The Last Emperor

| The Last Emperor | |

|---|---|

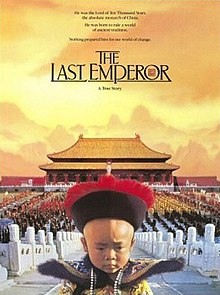

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Bernardo Bertolucci |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | From Emperor to Citizen: The Autobiography of Aisin-Gioro Puyi 1960 autobiography by Puyi |

| Produced by | Jeremy Thomas |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Vittorio Storaro |

| Edited by | Gabriella Cristiani |

| Music by |

|

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Columbia Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 163 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $23.8 million[3] |

| Box office | $44 million[4] |

The Last Emperor (Italian: L'ultimo imperatore) is a 1987 epic biographical drama film about the life of Puyi, the last Emperor of China. It is directed by Bernardo Bertolucci from a screenplay he co-wrote with Mark Peploe, which was adapted from Puyi's 1964 autobiography, and independently produced by Jeremy Thomas.[5]

The film depicts Puyi's life from his ascent to the throne as an infant to his imprisonment and political rehabilitation by the Chinese Communist Party. It stars John Lone in the eponymous role, with Peter O'Toole, Joan Chen, Ruocheng Ying, Victor Wong, Dennis Dun, Vivian Wu, Lisa Lu, and Ryuichi Sakamoto (who also composed the film score with David Byrne and Cong Su). It was the first Western feature film authorised by the People's Republic of China to film in the Forbidden City in Beijing.[3]

The Last Emperor premiered at the 1987 Tokyo International Film Festival, and was released in the United States by Columbia Pictures on November 18. It earned widespread positive reviews from critics and was also a commercial success. At the 60th Academy Awards, it won all nine Oscars it was nominated for, including Best Picture, Best Director, and Best Adapted Screenplay. It also won several other accolades, including three BAFTA Awards, four Golden Globe Awards, nine David di Donatello Awards, and a Grammy Award for its musical score. The film was converted into 3D and shown in the Cannes Classics section at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival.[6]

Plot

By 1950, the 44-year-old Puyi, former Emperor of China, has been in custody for five years since his capture by the Red Army during the Soviet invasion of Manchuria. In the recently established People's Republic of China, Puyi arrives as a political prisoner and war criminal at the Fushun Prison. Soon after his arrival, Puyi attempts suicide, but is quickly rescued and told he must stand trial.

42 years earlier, in 1908, a toddler Puyi is summoned to the Forbidden City by the dying Empress Dowager Cixi. After telling him that the previous emperor had died earlier that day, Cixi tells Puyi that he is to be the next emperor. After his coronation, Puyi, frightened by his new surroundings, repeatedly expresses his wish to go home, but is denied. Despite having scores of palace eunuchs and maids to wait on him, his only real friend is his wet nurse, Ar Mo.

As he grows up, his upbringing is confined entirely to the imperial palace and he is prohibited from leaving. One day, he is visited by his younger brother, Pujie, who tells him he is no longer Emperor and that China has become a republic; that same day, Ar Mo is forced to leave. In 1919, Reginald Johnston is appointed as Puyi's tutor and gives him a Western-style education, and Puyi becomes increasingly desirous to leave the Forbidden City. Johnston, wary of the courtiers' expensive lifestyle, convinces Puyi that the best way of achieving this is through marriage; Puyi subsequently weds Wanrong, with Wenxiu as a secondary consort.

Puyi then sets about reforming the Forbidden City, including expelling the palace eunuchs. However, in 1924, he himself is expelled from the palace and exiled to Tientsin following the Beijing Coup. He leads a decadent life as a playboy and Anglophile, and sides with Japan after the Mukden Incident. During this time, Wenxiu divorces him, but Wanrong remains and eventually succumbs to opium addiction. In 1934, the Japanese crown him "Emperor" of their puppet state of Manchukuo, though his supposed political supremacy is undermined at every turn. Wanrong gives birth to an illegitimate child, but the baby is murdered at birth by the Japanese and proclaimed stillborn. She is then taken to a clinic where her physical and mental state declines even further. Puyi remains the nominal ruler of the region until Japan's capitulation. He decides to surrender to the Americans but before he can leave, he is captured by the Soviet Red Army and handed over to the Chinese.

