Davison was never a salaried member of WSPU staff, but she was paid for the articles she provided for Votes for Women.[43]

- ^ Despite the loss of the Conciliation Bill, the WSPU maintained the truce until May 1911 when a second Conciliation Bill, having passed its Second Reading, was dropped by the government for internal political reasons. The WSPU saw this as a betrayal and resumed their militant activities.[48]

- ^ Davison also spent a night in the Palace of Westminster in June 1911.[23]

- ^ Craganour, the bookmakers' favourite, crossed the finishing line first, but a stewards' enquiry led to the horse being placed last and the race being awarded to Aboyeur, a 100/1 outsider.[68]

- ^ One letter, signed "An Englishman", read "I am glad that you are in hospital. I hope you suffer torture until you die, you idiot. ... I should like the opportunity of starving and beating you to a pulp."[71][72]

- ^ The presence of a return ticket was seen as evidence that Davison did not mean to commit suicide; research by Crawford showed that on Derby day, only return tickets were available.[77]

- ^ Carolyn Collette, a literary critic who has studied Davison's writing, observes that there have long been stories of Davison practising at grabbing bridles of horses, but these are all unconfirmed.[87]

- ^ The Cat and Mouse Act—officially the Prisoners (Temporary Discharge for Ill Health) Act 1913—was introduced by the Liberal government to counter the suffragette tactic of hunger strikes. The act allowed the prisoners to be released on licence as soon as the hunger strike affected their health, then to be re-arrested when they had recovered to finish their prison sentences.[106]

- ^ To be able to vote women had to be householders or the wives of householders, or pay more than £5 a year in rent, or be a graduate of a British university. Practically all the property qualifications for men were abolished by the act.[110]

References

- ^ a b c d e San Vito 2008.

- ^ Sleight 1988, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Howes 2013, 410–422.

- ^ Sleight 1988, pp. 22–24.

- ^ Tanner 2013, p. 156.

- ^ Colmore 1988, pp. 5, 9.

- ^ Sleight 1988, pp. 26–27.

- ^ UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ Colmore 1988, p. 15.

- ^ Abrams 2003, p. 161.

- ^ a b c Crawford 2003, p. 159.

- ^ Tanner 2013, p. 160.

- ^ Sleight 1988, pp. 28–30.

- ^ a b Tanner 2013, p. 161.

- ^ Gullickson 2008, p. 464.

- ^ a b Purvis 2013a, p. 354.

- ^ Naylor 2011, p. 18.

- ^ Webb 2014, pp. xiii–xiv, 60.

- ^ Sleight 1988, p. 32.

- ^ Pankhurst 2013, 6363.

- ^ a b Naylor 2011, p. 19.

- ^ a b Crawford 2003, p. 160.

- ^ a b c d e A. J. R. 1913, p. 221.

- ^ Tanner 2013, p. 167.

- ^ Davison, Votes for Women, 1909.

- ^ Colmore 1988, pp. 21–22.

- ^ a b Gullickson 2008, p. 465.

- ^ Colmore 1988, p. 24.

- ^ Davison, The Manchester Guardian, 1909.

- ^ Bearman 2007, p. 878.

- ^ Colmore 1988, pp. 24–25.

- ^ Stanley 1995, p. 236.

- ^ Purvis 2013a, p. 355.

- ^ Collette 2013, p. 133.

- ^ Gullickson 2008, pp. 468–469.

- ^ Collette 2013, pp. 133–135.

- ^ Hardie, 1909.

- ^ Colmore 1988, pp. 32–33.

- ^ Sleight 1988, pp. 42–43.

- ^ "Emily Wilding Davison found hiding in a ventilation shaft".

- ^ Colmore 1988, pp. 36–37.

- ^ Purvis 2013a, p. 356.

- ^ Abrams 2003, p. 167.

- ^ Foot 2005, pp. 210–211.

- ^ Gullickson 2008, p. 470.

- ^ Purvis 2002, p. 150.

- ^ Crawford 2003, p. 161.

