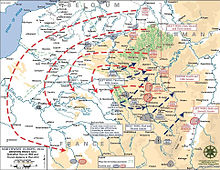

Schlieffen plan

| Schlieffen Plan | |

|---|---|

| Operational scope | Offensive strategy |

| Planned | 1905–1906 and 1906–1914 |

| Planned by | Alfred von Schlieffen Helmuth von Moltke the Younger |

| Objective | Disputed |

| Date | 7 August 1914 |

| Executed by | Moltke |

| Outcome | See Aftermath |

| Casualties | c. 305,000 |

The Schlieffen Plan (German: Schlieffen-Plan, pronounced [ʃliːfən plaːn]) is a name given after the First World War to German war plans, due to the influence of Field Marshal Alfred von Schlieffen and his thinking on an invasion of France and Belgium, which began on 4 August 1914. Schlieffen was Chief of the General Staff of the German Army from 1891 to 1906. In 1905 and 1906, Schlieffen devised an army deployment plan for a decisive (war-winning) offensive against the French Third Republic. German forces were to invade France through the Netherlands and Belgium rather than across the common border.

After losing the First World War, German official historians of the Reichsarchiv and other writers described the plan as a blueprint for victory. Generaloberst (Colonel-General) Helmuth von Moltke the Younger succeeded Schlieffen as Chief of the German General Staff in 1906 and was dismissed after the First Battle of the Marne (5–12 September 1914). German historians claimed that Moltke had ruined the plan by tampering with it, out of timidity. They managed to establish a commonly accepted narrative that Moltke the Younger failed to follow the blueprint devised by Schlieffen, condemning the belligerents to four years of attrition warfare.

In 1956, Gerhard Ritter published Der Schlieffenplan: Kritik eines Mythos (The Schlieffen Plan: Critique of a Myth), which began a period of revision, when the details of the supposed Schlieffen Plan were subjected to scrutiny. Treating the plan as a blueprint was rejected because this was contrary to the tradition of Prussian war planning established by Helmuth von Moltke the Elder, in which military operations were considered to be inherently unpredictable. Mobilisation and deployment plans were essential but campaign plans were pointless; rather than attempting to dictate to subordinate commanders, the commander gave the intent of the operation and subordinates achieved it through Auftragstaktik (mission tactics).

In writings from the 1970s, Martin van Creveld, John Keegan, Hew Strachan and others, studied the practical aspects of an invasion of France through Belgium and Luxembourg. They judged that the physical constraints of German, Belgian and French railways and the Belgian and northern French road networks made it impossible to move enough troops far enough and fast enough for them to fight a decisive battle if the French retreated from the frontier. Most of the pre-1914 planning of the German General Staff was secret and the documents were destroyed when deployment plans were superseded each April. The bombing of Potsdam in April 1945 destroyed much of the Prussian army archive and only incomplete records and other documents survived. Some records turned up after the fall of the German Democratic Republic (GDR), making an outline of German war planning possible for the first time, proving wrong much post-1918 writing.

In the 2000s, a document, RH61/v.96, was discovered in the trove inherited from the GDR, which had been used in a 1930s study of pre-war German General Staff war planning. Inferences that Schlieffen's war planning was solely offensive were found to have been made by extrapolating his writings and speeches on tactics into grand strategy. From a 1999 article in War in History and in Inventing the Schlieffen Plan (2002) to The Real German War Plan, 1906–1914 (2011), Terence Zuber engaged in a debate with Terence Holmes, Annika Mombauer, Robert Foley, Gerhard Gross, Holger Herwig and others. Zuber proposed that the Schlieffen Plan was a myth concocted in the 1920s by partial writers, intent on exculpating themselves and proving that German war planning did not cause the First World War. Later scholarship did not uphold the Zuber thesis except as a catalyst for research which revealed that Schlieffen had been far less dogmatic than had been assumed.

