PSR B1257+12 C

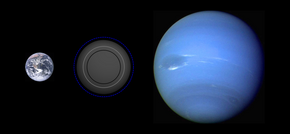

Size comparison of Phobetor with Earth and Neptune

(Based on selected hypothetical modeled compositions) | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Aleksander Wolszczan |

| Discovery site | Poland |

| Discovery date | 22 January 1992 |

| Pulsar Timing | |

| Orbital characteristics | |

| 0.46 AU (69 million km)[1] | |

| Eccentricity | 0.0252 ± 0.0002[1] |

| 98.2114 ± 0.0002[1] d | |

| Inclination | 47 ± 3[1][note 1] |

| 2,449,766.5 ± 0.1[1] | |

| 108.3 ± 0.5[1] | |

| Star | Lich |

| Physical characteristics | |

Mean radius | ~1.5 R🜨 |

| Mass | 3.9 (± 0.2)[1] ME |

| Temperature | 169 K (−104 °C; −155 °F)[2] |

| |

PSR B1257+12 C, alternatively designated PSR B1257+12 d and also named Phobetor, is a super-Earth exoplanet orbiting the pulsar Lich approximately 2,315 light-years (710 parsecs; 22 quadrillion kilometres) away from Earth in the constellation of Virgo. It was one of the first planets ever discovered outside the Solar System. It was discovered using the pulsar timing method, where the regular pulses of a pulsar are measured to determine if there is a planet causing variations in the data.

In July 2014 the International Astronomical Union (IAU) launched NameExoWorlds, a process for giving proper names to certain exoplanets and their host stars.[3] The process involved public nomination and voting for the new names.[4] In December 2015, the IAU announced the winning name was Phobetor for this planet.[5][6] The winning name was submitted by the Planetarium Südtirol Alto Adige in Karneid, Italy. Phobetor is, in Ovid's Metamorphoses, one of the thousand sons of Somnus (Sleep) who appears in dreams in the form of beasts.[7]

Characteristics

Mass, radius and temperature

Phobetor is a super-Earth, an exoplanet that has a radius and mass larger than that of Earth. It has an equilibrium temperature of 567 K (294 °C; 561 °F).[8] It has a mass of 3.9 ME and a likely radius of 1.5 R🜨, based on its mass.

Host star

The planet orbits a pulsar named Lich. The stellar remnant has a mass of 1.4 M☉ and a radius of around 0.000015 R☉ (10 kilometres). It has a surface temperature of ≤28,856 K and is one billion years old, with a small margin of error. In comparison, the Sun is about 4.6 billion years old[9] and has a surface temperature of 5,778 K.[10]

The star's apparent magnitude, or how bright it appears from Earth's perspective, is 12.2. Therefore, it is too dim to be seen with the naked eye.

Orbit

Phobetor orbits its host star about every 98 days at a distance of 0.46 AU (close to the orbital distance of Mercury from the Sun, which is 0.38 AU).

Formation

When Phobetor and its neighbors were discovered, scientists were puzzled on how the planets formed. Normally, planets orbiting around a massive star would evaporate when its host star exploded in a supernova due to the intense heat (up to 1,000,000 K) and radiation.

Several theories have been proposed for how the planets around Lich formed. One theory suggested that the planets actually had existed before the host star exploded in a supernova about 1 billion years ago; however, this is inconsistent as the ejected material from a supernova would be enough to vaporize any planets close to the star. Also, multiple issues arise with this theory that debates nearly impossible steps on how the planets ended up in their current places. Thus, the scenario has been dropped.[11]

One scenario proposed a massive binary system in which the planets formed around, with the more massive companion exploding in a supernova. The neutron star would then orbit the secondary companion (forming an X-ray binary) until the now-red supergiant exceeded its Roche lobe and began spilling material onto the neutron star, with the transfer being so dramatic that it forms a Thorne–Żytkow object. However, this doesn't explain how the pulsar would reach a spin rate of 6 milliseconds, so the model is still being questioned.[11]

Another model stated that the planets might have formed from a fallback disk from the supernova remnant. The main problem is that the resulting pulsar would be a radio pulsar, not the kind of pulsar that PSR B1257+12 is. Thus, it is unlikely that this was how the planet formed.[11]