- ^ Foot 2005, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Liddington, Crawford & Maund 2011, pp. 108, 124.

- ^ "A Night in Guy Fawkes Cupboard", Votes For Women, 1911.

- ^ Collette 2013, p. 173.

- ^ Tanner 2013, p. 183.

- ^ Crawford 2014, pp. 1006–1007.

- ^ Colmore 1988, pp. 43–44.

- ^ a b Davison 1913, p. 577.

- ^ Cawthorne 2017.

- ^ Davison 1912, p. 4.

- ^ Pankhurst 2013, 9029.

- ^ Morley & Stanley 1988, p. 74.

- ^ Purvis 2013a, p. 357.

- ^ West 1982, p. 179.

- ^ Colmore 1988, pp. 56–57.

- ^ a b Purvis 2013b.

- ^ a b Tanner 2013, pp. 214–215.

- ^ a b Secrets of a Suffragette, 26 May 2013, Event occurs at 35:10–36:06.

- ^ Tanner 2013, p. 278.

- ^ Secrets of a Suffragette, 26 May 2013, Event occurs at 2:10–2:15.

- ^ Tanner 2013, pp. 224, 243–244.

- ^ Morley & Stanley 1988, p. 103.

- ^ Tanner 2013, pp. 284–285.

- ^ Tanner 2013, p. 285.

- ^ Secrets of a Suffragette, 26 May 2013, Event occurs at 42:10–42:40.

- ^ a b c d Thorpe 2013.

- ^ Morley & Stanley 1988, pp. 103–104.

- ^ a b "Exhibitions: Emily Wilding Davison Centenary".

- ^ a b Greer 2013.

- ^ Crawford 2014, pp. 1001–1002.

- ^ Tanner 2013, pp. 281–282.

- ^ Tanner 2013, pp. 276–277.

- ^ "Suffragette and the King's Horse", The Manchester Guardian.

- ^ Tanner 2013, p. 287.

- ^ a b c "The Suffragist Outrage at the Derby", The Times.

- ^ a b "Miss Davison's Death", The Manchester Guardian.

- ^ Gullickson 2008, p. 473.

- ^ Brown 2013.

- ^ Crawford 2014, p. 1000.

- ^ Collette 2013, p. 21.

- ^ Tanner 2013, pp. 344–345.

- ^ Tanner 2013, pp. 278–279.

- ^ Tanner 2013, pp. 289–290.

- ^ a b Tanner 2013, p. 282.

- ^ Gullickson 2016, p. 10.

- ^ "The Distracting Derby", The Pall Mall Gazette.

- ^ "The Derby of Disasters", Daily Express.

- ^ "Woman's Mad Attack on the King's Derby Horse", The Daily Mirror.

- ^ a b Purvis 2013a, p. 358.

- ^ a b Gullickson 2008, p. 462.

- ^ "In Honour and Loving Memory of Emily Wilding Davison", The Suffragette.

- ^ "The Supreme Sacrifice", The Suffragette.

- ^ Gullickson 2008, p. 474.

- ^ a b Davison 1914, p. 129.

- ^ "The Funeral of Miss Davison", The Times.

- ^ a b c d "Miss Davison's Funeral", The Manchester Guardian.

- ^ a b Crawford 2003, p. 162.

- ^ Sleight 1988, p. 84.

- ^ "1913 Cat and Mouse Act".

- ^ "Miss Davison's Funeral", Votes for Women.

- ^ Sleight 1988, p. 100.

- ^ Tanner 2013, facing p. 172.

- ^ a b Purvis 1995, p. 98.

- ^ Collette 2013, p. 31.

- ^ Pugh 1974, p. 360.

- ^ "Archives – The Suffragettes".

- ^ Purvis 1995, pp. 98–99.

- ^ "Representation of the People Act 1918".

- ^ "Equal Franchise Act 1928".

- ^ Purvis 1995, p. 99.

- ^ a b Collette 2008, pp. 223–224.

- ^ Crawford 2003, p. 163.