Background

Kabinettskrieg

After the end of the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars in 1815, European aggression had turned outwards and the fewer wars fought within the continent had been Kabinettskriege, local conflicts decided by professional armies loyal to dynastic rulers. Military strategists had adapted by creating plans to suit the characteristics of the post-Napoleonic scene. In the late nineteenth century, military thinking remained dominated by the German Wars of Unification (1864–1871), which had been short and decided by great battles of annihilation. In Vom Kriege (On War, 1832) Carl von Clausewitz (1780–1831) had defined decisive battle as a victory which had political results

... the object is to overthrow the enemy, to render him politically helpless or militarily impotent, thus forcing him to sign whatever peace we please.

— Clausewitz[1]

Niederwerfungsstrategie, (prostration strategy, later termed Vernichtungsstrategie (destruction strategy) a policy of seeking decisive victory) replaced the slow, cautious approach to war that had been overturned by Napoleon. German strategists judged the defeat of the Austrians in the Austro-Prussian War (14 June – 23 August 1866) and the French imperial armies in 1870, as evidence that a strategy of decisive victory could still succeed.[1]

Franco-Prussian War

Field Marshal Helmuth von Moltke the Elder (1800–1891), led the armies of the North German Confederation that achieved a speedy and decisive victory against the armies of the Second French Empire (1852–1870) of Napoleon III (1808–1873). On 4 September, after the Battle of Sedan (1 September 1870), there had been a republican coup d'état and the installation of a Government of National Defence (4 September 1870 – 13 February 1871), that declared guerre à outrance (war to the uttermost).[2] From September 1870 – May 1871, the French Army confronted Moltke (the Elder) with new, improvised armies. The French destroyed bridges, railways, telegraphs and other infrastructure; food, livestock and other material was evacuated to prevent it falling into German hands. A levée en masse was promulgated on 2 November and by February 1871, the republican army had increased to 950,200 men. Despite inexperience, lack of training and a shortage of officers and artillery, the size of the new armies forced Moltke (the Elder) to divert large forces to confront them, while still besieging Paris, isolating French garrisons in the rear and guarding lines of communication from francs-tireurs (irregular military forces).[2]

Volkskrieg

The Germans had defeated the forces of the Second Empire by superior numbers and then found the tables turned; only their superior training and organisation had enabled them to capture Paris and dictate peace terms.[2] Attacks by francs-tireurs forced the diversion of 110,000 men to guard railways and bridges, which put great strain on Prussian manpower. Moltke (the Elder) wrote later,

The days are gone by when, for dynastical ends, small armies of professional soldiers went to war to conquer a city, or a province, and then sought winter quarters or made peace. The wars of the present day call whole nations to arms.... The entire financial resources of the State are appropriated to military purposes....

— Moltke the Elder[3]

He had already written, in 1867, that French patriotism would lead them to make a supreme effort and use all their national resources. The quick victories of 1870 led Moltke (the Elder) to hope that he had been mistaken but by December, he planned an Exterminationskrieg against the French population by taking the war into the south, once the size of the Prussian Army had been increased by another 100 battalions of reservists. Moltke intended to destroy or capture the remaining resources which the French possessed, against the protests of the German civilian authorities, who after the fall of Paris, negotiated a quick end to the war.[4]

Colmar von der Goltz (1843–1916) and other military thinkers, like Fritz Hoenig in Der Volkskrieg an der Loire im Herbst 1870 (The People's War in the Loire Valley in Autumn 1870, 1893–1899) and Georg von Widdern in Der Kleine Krieg und der Etappendienst (Petty Warfare and the Supply Service, 1892–1907), called the short-war belief of mainstream writers like Friedrich von Bernhardi (1849–1930) and Hugo von Freytag-Loringhoven (1855–1924) an illusion. They saw the longer war against the improvised armies of the French republic, the indecisive battles of the winter of 1870–1871 and the Kleinkrieg against francs-tireurs on the lines of communication, as better examples of the nature of modern war. Hoenig and Widdern conflated the old sense of Volkskrieg as a partisan war, with a newer sense of a war between industrialised states, fought by nations-in-arms and tended to explain French success by reference to German failings, implying that fundamental reforms were unnecessary.[5]

