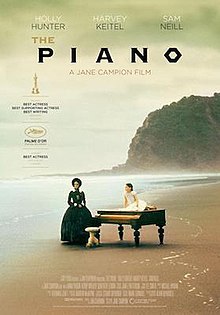

The Piano

| The Piano | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Jane Campion |

| Written by | Jane Campion |

| Produced by | Jan Chapman |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Stuart Dryburgh |

| Edited by | Veronika Jenet |

| Music by | Michael Nyman |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | BAC Films (France) Miramax[1] (Australia and New Zealand; through Buena Vista International[2] and Roadshow Film Distributors[3]) |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 117 minutes |

| Countries | New Zealand Australia France |

| Languages | English Māori British Sign Language |

| Budget | US$7 million[4] |

| Box office | US$140 million[5] |

The Piano is a 1993 historical drama film written and directed by New Zealand filmmaker Jane Campion. It stars Holly Hunter, Harvey Keitel, Sam Neill, and Anna Paquin in her first major acting role. The film focuses on a mute Scottish woman who travels to a remote part of New Zealand with her young daughter after her arranged marriage to a settler. The plot has similarities to Jane Mander's 1920 novel, The Story of a New Zealand River, but also substantial differences. Campion has cited the novels Wuthering Heights and The African Queen as inspirations.[6]

An international co-production between New Zealand, Australia, and France, The Piano was a critical and commercial success, grossing US$140.2 million worldwide (equivalent to $295.7 million in 2023) against its US$7 million budget (equivalent to $14.8 million in 2023). It was noted for its crossover appeal beyond the arthouse circuit to attracting mainstream popularity, largely due to rave reviews and word of mouth.[7]

Hunter and Paquin both received high praise for their performances. In 1993, the film won the Palme d'Or at the Cannes Film Festival, making Campion the first female director to receive the award. It won three Academy Awards out of eight total nominations in March 1994: Best Actress for Hunter, Best Supporting Actress for Paquin, and Best Original Screenplay for Campion. Paquin was 11 years old at the time and remains the second-youngest actor to win an Oscar in a competitive category.

Plot

In the mid-1800s,[8] Ada McGrath, a Scottish woman with elective mutism, travels to colonial New Zealand with her daughter Flora for an arranged marriage to settler Alisdair Stewart. Ada has not spoken since the age of six, and the reason for this as well as the identity of Flora's father remain unknown. She communicates through playing the piano and sign language, with Flora acting as her interpreter.

Ada and Flora, along with their handcrafted piano, are stranded on a New Zealand beach by a ship's crew. The next day, Alisdair arrives with his Māori crew and neighbour George Baines, a retired sailor who's adapted to Maori customs, including facial tattoos. Alisdair tells Ada that they don't have enough bearers for the piano and then refuses to go back for it, claiming that they all need to make sacrifices. Desperate to retrieve her piano, Ada seeks George's help. While at first saying no, he appears to give in due to her keenness on recovering the piano. Once at the beach, he is entranced by her music and appears charmed by her happy ways when she is playing, in contrast to her stern behaviour when in the farm.

George offers Alisdair the land he's been coveting in exchange for the piano and Ada's lessons. Alisdair agrees, oblivious to George's attraction to Ada. Ada is enraged by George's proposition but agrees to trade lessons for piano keys. She restricts the lessons to the black keys only and resists George's demands for more intimacy. Ada continues to rebuff Alisdair's advances while exploring her sensuality with George. George eventually realizes that Ada will never commit to him emotionally and returns the piano to her, confessing that he wants Ada to care for him genuinely.

Although Ada has her piano back, she longs for George and returns to him. Alisdair overhears them having sex and watches them through a crack in the wall. Furious, he confronts Ada and tries to force himself on her despite her strong resistance. He then coerces Ada into promising she will no longer see George.

Shortly after, Ada instructs Flora to deliver a package to George, which contains a piano key with a love declaration engraved on it. Flora delivers it to Alisdair instead. Enraged after reading the message, Alisdair cuts off Ada's index finger, depriving her of the ability to play the piano. He sends Flora to George with the severed finger, warning him to stay away from Ada or he will chop off more fingers. Later, while touching Ada as she sleeps, Alisdair hears what he thinks is her voice in his head, asking him to let George take her away. He goes to George's house and asks if Ada has ever spoken to him, but George says no. George and Ada leave together with her belongings and piano tied onto a Māori canoe. As they row to the ship, Ada asks George to throw the piano overboard. She allows her leg to be caught by the rope attached to the piano and is dragged underwater with it in an attempt to drown herself. As she sinks, she appears to change her mind and struggles free before being pulled to safety.