- ^ Purvis 2013a, p. 359.

- ^ Morley & Stanley 1988, p. 65.

- ^ Gullickson 2016, p. 15.

- ^ Purvis 2013a, p. 360.

- ^ a b Collette 2012, p. 170.

- ^ Colmore 1988, p. 11.

- ^ Collette 2008, p. 226.

- ^ Purvis 2013c, p. 49.

- ^ Collette 2012, p. 172.

- ^ Morley & Stanley 1988, pp. 169–170.

- ^ a b Cowman 2002, p. 142.

- ^ Sleight 1988, p. 102.

- ^ Hall 2015, p. 4.

- ^ Blair 2016.

- ^ Marsh 2018.

- ^ Benn 2014, pp. xiii–xiv.

- ^ "Benn's Secret Tribute to Suffragette Martyr", BBC.

- ^ Barnett 2013.

- ^ "Emblem of women's emancipation", Royal Holloway, University of London.

- ^ "Mayor Marks Centenary of Women's Suffrage", Mayor of London.

- ^ "2023 Blue Plaques". English Heritage.

- ^ "Emily Wilding Davison". English Heritage.

- ^ Jenkinson 2021.

Sources

- "1913 Cat and Mouse Act". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 17 July 2017. Retrieved 12 July 2017.

- "2023 Blue Plaques". English Heritage. Retrieved 27 January 2023.

- Abrams, Fran (2003). Freedom's Cause. London: Profile Books. ISBN 978-1-8619-7425-9.

- A. J. R., ed. (1913). The Suffrage Annual and Women's Who's Who. London: S. Paul & Company. OCLC 7550282.

- "Archives – The Suffragettes". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 31 March 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- Balding, Clare (26 May 2013). Secrets of a Suffragette (Television production). Channel 4.

- Barnett, Emma (18 April 2013). "Centenary of Emily Wilding Davison's Death Marked with Plaque at Epsom". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Bearman, C. J. (December 2007). "An Army without Discipline? Suffragette Militancy and the Budget Crisis of 1909". The Historical Journal. 50 (4): 861–889. doi:10.1017/S0018246X07006413. JSTOR 20175131.

- Benn, Tony (2014). The Best of Benn. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1-4735-1801-8.

- "Benn's Secret Tribute to Suffragette Martyr". BBC News. 17 March 1999. Archived from the original on 14 March 2007. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- Blair, Olivia (1 March 2016). "International Women's Day 2016: Who was Emily Davison, the suffragette who ran in front of the King's Horse?". The Independent. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- Brown, Jonathan (24 May 2013). "Suffragette Emily Davison: The woman who would not be silenced". The Independent. Archived from the original on 22 June 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2017.

- Cawthorne, Ellie (17 April 2017). "Emily Davison: the Suffragette Martyr". BBC History. Archived from the original on 29 June 2017. Retrieved 5 July 2017.

- Collette, Carolyn (2008). ""Faire Emelye": Medievalism and the Moral Courage of Emily Wilding Davison". The Chaucer Review. 42 (3): 223–243. doi:10.1353/cr.2008.0001. JSTOR 25094399. S2CID 162949846.

- Collette, Carolyn (September 2012). "Hidden in Plain Sight: Religion and Medievalism in the British Women's Suffrage Movement". Religion & Literature. 44 (3): 169–175. JSTOR 24397755.

- Collette, Carolyn (2013). In the Thick of the Fight: The Writing of Emily Wilding Davison, Militant Suffragette. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11903-5.

- Colmore, Gertrude (1988) [1913]. "The Life of Emily Davison". In Morley, Ann; Stanley, Liz (eds.). The Life and Death of Emily Wilding Davison. London: The Women's Press. ISBN 978-0-7043-4133-3.

- Cowman, Krista (2002). "'Incipient Toryism'? The Women's Social and Political Union and the Independent Labour Party, 1903–14". History Workshop Journal. 53 (1): 128–148. doi:10.1093/hwj/53.1.128. JSTOR 4289777.