In Léon Gambetta und die Loirearmee (Leon Gambetta and the Army of the Loire, 1874) and Leon Gambetta und seine Armeen (Leon Gambetta and his Armies, 1877), Goltz wrote that Germany must adopt ideas used by Léon Gambetta, by improving the training of Reserve and Landwehr officers, to increase the effectiveness of the Etappendienst (supply service troops). Goltz advocated the conscription of every able-bodied man and a reduction of the period of service to two years (a proposal that got him sacked from the Great General Staff but was then introduced in 1893) in a nation-in-arms. The mass army would be able to compete with armies raised on the model of the improvised French armies and be controlled from above, to avoid the emergence of a radical and democratic people's army. Goltz maintained the theme in other publications up to 1914, notably in Das Volk in Waffen (The People in Arms, 1883) and used his position as a corps commander from 1902 to 1907 to implement his ideas, particularly in improving the training of Reserve officers and creating a unified youth organisation, the Jungdeutschlandbund (Young Germany League) to prepare teenagers for military service.[6]

Ermattungsstrategie

The Strategiestreit (strategy debate) was a public and sometimes acrimonious argument after Hans Delbrück (1848–1929), challenged the orthodox army view and its critics. Delbrück was editor of the Preußische Jahrbücher (Prussian Annals), author of Die Geschichte der Kriegskunst im Rahmen der politischen Geschichte (The History of the Art of War within the Framework of Political History; four volumes 1900–1920) and professor of modern history at the Humboldt University of Berlin from 1895. General Staff historians and commentators like Friedrich von Bernhardi, Rudolph von Caemmerer, Max Jähns and Reinhold Koser, believed that Delbrück was challenging the strategic wisdom of the army.[7] Delbrück had introduced Quellenkritik/Sachkritik (source criticism) developed by Leopold von Ranke, into the study of military history and attempted a reinterpretation of Vom Kriege (On War). Delbrück wrote that Clausewitz had intended to divide strategy into Vernichtungsstrategie (strategy of destruction) or Ermattungsstrategie (strategy of exhaustion) but had died in 1830 before he could revise the book.[8]

Delbrück wrote that Frederick the Great had used Ermattungsstrategie during the Seven Years' War (1754/56–1763) because eighteenth century armies were small and made up of professionals and pressed men. The professionals were hard to replace and the conscripts would run away if the army tried to live off the land, operate in close country or pursue a defeated enemy, in the manner of the later armies of the Coalition Wars. Dynastic armies were tied to magazines for supply, which made them incapable of fulfilling a strategy of annihilation.[7] Delbrück analysed the European alliance system that had developed since the 1890s, the Boer War (11 October 1899 – 31 May 1902) and the Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905) and concluded that the rival forces were too well-balanced for a quick war. The growth in the size of armies made a swift victory unlikely and British intervention would add a naval blockade to the rigours of an indecisive land war. Germany would face a war of attrition, similar to the view Delbrück had formed of the Seven Years' War. By the 1890s, the Strategiestreit had entered public discourse, when soldiers like the two Moltkes, also doubted the possibility of a quick victory in a European war. The German army was forced to examine its assumptions about war because of this dissenting view and some writers moved closer to Delbrück's position. The debate provided the Imperial German Army with a fairly familiar alternative to Vernichtungsstrategie, after the opening campaigns of 1914.[9]

Moltke (the Elder)

Deployment plans, 1871–1872 to 1890–1891

Assuming French hostility and a desire to recover Alsace–Lorraine, Moltke (the Elder) drew up a deployment plan for 1871–1872, expecting that another rapid victory could be achieved but the French introduced conscription in 1872. By 1873, Moltke thought that the French army was too powerful to be defeated quickly and in 1875, Moltke considered a preventive war but did not expect an easy victory. The course of the second period of the Franco-Prussian War and the example of the Wars of Unification had prompted Austria-Hungary to begin conscription in 1868 and Russia in 1874. Moltke assumed that in another war, Germany would have to fight a coalition of France and Austria or France and Russia. Even if one opponent was quickly defeated, the victory could not be exploited before the Germans would have to redeploy their armies against the second enemy. By 1877, Moltke was writing war plans with provision for an incomplete victory, in which diplomats negotiated a peace, even if it meant a return to the Status quo ante bellum and in 1879, the deployment plan reflected pessimism over the possibility of a Franco-Russian alliance and progress made by the French fortification programme.[10]