In the epilogue, Ada describes her new life with George and Flora in Nelson, New Zealand, where she gives piano lessons in their new home. George has made her a metal finger to replace the one she lost, and Ada has been practicing and taking speech lessons. She sometimes dreams of the piano resting at the bottom of the ocean with her still tethered to it.

Cast

- Holly Hunter as Ada McGrath

- Harvey Keitel as George Baines

- Sam Neill as Alisdair Stewart

- Anna Paquin as Flora McGrath

- Kerry Walker as Aunt Morag

- Genevieve Lemon as Nessie

- Tungia Baker as Hira

- Ian Mune as the Reverend

- Peter Dennett as the head seaman

- Cliff Curtis as Mana

- Pete Smith as Hone

- Te Whatanui Skipwith as Chief Nihe

- Mere Boynton as Nihe's daughter

- George Boyle as Ada's father

- Rose McIver as Angel

- Mika Haka as Tahu

- Gordon Hatfield as Te Kori

- Bruce Allpress as the blind piano tuner

- Stephen Papps as Bluebeard

Production

The film was originally titled The Piano Lesson, but the filmmakers could not obtain the rights to use the title because of the American play of the same name, and it was changed to The Piano.[9]

Casting the role of Ada was a difficult process. Sigourney Weaver was Campion's first choice, but she was not interested. Jennifer Jason Leigh was also considered, but had a conflict with her commitment to Rush (1991).[10] Isabelle Huppert met with Jane Campion and had vintage period-style photographs taken of her as Ada, and later said she regretted not fighting for the role as Hunter did.[11]

The casting for Flora occurred after Hunter had been selected for the part. They did a series of open auditions for girls age 9 to 13, focusing on girls who were small enough to be believable as Ada's daughter (as Holly Hunter is relatively short at 157 cm; 5 ft 2 in tall[12]). Anna Paquin ended up winning the role of Flora over 5,000 other girls.[13]

Alistair Fox has argued that The Piano was significantly influenced by Jane Mander's The Story of a New Zealand River.[14] Robert Macklin, an associate editor with The Canberra Times newspaper, has also written about the similarities.[15] The film also serves as a retelling of the fairytale "Bluebeard",[16][17] itself depicted as a scene in the Christmas pageant. Campion has cited the novels Wuthering Heights and The African Queen as inspirations.[6]

In July 2013, Campion revealed that she originally intended for the main character to drown in the sea after going overboard after her piano.[18]

Principal photography took place over 12 weeks from February to mid-May 1992.[19] The Piano was filmed in New Zealand’s North Island. The scene where Ada comes ashore and the piano is abandoned was filmed at Karekare Beach, west of Auckland. Bush scenes were filmed near Matakana and Awakino, while underwater scenes were filmed at the Bay of Islands.[20]

Campion was determined to market the film to appeal to a larger audience than the limited audiences many art films attracted at the time. Simona Benzakein, the publicist for The Piano at Cannes noted: "Jane and I discussed the marketing. She wanted this to be not just an elite film, but a popular film."[21]

Reception

Critical reception

Reviews for the film were overwhelmingly positive. Roger Ebert wrote: "The Piano is as peculiar and haunting as any film I've seen" and "it is one of those rare movies that is not just about a story, or some characters, but about a whole universe of feeling".[22] Hal Hinson of The Washington Post called it an "evocative, powerful, extraordinarily beautiful film".[23]

The Piano was named one of the best films of 1993 by 86 film critics, making it the most acclaimed film of 1993.[24]

In his 2013 Movie Guide, Leonard Maltin gave the film three and half out of four stars, calling the film a "haunting, unpredictable tale of love and sex told from a woman's point of view" and went on to say "writer-director Campion has fashioned a highly original fable, showing the tragedy and triumph erotic passion can bring to one's daily life".[25]

On review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film holds an approval rating of 90% based on 71 reviews, and an average rating of 8.50/10. The website's critical consensus reads: "Powered by Holly Hunter's main performance, The Piano is a truth-seeking romance played in the key of erotic passion."[26] On Metacritic, the film has a weighted average score of 89 out of 100, based on 20 critics, indicating "universal acclaim".[27]