- Crawford, Elizabeth (2003). The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866–1928. London: UCL Press. ISBN 978-1-135-43402-1. Archived from the original on 27 July 2020. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- Crawford, Elizabeth (2014). "Emily Wilding Davison: centennial celebrations". Women's History Review. 23 (6): 1000–1007. doi:10.1080/09612025.2014.906961. S2CID 162816569.

- Davison, Emily (11 June 1909). "Letters". Votes for Women. p. 781.

- Davison, Emily (11 September 1909). "The 'Real Meaning' of the White City Disturbances". The Manchester Guardian. p. 5.

- Davison, Emily (19 September 1912). "'G.B.S.' and the Suffragettes". The Pall Mall Gazette. p. 4.

- Davison, Emily (13 June 1913). "A Year Ago. A Statement by Miss Emily Wilding Davison on her Release From Holloway, June 1912". The Suffragette: 577.

- Davison, Emily (5 June 1914). "The Price of Liberty". The Suffragette. p. 129. Archived from the original on 4 June 2021. Retrieved 4 June 2021.

- "The Derby of Disasters". Daily Express. 5 June 1913. p. 1.

- "The Distracting Derby". The Pall Mall Gazette. 5 June 1913. p. 8.

- "Emblem of women's emancipation, Emily Wilding Davison celebrated by landmark new Library and Student Services Centre". Royal Holloway, University of London. 11 January 2017. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 15 June 2017.

- "Emily Wilding Davison". English Heritage. Retrieved 4 June 2023.

- "Emily Wilding Davison Found Hiding in a Ventilation Shaft". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 10 May 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- "Equal Franchise Act 1928". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- "Exhibitions: Emily Wilding Davison Centenary". London School of Economics. Archived from the original on 22 June 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

- Foot, Paul (2005). The Vote: How it Was Won, and How it Was Undermined. London: Viking. ISBN 978-0-6709-1536-1.

- "The Funeral of Miss Davison". The Times. 13 June 1913. p. 3.

- Greer, Germaine (1 June 2013). "Emily Davison: was she really a suffragette martyr?". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 3 December 2017. Retrieved 5 April 2018.

- Gullickson, Gay L. (2008). "Emily Wilding Davison: Secular Martyr?". Social Research. 75 (2): 461–484. doi:10.1353/sor.2008.0037. JSTOR 40972072. S2CID 201776722.

- Gullickson, Gay L. (October 2016). "When Death Became Thinkable: Self-Sacrifice in the Women's Social and Political Union". Journal of Social History: shw102. doi:10.1093/jsh/shw102. S2CID 201703568. Cited page numbers from the pdf version.

- Hardie, Keir (1 November 1909). "Use of Water Hose". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons. col. 1432–1434.

- Hall, Janet (23 October 2015). "Ten things to learn about Morpeth Suffragette Emily Davison". Northumberland Gazette. p. 4.

- "In Honour and Loving Memory of Emily Wilding Davison". The Suffragette. 13 June 1913. p. 1.

- Howes, Maureen (2013). Emily Wilding Davison: A Suffragette's Family Album (Kindle ed.). Stroud, Glos: The History Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-9802-7.

- Jenkinson, Orlando (8 June 2021). "Emily Davison statue unveiled in Epsom". Surrey Comet. Retrieved 9 June 2021.

- Liddington, Jill; Crawford, Elizabeth; Maund, E. A. (Spring 2011). "'Women Do Not Count, Neither Shall They Be Counted': Suffrage, Citizenship and the Battle for the 1911 Census". History Workshop Journal (17): 98–127. ISSN 4130-6813.

- Marsh, Joanna (31 January 2018). "Warrior woman: my cantata for suffragette Emily Davison". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 February 2018. Retrieved 3 February 2018.

- "Mayor Marks Centenary of Women's Suffrage". Mayor of London. 6 February 2018. Archived from the original on 26 April 2018. Retrieved 26 April 2018.

- "Miss Davison's Death: Inquest and Verdict". The Manchester Guardian. 11 June 1913. p. 9.