Under the Communist re-education program for political prisoners, Puyi is coerced by his interrogators to formally renounce his forced collaboration with the Japanese invaders during the Second Sino-Japanese War. After heated discussions with Jin Yuan, the warden of the Fushun Prison, and watching a film detailing the wartime atrocities committed by the Japanese, Puyi eventually recants and is considered rehabilitated by the government; he is subsequently released in 1959.

Several years later in 1967, Puyi has become a simple gardener who lives a peasant proletarian existence following the rise of Mao Zedong's cult of personality and the Cultural Revolution. On his way home from work, he happens upon a Red Guard parade, celebrating the rejection of landlordism by the communists. He sees Jin Yuan, now one of the political prisoners punished as an anti-revolutionary in the parade, forced to wear a dunce cap and a sandwich board bearing punitive slogans.

Puyi later visits the Forbidden City, now turned into a museum, where he meets an assertive young boy wearing the red scarf of the Pioneer Movement. The boy orders Puyi to step away from the throne, but Puyi proves that he was indeed the Son of Heaven before approaching the throne. Behind it, Puyi finds a 60-year-old pet cricket that he was given by palace official Chen Baochen on his coronation day and gives it to the child. Amazed by the gift, the boy turns to talk to Puyi, but finds that he has disappeared.

In 1987, a tour guide leads a group through the palace. Stopping in front of the throne, the guide sums up Puyi's life in a few, brief sentences, before concluding that he died in 1967.

Cast

- John Lone as Puyi (adult)

- Richard Vuu as Puyi (3 years old)

- Tijger Tsou as Puyi (8 years old)[1]

- Wu Tao as Puyi (15 years old)

- Joan Chen as Wanrong

- Peter O'Toole as Reginald Johnston

- Ying Ruocheng as Jin Yuan, the Detention Camp Governor

- Victor Wong as Chen Baochen

- Dennis Dun as Big Li

- Ryuichi Sakamoto as Masahiko Amakasu

- Maggie Han as Eastern Jewel (Yoshiko Kawashima)

- Ric Young as the Camp Interrogator

- Vivian Wu as Wenxiu

- Cary-Hiroyuki Tagawa as Chang

- Jade Go as Ar Mo

- Fumihiko Ikeda as Colonel Yoshioka

- Fan Guang as Pujie (adult), Puyi's younger brother

- Henry Kyi as Pujie (7 years old)

- Alvin Riley III as Pujie (14 years old)

- Lisa Lu as Empress Dowager Cixi

- Basil Pao as Prince Chun, Puyi's father.

- Dong Liang as Lady Consort Chun, Puyi's mother.

- Henry O as the Lord Chamberlain

Other cast members include Chen Kaige as the Captain of the Imperial Guard, Hideo Takamatsu as General Takashi Hishikari, Hajime Tachibana as the General's translator, Zhang Liangbin as the eunuch Big Foot, Huang Wenjie as the eunuch Hunchback, Chen Shu as Zhang Jinghui, Cheng Shuyan as Hiro Saga, Li Fusheng as Xie Jieshi, and Constantine Gregory as the Emperor's oculist.

Production

Development

Bernardo Bertolucci proposed the film to the Chinese government as one of two possible projects – the other was an adaptation of La Condition humaine (Man's Fate) by André Malraux. The Chinese preferred The Last Emperor. Producer Jeremy Thomas managed to raise the $25 million budget for his ambitious independent production single-handedly.[7] At one stage, he scoured the phone book for potential financiers.[8] Bertolucci was given complete freedom by the authorities to shoot in the Forbidden City, which had never before been opened up for use in a Western film. For the first ninety minutes of the film, Bertolucci and Storaro made full use of its visual splendour.[7]