Box office

The film was the highest-grossing New Zealand film of all-time surpassing Footrot Flats: The Dog's Tale (1986) with a gross of $NZ3.8 million.[28]

It grossed over US$140 million worldwide, including $7 million in Australia, $16 million in France, and $39 million in the United States and Canada.[29]

Accolades

The film was nominated for eight Academy Awards (including Best Picture), winning three for Best Actress (Holly Hunter), Best Supporting Actress (Anna Paquin) and Best Original Screenplay (Jane Campion). At age 11, Anna Paquin became the second youngest competitive Academy Award winner (after Tatum O'Neal in 1973).[30]

At the Cannes Film Festival, the film won the Palme d'Or (sharing with Chen Kaige's Farewell My Concubine), with Campion becoming the first woman to win the honour, as well as the first filmmaker from New Zealand to achieve this.[31][32] Holly Hunter also won Best Actress.[33]

In 2019, the BBC polled 368 film experts from 84 countries to name the 100 best films by women directors, and The Piano was named the top film, with nearly 10% of the critics polled giving it first place on their ballots.[34]

Soundtrack

The score for the film was written by Michael Nyman, and included the acclaimed piece "The Heart Asks Pleasure First"; additional pieces were "Big My Secret", "The Mood That Passes Through You", "Silver Fingered Fling", "Deep Sleep Playing" and "The Attraction of the Pedalling Ankle". This album is rated in the top 100 soundtrack albums of all time and Nyman's work is regarded as a key voice in the film, which has a mute lead character.[58]

Home media

The film was released on VHS on May 25, 1994. Initial fears in leadup to its release were in relation to the films status as "arty" and "non-mainstream," however its nominations and success at the Academy Awards guaranteed it profitability in the home video market.[59] It finished in the top 30 video rentals of 1994 in the United States.[60] It was released on DVD in 1997 by LIVE Entertainment and on Blu-ray on 31 January 2012 by Lionsgate, but already released in 2010 in Australia.[61]

On 11 August 2021, the Criterion Collection announced their first 4K Ultra HD releases, a six-film slate, will include The Piano. Criterion indicated each title would be available in a 4K UHD+Blu-ray combo pack, including a 4K UHD disc of the feature film as well as the film and special features on the companion Blu-ray. The Piano was released on January 25, 2022.[62]

See also

Footnotes

- ^ Tied with Farewell My Concubine.

- ^ Tied with Rosie Perez for Fearless.

- ^ Tied with Janusz Kamiński for Schindler's List.

References

- ^ "The Piano (1993)". Oz Movies. Retrieved 9 March 2024.

- ^ "Top 100 Australian Feature Films of All Time". Screen Australia. Retrieved 12 May 2023.

- ^ "The Piano (35mm)". Australian Classification Board. Retrieved 8 April 2023.

- ^ "Box Office Information for The Piano". TheWrap. Archived from the original on 11 December 2013. Retrieved 4 April 2013.

- ^ Margolis 2000, p. 135.

- ^ a b Frey, Hillary (September 2000). "Field Notes: The Purloined Piano?". Lingua Franca.

- ^ Elaine Margolis, Harriett (2000). Jane Campion's The Piano. Cambridge University Press. p. 32. ISBN 978-0521592581.

- ^ "The Piano review – Jane Campion's drama still hits all the right notes | The Piano". The Guardian. 15 June 2018. Retrieved 17 February 2022.

- ^ Bourguignon, Thomas; Ciment, Michel (1999) [1993]. "Interview with Jane Campion: More Barbarian than Aesthete". In Wexman, Virginia Wright (ed.). Jane Campion: Interviews. University Press of Mississippi. p. 109. ISBN 1-57806-083-4.

- ^ "A Pinewood Dialogue With Jennifer Jason Leigh" (PDF). Museum of the Moving Image. 23 November 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 July 2007.

- ^ "Isabelle Huppert: La Vie Pour Jouer – Career/Trivia". Archived from the original on 16 February 2012.

- ^ Worrell, Denise (21 December 1987). "Show Business: Holly Hunter Takes Hollywood". Time. Archived from the original on 23 December 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ^ Fish, Andrew (Summer 2010). "It's in Her Blood: From Child Prodigy to Supernatural Heroine, Anna Paquin Has Us Under Her Spell". Venice Magazine. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ^ Fox, Alistair. "Puritanism and the Erotics of Transgression: the New Zealand Influence on Jane Campion's Thematic Imaginary". Archived from the original on 24 October 2007. Retrieved 7 October 2007.