- "Miss Davison's Funeral: Impressive London Procession". The Manchester Guardian. 16 June 1913. p. 9.

- "Miss Davison's Funeral". Votes for Women. 20 June 1913. p. 553.

- Morley, Ann; Stanley, Liz (1988). The Life and Death of Emily Wilding Davison. London: The Women's Press. ISBN 978-0-7043-4133-3.

- Naylor, Fay (2011). "Emily Wilding Davison: Martyr or Firebrand?" (PDF). Higher Magazine. Royal Holloway, University of London. Archived (PDF) from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- "A Night in Guy Fawkes Cupboard". Votes For Women. 7 April 1911. p. 441.

- Pankhurst, Sylvia (2013) [1931]. The Suffragette Movement: An Intimate Account of Persons and Ideals (Kindle ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Wharton Press. ISBN 978-1-4465-1043-8.

- Pugh, Martin D. (1974). "Politicians and the Woman's Vote 1914–1918". History. 59 (197): 358–374. doi:10.1111/j.1468-229X.1974.tb02222.x.

- Purvis, June (March 1995). ""Deeds, Not Words": The Daily Lives of Militant Suffragettes in Edwardian Britain". Women's Studies International Forum. 18 (2): 91–101. doi:10.1016/0277-5395(94)00064-6.

- Purvis, June (2002). Emmeline Pankhurst: A Biography. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-23978-3.

- Purvis, June (2013a). "Remembering Emily Wilding Davison (1872–1913)". Women's History Review. 22 (3): 353–362. doi:10.1080/09612025.2013.781405. S2CID 163114123. Archived from the original on 2 March 2021. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Purvis, June (2013b). "The 1913 Death of Emily Wilding Davison was a Key Moment in the Ongoing Struggle for Gender Equality in the UK". Democratic Audit. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- Purvis, June (June 2013c). "The Suffragette Martyr". History. 14 (6): 46–49.

- "Representation of the People Act 1918". UK Parliament. Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 16 July 2017.

- San Vito, Vera Di Campli (2008). "Davison, Emily Wilding (1872–1913)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/37346. Retrieved 15 June 2017. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Sleight, John (1988). One-way Ticket to Epsom: Journalist's Enquiry into the Heroic Story of Emily Wilding Davison. Morpeth, Northumberland: Bridge Studios. ISBN 978-0-9512-6302-0.

- Stanley, Liz (1995). The Auto/biographical I: The Theory and Practice of Feminist Auto/biography. Manchester: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4649-0.

- "Suffragette and the King's Horse: Interview with the Jockey". The Manchester Guardian. 6 June 1913. p. 9.

- "The Suffragist Outrage at the Derby". The Times. 11 June 1913. p. 15.

- "The Supreme Sacrifice". The Suffragette. 13 June 1913. pp. 578–579.

- Tanner, Michael (2013). The Suffragette Derby. London: The Robson Press. ISBN 978-1-8495-4518-1.

- Thorpe, Vanessa (26 May 2013). "Truth Behind the Death of Suffragette Emily Davison is Finally Revealed". The Observer. Archived from the original on 13 July 2014. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- Webb, Simon (2014). The Suffragette Bombers: Britain's Forgotten Terrorists. Barnsley, S Yorks: Pen and Sword. ISBN 978-1-78340-064-5.

- West, Rebecca (1982). The Young Rebecca: Writings of Rebecca West, 1911–17. New York: Viking Press. ISBN 978-0-670-79458-4.

- "Woman's Mad Attack on the King's Derby Horse". The Daily Mirror. 5 June 1913. p. 4.

External links

- An exhibit on Emily Davison, London School of Economics.

- The original Pathé footage of Emily Davison running out of the crowds at the Derby

- "Emily Wilding Davison". Find a Grave. 11 April 2005. Retrieved 18 August 2011.

- BBC profile

- Archives of Emily Davison at the Women's Library at the Library of the London School of Economics

- "The Price of Liberty" manuscript (1913) at Google Arts & Culture