Filming

19,000 extras were needed over the course of the film. The People's Liberation Army (PLA) was drafted in to accommodate.[9]

In a 2010 interview with Bilge Ebiri for Vulture.com, Bertolucci recounted the shooting of the Cultural Revolution scene:

Before shooting the parade scene, I put together four or five young directors whom I had met, [including] Chen Kaige — who also plays a part in the film, he's the captain of the guard — and Zhang Yimou. I asked them about the Cultural Revolution. And suddenly it was like I was watching a psychodrama: they started to act out and cry, it was extraordinary. I think there is a relationship between these scenes in The Last Emperor and in 1900. But many things changed between those two films, for me and for the world.[10]

Historical accuracy

British historian Alex von Tunzelmann wrote that the movie considerably downplays and misrepresents the Emperor's cruelty, especially during his youth.[11] As stated by Tunzelmann and Behr (author of the 1987 book The Last Emperor), Puyi engaged in sadistic abuse of palace servants and subordinates during his initial reign well in excess of what Bertolucci's movie portrays, frequently having eunuchs beaten for mild transgressions or no reason at all; in a demonstrative example, the young Emperor once conspired to force a eunuch to eat a cake full of iron filings simply to see the eunuch's reaction, which he was talked out of by his beloved wet nurse with some difficulty.[11][12] Tunzelmann states that most people worldwide who have heard of Puyi are likely to have an incorrect understanding of this aspect of the Emperor's reign, as the movie is much more popular globally than more accurate biographies.[11]

The film contains several other historical inaccuracies: in real life, Puyi left the Forbidden City when his mother died; as he recounts in his memoirs, he did not have sex with his wives; Puyi actually stopped the Japanese from killing the Empress's lover rather than let him be murdered; although the film mentions the Beijing Coup, it erroneously claims that the president fled the capital instead of being put under house arrest; the testimonies that Puyi gives to his Chinese interrogators were in fact given at the Tokyo Trials.[13][14][15]

Jeremy Thomas recalled the approval process for the screenplay with the Chinese government: "It was less difficult than working with the studio system. They made script notes and made references to change some of the names, then the stamp went on and the door opened and we came."[9]

Soundtrack

While not included on the album soundtrack, the following music was played in the film: "Am I Blue?" (1929), "Auld Lang Syne" (uncredited), and "China Boy" (1922, uncredited). The Northeastern Cradle Song was sung by Ar Mo twice in the film.

Release

Hemdale Film Corporation acquired all North American distribution rights to the film on behalf of producer Thomas,[16] who raised a large sum of the budget himself. Hemdale, in turn, licensed theatrical rights to Columbia Pictures, who were initially reluctant to release it, and only after shooting was completed did the head of Columbia agree to distribute The Last Emperor in North America.[3]

The Last Emperor opened in 19 theatres in Italy and grossed $265,000 in its first weekend. It expanded to 65 theatres in its second weekend and 93 in its third, increasing its weekend gross to $763,000 and grossing $2 million in its first 16 days. Six days after its Italian opening, it opened in Germany and grossed $473,000 in its first weekend from 50 theatres and $1.1 million in its first 10 days.[17] The film had an unusual run in US theatres. It did not enter the weekend box office top 10 until its twelfth week in which the film reached number 7 after increasing its gross by 168% from the previous week and more than tripling its theatre count (this was the weekend before it was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Picture). Following that week, the film lingered around the top 10 for 8 weeks before peaking at number 4 in its 22nd week (the weekend after winning the Oscar), increasing its weekend gross by 306% and nearly doubling its theatre count from 460 to 877, and spending 6 more weeks in the weekend box office top 10.[18] Were it not for this late push, The Last Emperor would have joined The English Patient, Amadeus, and The Hurt Locker as the only Best Picture winners to not enter the weekend box office top 5 since these numbers were first recorded in 1982.