- ^ Macklin, Robert (September 2000). "FIELD NOTES: The Purloined Piano?". lingua franca. Vol. 10, no. 6.

- ^ Heiner, Heidi Ann. "Modern Interpretations of Bluebeard". Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Smith, Scott C. "Look at The Piano". Archived from the original on 12 October 2010. Retrieved 12 April 2010.

- ^ Child, Ben (8 July 2013). "Jane Campion wanted a bleaker ending for The Piano". The Guardian.

- ^ "'The Piano' Ain't Got No Wrong Notes". CineMontage. 12 June 2018. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ "The Piano 1993". Movie Locations. Retrieved 19 September 2024.

- ^ Elaine Margolis, Harriett (2000). Jane Campion's The Piano. Cambridge University Press. p. 136. ISBN 978-0521592581.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (19 November 1993). "The Piano". Rogerebert.com. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ Hinson, Hal (19 November 1993). "'The Piano' (R)". The Washington Post. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ McGilligan, Pat; Rowl, Mark (9 January 1994). "86 Thumbs Up! For Once, The Nation's Critics Agree on The Year's Best Movies". The Washington Post. Retrieved 13 December 2021.

- ^ Maltin, Leonard (2012). 2013 Movie Guide. Penguin Books. p. 1084. ISBN 978-0-451-23774-3.

- ^ "The Piano (1993)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 2 April 2022.

- ^ "The Piano Reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Groves, Don (29 August 1994). "Summer B.O. goes out like a 'Lion'". Variety. p. 14.

- ^ Margolis 2000.

- ^ Young, John (24 December 2008). "Anna Paquin: Did she really deserve an Oscar?". Entertainment Weekly.

- ^ Dowd, AA (13 February 2014). "1993 is the first and last time the Palme went to a woman". The A.V. Club. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ Margolis 2000, p. 1.

- ^ a b "The Piano". Cannes Film Festival. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "The 100 greatest films directed by women". BBC. 26 November 2019. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ^ "The 66th Academy Award Nominations : Oscars : The Nominees". Los Angeles Times. 10 February 1994. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2023.

"The 1994 Oscar Winners". The New York Times. 22 March 1994. Archived from the original on 22 December 2023. Retrieved 22 December 2023. - ^ "The ASC Awards for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography". Archived from the original on 2 August 2011.

- ^ "1993 Winners & Nominees". Australian Film Institute. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "Bodilprisen 1994". bodilprisen.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- ^ "Past Award Winners". Boston Society of Film Critics. 27 July 2018. Retrieved 15 November 2022.

- ^ "Film in 1994". British Academy of Film and Television Arts. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "Best Cinematography in Feature Film" (PDF). Retrieved 23 June 2021.

- ^ Williams, Michael (27 February 1994). "Resnais' 'Smoking' duo dominates Cesar prizes". Variety.

- ^ Terry, Clifford (8 February 1994). "Spielberg, 'List' Win in Chicago". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 29 September 2020. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "46th DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "1994 Film Critics Circle of Australia Awards". Mubi. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "The Piano – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "The Piano (1993)". Swedish Film Institute. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ "36 Years of Nominees and Winners" (PDF). Independent Spirit Awards. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ "Critics' Circle Film of the Year: 1980–2010". London Film Critics' Circle. 4 December 2010. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "London Film Critics Circle Awards 1994". Mubi. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "The 19th Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "1993 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. 19 December 2009. Retrieved 2 July 2017.

- ^ "1993 New York Film Critics Circle Awards". New York Film Critics Circle. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ Cox, Dan (19 January 1994). "Laurel noms announced". Variety.

- ^ "1993 SEFA Awards". sefca.net. Retrieved 15 May 2021.

- ^ Fox, David J. (14 March 1994). "'Schindler's' Adds a Pair to the List : Awards: Spielberg epic takes more honors—for screenwriting and editing. Jane Campion's 'The Piano' also wins". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- ^ "Top 100 Soundtrack Albums". Entertainment Weekly. 12 October 2001. p. 44.

- ^ Hunt, Dennis (11 February 1994). "Oscars Give Rentals New Lease on Life". Los Angeles Times.