Despite international developments and his doubts about Vernichtungsstrategie, Moltke retained the traditional commitment to Bewegungskrieg (war of manoeuvre) and an army trained to fight ever-bigger battles. A decisive victory might no longer be possible but success would make a diplomatic settlement easier. Growth in the size and power of rival European armies increased the pessimism with which Moltke contemplated another war and on 14 May 1890 he gave a speech to the Reichstag, saying that the age of Volkskrieg had returned. According to Ritter (1969) the contingency plans from 1872 to 1890 were his attempts to resolve the problems caused by international developments, by adopting a strategy of the defensive, after an opening tactical offensive, to weaken the opponent, a change from Vernichtungsstrategie to Ermattungsstrategie. Foerster (1987) wrote that Moltke wanted to deter war altogether and that his calls for a preventive war diminished, peace would be preserved by the maintenance of a powerful German army instead. In 2005, Foley wrote that Foerster had exaggerated and that Moltke still believed that success in war was possible, even if incomplete and that it would make peace easier to negotiate. The possibility that a defeated enemy would not negotiate, was something that Moltke (the Elder) did not address.[11]

Schlieffen

In February 1891, Schlieffen was appointed to the post of Chief of the Großer Generalstab (Great General Staff), the professional head of the Kaiserheer (Deutsches Heer [German Army]). The post had lost influence to rival institutions in the German state because of the machinations of Alfred von Waldersee (1832–1904), who had held the post from 1888 to 1891 and had tried to use his position as a political stepping stone.[12][a] Schlieffen was seen as a safe choice, being junior, anonymous outside the General Staff and with few interests outside the army. Other governing institutions gained power at the expense of the General Staff and Schlieffen had no following in the army or state. The fragmented and antagonistic character of German state institutions made the development of a grand strategy most difficult, because no institutional body co-ordinated foreign, domestic and war policies. The General Staff planned in a political vacuum and Schlieffen's weak position was exacerbated by his narrow military view.[13]

In the army, organisation and theory had no obvious link with war planning and institutional responsibilities overlapped. The General Staff devised deployment plans and its chief became de facto Commander-in-Chief in war but in peace, command was vested in the commanders of the twenty army corps districts. The corps district commanders were independent of the General Staff Chief and trained soldiers according to their own devices. The federal system of government in the German empire included ministries of war in the constituent states, which controlled the forming and equipping of units, command and promotions. The system was inherently competitive and became more so after the Waldersee period, with the likelihood of another Volkskrieg, a war of the nation in arms, rather than the few European wars fought by small professional armies after 1815.[14] Schlieffen concentrated on matters he could influence and pressed for increases in the size of the army and the adoption of new weapons. A big army would create more choices about how to fight a war and better weapons would make the army more formidable. Mobile heavy artillery could offset numerical inferiority against a Franco–Russian coalition and smash quickly fortified places. Schlieffen tried to make the army more operationally capable so that it was better than its potential enemies and could achieve a decisive victory.[15]

Schlieffen continued the practice of staff rides (Stabs-Reise) tours of territory where military operations might take place and war games, to teach techniques to command a mass conscript army. The new national armies were so huge that battles would be spread over a much greater space than in the past and Schlieffen expected that army corps would fight Teilschlachten (battle segments) equivalent to the tactical engagements of smaller dynastic armies. Teilschlachten could occur anywhere, as corps and armies closed with the opposing army and became a Gesamtschlacht (complete battle), in which the significance of the battle segments would be determined by the plan of the commander in chief, who would give operational orders to the corps,

The success of battle today depends more on conceptual coherence than on territorial proximity. Thus, one battle might be fought in order to secure victory on another battlefield.