The most widely accepted model for the planets around Lich is that they were a result of two white dwarfs merging. The white dwarfs would be in a binary orbit, with the orbit slowly decaying until the lighter white dwarf star filled its Roche lobe. If the mass ratio is large, the lighter companion would be disrupted, forming a disk around the more massive companion. The star would accrete this material, and would result in its mass increasing until it reaches the Chandrasekhar limit, in which it would experience core collapse and turn into a rapidly rotating neutron star, or, to be precise, a pulsar. After the explosion, the disk around the pulsar would still be massive enough (about 0.1 M☉) to form planets, which would likely be terrestrial, due to them being composed of white dwarf material such as carbon and oxygen.[11]

Nomenclature

Phobetor, the common name for the planet, is the name of a character in Ovid's Metamorphoses. In Latin, phobetor literally means "frightener".

On its discovery, the planet was designated PSR 1257+12 C and later PSR B1257+12 C. It was discovered before the convention that extrasolar planets receive designations consisting of the star's name followed by lowercase Roman letters starting from "b" was established.[12] However, it is listed under the latter convention on astronomical databases such as SIMBAD and the Extrasolar Planets Encyclopedia. Hence the alternative designation PSR B1257+12 d.

The convention that arose for designating pulsars was that of using the letters PSR (Pulsating Source of Radio) followed by the pulsar's right ascension and degrees of declination. The modern convention prefixes the older numbers with a B meaning the coordinates are for the 1950.0 epoch. All new pulsars have a J indicating 2000.0 coordinates and also have declination including minutes. Pulsars that were discovered before 1993 tend to retain their B names rather than use their J names, but all pulsars have a J name that provides more precise coordinates of its location in the sky.[13]

See also

- List of exoplanets discovered before 2000 - SPR B1257+12 d

References

- ^ a b c d e f g Konacki, M.; Wolszczan, A. (2003). "Masses and Orbital Inclinations of Planets in the PSR B1257+12 System". The Astrophysical Journal. 591 (2): L147–L150. arXiv:astro-ph/0305536. Bibcode:2003ApJ...591L.147K. doi:10.1086/377093. S2CID 18649212.

- ^ Extrasolar Visions - PSR 1257+12 C Archived December 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ NameExoWorlds: An IAU Worldwide Contest to Name Exoplanets and their Host Stars. IAU.org. 9 July 2014

- ^ "NameExoWorlds The Process". Archived from the original on 2015-08-15. Retrieved 2015-09-05.

- ^ Final Results of NameExoWorlds Public Vote Released, International Astronomical Union, 15 December 2015.

- ^ The Proposals page for Mu Arae Archived 2017-04-05 at the Wayback Machine, International Astronomical Union, 2016-01-03.

- ^ Ovid, Metamorphoses 11.638–641.

- ^ http://www.hpcf.upr.edu/~abel/phl/hec_plots/hec_orbit/hec_orbit_PSR_1257_12_d.png [bare URL image file]

- ^ Fraser Cain (16 September 2008). "How Old is the Sun?". Universe Today. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ Fraser Cain (September 15, 2008). "Temperature of the Sun". Universe Today. Retrieved 19 February 2011.

- ^ a b c d Podsiadlowski, P. (1993). "Planet Formation Scenarios". Planets Around Pulsars; Proceedings of the Conference, California Inst. Of Technology, Pasadena, Apr. 30-May 1, 1992. 36: 149–165. Bibcode:1993ASPC...36..149P.

- ^ Hessman, F. V.; Dhillon, V. S.; Winget, D. E.; Schreiber, M. R.; Horne, K.; Marsh, T. R.; Guenther, E.; Schwope, A.; Heber, U. (2010). "On the naming convention used for multiple star systems and extrasolar planets". arXiv:1012.0707 [astro-ph.SR].

- ^ Lyne, Andrew G.; Graham-Smith, Francis. Pulsar Astronomy. Cambridge University Press, 1998.

- Wolszczan, A.; Frail, D. (1992). "A planetary system around the millisecond pulsar PSR1257 + 12". Nature. 355 (6356): 145–147. Bibcode:1992Natur.355..145W. doi:10.1038/355145a0. S2CID 4260368.