- ^ "Top Video Rentals" (PDF). Billboard. 7 January 1995. p. 65.

- ^ Piano [Blu-ray] (1993)

- ^ Machkovech, Sam (11 August 2021). "Criterion announces support for 4K UHD Blu-ray, beginning with Citizen Kane". Ars Technica. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

Bibliography

- Margolis, Harriet (2000). Jane Campion's The Piano. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521597210. Retrieved 13 July 2016.

Further reading

- Althofer, Beth (1994). "The Piano, or Wuthering Heights revisited, or separation and civilization through the eyes of the (girl) child". Psychoanalytic Review. 81 (2): 339–342.

- Attwood, Feona (1998). "Weird Lullaby Jane Campion's "The Piano"". Feminist Review. 58 (1): 85–101. doi:10.1080/014177898339604. JSTOR 1395681. S2CID 144226880.

- Bentley, Greg (2002). "Mothers, daughters, and (absent) fathers in Jane Campion's The Piano". Literature/Film Quarterly. 30 (1): 46. ProQuest 226994856.

- Bihlmeyer, Jaime (2005). "The (Un) Speakable FEMININITY in Mainstream Movies: Jane Campion's" The Piano"". Cinema Journal. 44 (2): 68–88. doi:10.1353/cj.2005.0004. S2CID 191463102.

- Bihlmeyer, Jaime (2003). "Jane Campion's The Piano: The Female Gaze, the Speculum and the Chora within the H (y) st (e) rical Film" (PDF). Essays in Philosophy. 4 (1): 3–27. doi:10.5840/eip20034120.

- Bogdan, Deanne; Davis, Hilary; Robertson, Judith (1997). "Sweet Surrender and Trespassing Desires in Reading: Jane Campion's The Piano and the struggle for responsible pedagogy". Changing English. 4 (1): 81–103. doi:10.1080/1358684970040106.

- Bussi, Elisa (2000). "13 Voyages and Border Crossings: Jane Campion's "The Piano" (1993)". The Seeing Century. Brill: 161–173. doi:10.1163/9789004455030_014. ISBN 9789004455030. S2CID 239977351.

- Campion, Jane (2000). Jane Campion's The Piano. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521597210.

- Chumo II, Peter N. (1997). "Keys to the Imagination: Jane Campion's The Piano". Literature/Film Quarterly. 25 (3): 173.

- Dalton, Mary M.; Fatzinger, Kirsten James (2003). "Choosing silence: defiance and resistance without voice in Jane Campion's The Piano". Women and Language. 26 (2): 34.

- Davis, Michael (2002). "Tied to that Maternal 'Thing': Death and Desire in Jane Campion's "The Piano"". Gothic Studies. 4 (1): 63–78. doi:10.7227/GS.4.1.5.

- Dayal, Samir (2002). "Inhuman love: Jane Campion's "The Piano"". Postmodern Culture. 12 (2). doi:10.1353/pmc.2002.0005. S2CID 144838814.

- DuPuis, Reshela (1996). "Romanticizing Colonialism: Power and Pleasure in Jane Campion's "The Piano"". The Contemporary Pacific. 8 (1): 51–79. JSTOR 23706813.

- Frankenberg, Ronnie (2016). "Re-presenting the Embodied Child: the Muted Child, the Tamed Wife and the Silenced Instrument in Jane Campion's "The Piano"". The Body, Childhood and Society. Springer. p. 125. ISBN 978-0-333-98363-8.

- Frus, Phyllis (2010). "Borrowing a Melody: Jane Campion's "The Piano" and Intertextuality". In Frus, Phyllis; Williams, Christy (eds.). Beyond Adaptation: Essays on Radical Transformations of Original Works. McFarland. ISBN 978-0786442232.

- Gillett, Sue (1995). "Lips and fingers: Jane Campion's "The Piano"". Screen. 36 (3): 277–287. doi:10.1093/screen/36.3.277.

- Hazel, Valerie (1994). "Disjointed Articulations: The Politics of Voice and Jane Campion's "The Piano"" (PDF). Women's Studies Journal. 10 (2): 27.

- Hendershot, Cyndy (1998). "(Re) Visioning the Gothic: Jane Campion's "The Piano"". Literature/Film Quarterly. 26 (2): 97–108. JSTOR 43796833.