— Schlieffen, 1909[16]

in the former manner to battalions and regiments. War against France (1905), the memorandum later known as the "Schlieffen Plan", was a strategy for a war of extraordinarily big battles, in which corps commanders would be independent in how they fought, provided that it was according to the intent of the commander in chief. The commander led the complete battle, like commanders in the Napoleonic Wars. The war plans of the commander in chief were intended to organise haphazard encounter battles to make "the sum of these battles was more than the sum of the parts".[16]

Deployment plans, 1892–1893 to 1905–1906

In his war contingency plans from 1892 to 1906, Schlieffen faced the difficulty that the French could not be forced to fight a decisive battle quickly enough for German forces to be transferred to the east against the Imperial Russian Army to fight a war on two fronts, one-front-at-a-time. Driving out the French from their frontier fortifications would be a slow and costly process that Schlieffen preferred to avoid by a flanking movement through the Low Countries. In 1893, this was judged impractical because of a lack of manpower and mobile heavy artillery. In 1899, Schlieffen added the manoeuvre to German war plans, as a possibility, if the French pursued a defensive strategy. The German army was more powerful and by 1905, after the Russian defeat in Manchuria, Schlieffen judged the army to be formidable enough to make the northern flanking manoeuvre the basis of a war plan against France alone.[17]

In 1905, Schlieffen wrote that the Russo-Japanese War (8 February 1904 – 5 September 1905), had shown that the power of Russian army had been overestimated and that it would not recover quickly from the defeat. Schlieffen could contemplate leaving only a small force in the east and in 1905, wrote War against France which was taken up by his successor, Moltke (the Younger) and became the concept of the main German war plan from 1906–1914. The most of the German army would assemble in the west and the main force would be on the right (northern) wing. An offensive in the north through Belgium and the Netherlands would lead to an invasion of France and a decisive victory. Even with the windfall of the Russian defeat in the Far East in 1905 and belief in the superiority of German military thinking, Schlieffen had reservations about the strategy. Research published by Gerhard Ritter (1956, English edition in 1958) showed that the memorandum went through six drafts. Schlieffen considered other possibilities in 1905, using war games to model a Russian invasion of eastern Germany against a smaller German army.[18]

In a staff ride during the summer, Schlieffen tested a hypothetical invasion of France by most of the German army and three possible French responses; the French were defeated in each but then Schlieffen proposed a French counter-envelopment of the German right wing by a new army. At the end of the year, Schlieffen played a war game of a two-front war, in which the German army was evenly divided and defended against invasions by the French and Russians, where victory first occurred in the east. Schlieffen was open-minded about a defensive strategy and the political advantages of the Entente being the aggressor, not just the "military technician" portrayed by Ritter. The variety of the 1905 war games show that Schlieffen took account of circumstances; if the French attacked Metz and Strasbourg, the decisive battle would be fought in Lorraine. Ritter wrote that invasion was a means to an end not an end in itself, as did Terence Zuber in 1999 and the early 2000s. In the strategic circumstances of 1905, with the Russian army and the Tsarist state in turmoil after the defeat in Manchuria, the French would not risk open warfare; the Germans would have to force them out of the border fortress zone. The studies in 1905 demonstrated that this was best achieved by a big flanking manoeuvre through the Netherlands and Belgium.[19]

Schlieffen's thinking was adopted as Aufmarsch I (Deployment [Plan] I) in 1905 (later called Aufmarsch I West) of a Franco-German war, in which Russia was assumed to be neutral and Italy and Austria-Hungary were German allies. "[Schlieffen] did not think that the French would necessarily adopt a defensive strategy" in such a war, even though their troops would be outnumbered but this was their best option and the assumption became the theme of his analysis. In Aufmarsch I, Germany would have to attack to win such a war, which entailed all of the German army being deployed on the German–Belgian border to invade France through the southern Dutch province of Limburg, Belgium and Luxembourg. The deployment plan assumed that Royal Italian Army and Austro-Hungarian Army troops would defend Alsace-Lorraine (Elsaß-Lothringen).[20]

Prelude

Moltke (the Younger)