The film was converted into 3D and shown in the Cannes Classics section at the 2013 Cannes Film Festival.[6]

Critical response

On Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 86% based on 124 reviews, with an average rating of 8.10/10. The site's critics consensus states: "While Bernardo Bertolucci's decadent epic never quite identifies the dramatic pulse of its protagonist, stupendous visuals and John Lone's ability to make passivity riveting give The Last Emperor a rarified grandeur."[19] Metacritic assigned the film a weighted average score of 76 out of 100 based on 15 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[20] Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "A-" on an A+ to F scale.[21]

Roger Ebert was notably enthusiastic in his praise of the film, awarding it four out of four:

"Bertolucci is able to make Pu Yi's imprisonment seem all the more ironic because this entire film was shot on location inside the People's Republic of China, and he was even given permission to film inside the Forbidden City — a vast, medieval complex covering some 250 acres (100 ha) and containing 9,999 rooms (only heaven, the Chinese believed, had 10,000 rooms). It probably is unforgivably bourgeois to admire a film because of its locations, but in the case of The Last Emperor the narrative cannot be separated from the awesome presence of the Forbidden City, and from Bertolucci's astonishing use of locations, authentic costumes, and thousands of extras to create the everyday reality of this strange little boy."[22]

Jonathan Rosenbaum compared The Last Emperor favorably to Steven Spielberg's Empire of the Sun:

"At best, apart from a few snapshots, Empire of the Sun teaches us something about the inside of one director's brain. The Last Emperor incidentally and secondarily does that too; but it also teaches us something about the lives of a billion people with whom we share this planet—and better yet, makes us want to learn still more about them."[23]

Editing out of Rape of Nanking scene for Japan

The Shochiku Fuji Company edited out a thirty-second sequence depicting the Rape of Nanjing before distributing it to Japanese theatres. Bertolucci had not given his consent for the cut, and was furious at the interference with his film, which he called "revolting". The company quickly restored the scene, blaming "confusion and misunderstanding" for the edit while opining that the Rape sequence was "too sensational" for Japanese moviegoers.[24]

Home media

Hemdale licensed its video rights to Nelson Entertainment, which released the film on VHS and Laserdisc.[16] The film also received a Laserdisc release in Australia in 1992, through Columbia Tri-Star Video. Years later, Artisan Entertainment acquired the rights to the film and released both the theatrical and extended versions on home video. In February 2008 The Criterion Collection (under license from now-rights-holder Thomas) released a four disc Director-Approved edition, again containing both theatrical and extended versions.[25] Criterion released a Blu-ray version on 6 January 2009.[25]

Accolades

Alternative versions

The film's theatrical release ran 163 minutes. Deemed too long to show in a single three-hour block on television but too short to spread out over two nights, an extended version was created which runs 218 minutes. Cinematographer Vittorio Storaro and director Bernardo Bertolucci have confirmed that this extended version was indeed created as a television miniseries and does not represent a true "director's cut".[43]

Home video

The Criterion Collection 2008 version of four DVDs adds commentary by Ian Buruma, composer David Byrne, and the Director's interview with Jeremy Isaacs (ISBN 978-1-60465-014-3). It includes a booklet featuring an essay by David Thomson, interviews with production designer Ferdinando Scarfiotti and actor Ying Ruocheng, a reminiscence by Bertolucci, and an essay and production-diary extracts from Fabien S. Gerard.

The film was for quite some time unavailable on DVD or Blu-Ray in its original 2.35:1 aspect ratio, as cinematographer Vittorio Storaro had insisted on a cropped 2:1 version that retroactively conforms the film to his Univisium standard. Copies of the film in its original ratio were then rare and sought after by fans of the film.

The film has since been restored in 4K and in its original 2.35:1 aspect ratio, and has been released on Blu-ray and UHD in 2023 in several countries using this 4K restoration.[44]

See also

- Big Shot's Funeral, a film with a plot that involves a fictional remake of The Last Emperor

- List of historical drama films set in Asia

References

- ^ a b "THE LAST EMPEROR (15)". British Board of Film Classification. 16 November 1987. Retrieved 29 March 2023.

- ^ "The Last Emperor (1987)". BFI. British Film Institute. Retrieved 8 May 2024.