- Izod, John (1996). "The Piano, the Animus, and the Colonial Experience". Journal of Analytical Psychology. 41 (1): 117–136. doi:10.1111/j.1465-5922.1996.00117.x. PMID 8851259.

- Jacobs, Carol (December 1994). "Playing Jane Campion's Piano: Politically". Modern Language Notes. 109: 757–785.

- James, Caryn (28 November 1993). "A Distinctive Shade of Darkness". The New York Times. Retrieved 19 July 2023.

- Jayamanne, Laleen (2001). "Post-colonial gothic: the narcissistic wound of Jane Campion's "The Piano"". Toward Cinema and Its Double: Cross-cultural Mimesis. Indiana University Press: 24–48. ISBN 978-0253214751.

- Jolly, Margaret (2009). "Looking Back? Gender, Sexuality and Race in "The Piano"". Australian Feminist Studies. 24 (59): 99–121. doi:10.1080/08164640802680627. hdl:1885/31897. S2CID 143160100.

- Klinger, Barbara (2003). "Contested Endings: Interpreting The Piano's (1993) Final Scenes". Film Moments: Criticism, History, Theory: 135–39.

- Klinger, Barbara (2006). "The art film, affect and the female viewer: "The Piano" revisited". Screen. 47 (1): 19–41. doi:10.1093/screen/hjl002.

- Molina, Caroline (1997). "Muteness and mutilation: the aesthetics of disability in Jane Campion's "The Piano"". The Body and Physical Difference: Discourses of Disability. University of Michigan Press. pp. 267–282. ISBN 978-0472066599.

- Najita, Susan Yukie (2001). "Family Resemblances: The Construction of Pakeha History in Jane Campion's "The Piano"". ARIEL: A Review of International English Literature. 32 (1).

- Norgrove, Aaron (1998). "But is it music? The crisis of identity in "The Piano"". Race & Class. 40 (1): 47–56. doi:10.1177/030639689804000104. S2CID 143485321.

- Pflueger, Pennie (2015). "The Piano and Female Subjectivity: Kate Chopin's "The Awakening" (1899) and Jane Campion's "The Piano" (1993)". Women's Studies. 44 (4): 468–498. doi:10.1080/00497878.2015.1013213. S2CID 142988458.

- Preis-Smith, Agata (2009). "Was Ada McGrath a Cyborg, or, the Post-human Concept of the Female Artist in Jane Campion's "The Piano"" (PDF). Acta Philologica: 21.

- Reid, Mark A. (2000). "A few black keys and Maori tattoos: Re-reading Jane Campion's the piano in PostNegritude time". Quarterly Review of Film & Video. 17 (2): 107–116. doi:10.1080/10509200009361484. S2CID 191617268.

- Riu, Carmen Pérez (2000). "Two Gothic Feminist Texts: Emily Brontë's "Wuthering Heights" and the Film "The Piano" by Jane Campion". Atlantis: 163–173.

- Sklarew, Bruce H. (2018). "I Have Not Spoken: Silence in "The Piano"". In Gabbard, Glen O. (ed.). Psychoanalysis and Film. Routledge. pp. 115–120. ISBN 978-0429478703.

- Taylor, Lib (2014). "Inscription in "The Piano"". In Bignell, Jonathan (ed.). Writing and Cinema. Routledge. pp. 88–101. doi:10.4324/9781315839325. ISBN 978-1315839325.

- Thornley, Davinia (2000). "Duel or Duet? Gendered Nationalism in "The Piano"". Film Criticism. 24 (3): 61–76. JSTOR 44019061.

- Williams, Donald (2013). "The Piano: The Isolated, Constricted Self". Film Commentaries.

- Wrye, Harriet Kimble (1998). "Tuning a clinical ear to the ambiguous chords of Jane Campion's "The Piano"". Psychoanalytic Inquiry. 18 (2): 168–182. doi:10.1080/07351699809534182.

- Zarzosa, Agustin (2010). "Jane Campion's The Piano: melodrama as mode of exchange". New Review of Film and Television Studies. 8 (4): 396–411. doi:10.1080/17400309.2010.514664. S2CID 191596093.

External links

- The Piano at IMDb

- The Piano at the TCM Movie Database

- The Piano at Box Office Mojo

- The Piano at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Piano at Metacritic

- The Piano at Ozmovies

- The Piano: Gothic Gone South an essay by Carmen Gray at the Criterion Collection