Helmuth von Moltke the Younger took over from Schlieffen as Chief of the German General Staff on 1 January 1906, beset with doubts about the possibility of a German victory in a great European war. French knowledge about German intentions might prompt them to retreat to evade an envelopment that could lead to Ermattungskrieg, a war of exhaustion and leave Germany exhausted, even if it did eventually win. A report on hypothetical French ripostes against an invasion, concluded that since the French army was six times larger than in 1870, the survivors from a defeat on the frontier could make counter-outflanking moves from Paris and Lyon against a pursuit by the German armies. Despite his doubts, Moltke (the Younger) retained the concept of a big enveloping manoeuvre, because of changes in the international balance of power. The Japanese victory in the Russo-Japanese War (1904–1905) weakened the Russian army and the Tsarist state and made an offensive strategy against France more realistic for a time.[21]

By 1910, Russian rearmament, army reforms and reorganisation, including the creation of a strategic reserve, made the army more formidable than before 1905. Railway building in Congress Poland reduced the time needed for mobilisation and a "war preparation period" was introduced by the Russians, to provide for mobilisation to begin with a secret order, reducing mobilisation time further.[21] The Russian reforms cut mobilisation time by half compared with 1906 and French loans were spent on railway building; German military intelligence thought that a programme due to begin in 1912 would lead to 6,200 mi (10,000 km) of new track by 1922. Modern, mobile artillery, a purge of older, inefficient officers and a revision of the army regulations, had improved the tactical capability of the Russian army and railway building would make it more strategically flexible, by keeping back troops from border districts, to make the army less vulnerable to a surprise-attack, moving men faster and with reinforcements available from the strategic reserve. The new possibilities enabled the Russians to increase the number of deployment plans, further adding to the difficulty of Germany achieving a swift victory in an eastern campaign. The likelihood of a long and indecisive war against Russia, made a quick success against France more important, so as to have the troops available for an eastern deployment.[21]

Moltke (the Younger) made substantial changes to the offensive concept sketched by Schlieffen in the memorandum War against France of 1905–06. The 6th and 7th Armies with VIII Corps were to assemble along the common border, to defend against a French invasion of Alsace-Lorraine. Moltke also altered the course of an advance by the armies on the right (northern) wing, to avoid the Netherlands, retaining the country as a useful route for imports and exports and denying it to the British as a base of operations. Advancing only through Belgium, meant that the German armies would lose the railway lines around Maastricht and have to squeeze the 600,000 men of the 1st and 2nd Armies through a gap 12 mi (19 km) wide, which made it vital that the Belgian railways were captured quickly and intact. In 1908, the General Staff devised a plan to take the Fortified Position of Liège and its railway junction by coup de main on the 11th day of mobilisation. Later changes reduced the time allowed to the fifth day, which meant that the attacking forces would need to get moving only hours after the mobilisation order had been given.[22]

Deployment plans, 1906–1907 to 1914–1915

Extant records of Moltke's thinking up to 1911–1912 are fragmentary and almost wholly lacking to the outbreak of war. In a 1906 staff ride Moltke sent an army through Belgium but concluded that the French would attack through Lorraine, where the decisive battle would be fought before an enveloping move from the north took effect. The right wing armies would counter-attack through Metz, to exploit the opportunity created by the French advancing beyond their frontier fortifications. In 1908, Moltke expected the British to join the French but that neither would violate Belgian neutrality, leading the French to attack towards the Ardennes. Moltke continued to plan to envelop the French near Verdun and the Meuse, rather than an advance towards Paris. In 1909, a new 7th Army with eight divisions was prepared to defend upper Alsace and to co-operate with the 6th Army in Lorraine. A transfer of the 7th Army to the right flank was studied but the prospect of a decisive battle in Lorraine became more attractive. In 1912, Moltke planned for a contingency where the French attacked from Metz to the Vosges Mountains and the Germans defended on the left (southern) wing, until all troops not needed on the right (northern) flank could move south-west through Metz against the French flank. German offensive thinking had evolved into a possible attack from the north, one through the centre or an envelopment by both wings.[23]