- ^ a b c Love And Respect, Hollywood-Style, an April 1988 article by Richard Corliss in Time

- ^ "The Last Emperor". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 29 September 2016.

- ^ Variety film review; 7 October 1987.

- ^ a b "Cannes Classics 2013 line-up unveiled". Screen Daily. Retrieved 30 April 2013.

- ^ a b McCarthy, Todd (11 May 2009). "'The Last Emperor' - Variety Review". Variety. Retrieved 6 February 2013.

- ^ Jafaar, Ali (11 May 2009). "Producers team on 'Assassins' Redo". Variety. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ a b Lieberson, Sandy (11 April 2006). "Jeremy Thomas - And I'm still a fan". Berlinale Talent Campus. Archived from the original on 24 May 2010. Retrieved 7 April 2010.

- ^ Ebiri, Bilge. "Bernardo Bertolucci Dissects Ten of His Classic Scenes". Vulture. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ a b c Tunzelmann, Alex (16 April 2009). "The Last Emperor: Life is stranger, and nastier, than fiction". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 November 2015.

- ^ Behr, Edward (1987). The Last Emperor. Toronto: Futura.

- ^ Bernstein, Richard (8 May 1988). "Is 'The Last Emperor' Truth or Propaganda?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ "A HISTORIAN CRITIQUES 'EMPEROR'". Chicago Tribune. 7 January 1988. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ "The Last Emperor: life is stranger, and nastier, than fiction". the Guardian. 16 April 2009. Retrieved 9 January 2023.

- ^ a b "FindLaw's California Court of Appeal case and opinions". Findlaw. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ^ "The Last Emperor (advertisement)". Screen International. 14 November 1987. pp. 10–11.

- ^ The Last Emperor (1987) - Weekend Box Office Results Box Office Mojo

- ^ "The Last Emperor". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango Media. Retrieved 3 May 2024.

- ^ "The Last Emperor reviews". Metacritic. CBS Interactive. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- ^ "Home". CinemaScore. Retrieved 4 May 2024.

- ^ Ebert, Roger (9 December 1987). "The Last Emperor Movie Review (1987)". The Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ Rosenbaum, Jonathan (17 December 1987). "The China Syndrome". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 22 September 2018.

- ^ Chang, Iris (1997). The Rape of Nanking (book). Basic Books. p. 210. ISBN 0-465-06835-9.

- ^ a b The Last Emperor (1987) The Criterion Collect

- ^ "The 60th Academy Awards (1988) Nominees and Winners". Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences. Retrieved 31 July 2011.

- ^ "The ASC Awards for Outstanding Achievement in Cinematography". American Society of Cinematographers. Archived from the original on 2 August 2011.

- ^ "1988 Artios Awards". Casting Society of America. Retrieved 7 February 2019.

- ^ "BSFC Winners: 1980s". Boston Society of Film Critics. 27 July 2018. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1989". British Academy Film Awards. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ^ "Best Cinematography in Feature Film" (PDF). British Society of Cinematographers. Retrieved 3 June 2021.

- ^ "The 1988 Caesars Ceremony". César Awards. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Cronologia Dei Premi David Di Donatello". David di Donatello. Retrieved 27 June 2017.

- ^ "40th DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "The Last Emperor". Golden Globe Awards. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "31st Annual GRAMMY Awards". Grammy Awards. Retrieved 1 May 2011.

- ^ "The 13th Annual Los Angeles Film Critics Association Awards". Los Angeles Film Critics Association. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "1987 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "1998 Award Winners". National Board of Review. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Past Awards". National Society of Film Critics. 19 December 2009. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "1987 New York Film Critics Circle Awards". New York Film Critics Circle. Retrieved 5 July 2021.

- ^ "Awards Winners". Writers Guild of America Awards. Archived from the original on 5 December 2012. Retrieved 6 June 2010.

- ^ Kim Hendrickson (3 January 2008). "Final Cut". The Criterion Collection. Retrieved 19 December 2009.

- ^ "Review of The Last Emperor 2023 UK Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com.