Aufmarsch I West

Aufmarsch I West anticipated an isolated Franco-German war, in which Germany might be assisted by an Italian attack on the Franco-Italian border and by Italian and Austro-Hungarian forces in Germany. It was assumed that France would be on the defensive because their troops would be (greatly) outnumbered. To win the war, Germany and its allies would have to attack France. After the deployment of the entire German army in the west, they would attack through Belgium and Luxembourg, with virtually all the German force. The Germans would rely on an Austro-Hungarian and Italian contingents, formed around a cadre of German troops, to hold the fortresses along the Franco-German border. Aufmarsch I West became less feasible, as the military power of the Franco-Russian alliance increased and Britain aligned with France, making Italy unwilling to support Germany. Aufmarsch I West was dropped when it became clear that an isolated Franco-German war was impossible and that German allies would not intervene.[24]

Aufmarsch II West

Aufmarsch II West anticipated a war between the Franco-Russian Entente and Germany, with Austria-Hungary supporting Germany and Britain perhaps joining the Entente. Italy was only expected to join Germany if Britain remained neutral. 80 per cent of the German army would operate in the west and 20 per cent in the east. France and Russia were expected to attack simultaneously, because they had the larger force. Germany would execute an "active defence", in at least the first operation/campaign of the war. German forces would mass against the French invasion force and defeat it in a counter-offensive, while conducting a conventional defence against the Russians. Rather than pursue the retreating French armies over the border, 25 per cent of the German force in the west (20 per cent of the German army) would be transferred to the east, for a counter-offensive against the Russian army. Aufmarsch II West became the main German deployment plan, as the French and Russians expanded their armies and the German strategic situation deteriorated, Germany and Austria-Hungary being unable to increase their military spending to match their rivals.[25]

Aufmarsch I Ost

Aufmarsch I Ost was for a war between the Franco-Russian Entente and Germany, with Austria-Hungary supporting Germany and the British Empire perhaps joining the Entente. The Kingdom of Italy was only expected to join Germany if Britain remained neutral; 60 per cent of the German army would deploy in the west and 40 per cent in the east. France and Russia would attack simultaneously, because they had the larger force and Germany would execute an "active defence", in at least the first operation/campaign of the war. German forces would mass against the Russian invasion force and defeat it in a counter-offensive, while conducting a conventional defence against the French. Rather than pursue the Russians over the border, 50 per cent of the German force in the east (about 20 per cent of the German army) would be transferred to the west, for a counter-offensive against the French. Aufmarsch I Ost became a secondary deployment plan, as it was feared a French invasion force could be too well established to be driven from Germany or at least inflict greater losses on the Germans, if not defeated sooner. The counter-offensive against France was also seen as the more important operation, since the French were less able to replace losses than Russia and it would result in a greater number of prisoners being taken.[24]

Aufmarsch II Ost

Aufmarsch II Ost was for the contingency of an isolated Russo-German war, in which Austria-Hungary might support Germany. The plan assumed that France would be neutral at first and possibly attack Germany later. If France helped Russia then Britain might join in and if it did, Italy was expected to remain neutral. About 60 per cent of the German army would operate in the west and 40 per cent in the east. Russia would begin an offensive because of its larger army and in anticipation of French involvement but if not, the German army would attack. After the Russian army had been defeated, the German army in the east would pursue the remnants. The German army in the west would stay on the defensive, perhaps conducting a counter-offensive but without reinforcements from the east.[26] Aufmarsch II Ost became a secondary deployment plan when the international situation made an isolated Russo-German war impossible. Aufmarsch II Ost had the same flaw as Aufmarsch I Ost, in that it was feared that a French offensive would be harder to defeat, if not countered with greater force, either slower as in Aufmarsch I Ost or with greater force and quicker, as in Aufmarsch II West.[27]

Plan XVII

After amending Plan XVI in September 1911, Joffre and the staff took eighteen months to revise the French concentration plan, the concept of which was accepted on 18 April 1913. Copies of Plan XVII were issued to army commanders on 7 February 1914 and the final draft was ready on 1 May. The document was not a campaign plan but it contained a statement that the Germans were expected to concentrate the bulk of their army on the Franco-German border and might cross before French operations could begin. The instruction of the Commander in Chief was that

Whatever the circumstances, it is the Commander in Chief's intention to advance with all forces united to the attack of the German armies. The action of the French armies will be developed in two main operations: one, on the right in the country between the wooded district of the Vosges and the Moselle below Toul; the other, on the left, north of a line Verdun–Metz. The two operations will be closely connected by forces operating on the Hauts de Meuse and in the Woëvre.

— Joffre[28]

and that to achieve this, the French armies were to concentrate, ready to attack either side of Metz–Thionville or north into Belgium, in the direction of Arlon and Neufchâteau.[29] An alternative concentration area for the Fourth and Fifth armies was specified, in case the Germans advanced through Luxembourg and Belgium but an enveloping attack west of the Meuse was not anticipated. The gap between the Fifth Army and the North Sea was covered by Territorial units and obsolete fortresses.[30]

Battle of the Frontiers

| Battle | Date |

|---|---|

| Battle of Mulhouse | 7–10 August |

| Battle of Lorraine | 14–25 August |

| Battle of the Ardennes | 21–23 August |

| Battle of Charleroi | 21–23 August |

| Battle of Mons | 23–24 August |

When Germany declared war, France implemented Plan XVII with five attacks, later named the Battle of the Frontiers. The German deployment plan, Aufmarsch II, concentrated German forces (less 20 per cent to defend Prussia and the German coast) on the German–Belgian border. The German force was to advance into Belgium, to force a decisive battle with the French army, north of the fortifications on the Franco-German border.[32] Plan XVII was an offensive into Alsace-Lorraine and southern Belgium. The French attack into Alsace-Lorraine resulted in worse losses than anticipated, because artillery–infantry co-operation that French military theory required, despite its embrace of the "spirit of the offensive", proved to be inadequate. The attacks of the French forces in southern Belgium and Luxembourg were conducted with negligible reconnaissance or artillery support and were bloodily repulsed, without preventing the westward manoeuvre of the northern German armies.[33]

Within a few days, the French had suffered costly defeats and the survivors were back where they began.[34] The Germans advanced through Belgium and northern France, pursuing the Belgian, British and French armies. The German armies attacking in the north reached an area 19 mi (30 km) north-east of Paris but failed to trap the Allied armies and force on them a decisive battle. The German advance outran its supplies; Joffre used French railways to move the retreating armies, re-group behind the river Marne and the Paris fortified zone, faster than the Germans could pursue. The French defeated the faltering German advance with a counter-offensive at the First Battle of the Marne, assisted by the British.[35] Moltke (the Younger) had tried to apply the offensive strategy of Aufmarsch I (a plan for an isolated Franco-German war, with all German forces deployed against France) to the inadequate western deployment of Aufmarsch II (only 80 per cent of the army assembled in the west) to counter Plan XVII. In 2014, Terence Holmes wrote,

Moltke followed the trajectory of the Schlieffen plan, but only up to the point where it was painfully obvious that he would have needed the army of the Schlieffen plan to proceed any further along these lines. Lacking the strength and support to advance across the lower Seine, his right wing became a positive liability, caught in an exposed position to the east of fortress Paris.[36]

History

Interwar

Der Weltkrieg

Work began on Der Weltkrieg 1914 bis 1918: Militärischen Operationen zu Lande (The World War [from] 1914 to 1918: Military Operations on Land) in 1919 in the Kriegsgeschichte der Großen Generalstabes (War History Section) of the Great General Staff. When the Staff was abolished by the Treaty of Versailles, about eighty historians were transferred to the new Reichsarchiv in Potsdam. As President of the Reichsarchiv, General Hans von Haeften led the project and it overseen from 1920 by a civilian historical commission. Theodor Jochim, the first head of the Reichsarchiv section for collecting documents, wrote that

... the events of the war, strategy and tactics can only be considered from a neutral, purely objective perspective which weighs things dispassionately and is independent of any ideology. [37]

The Reichsarchiv historians produced Der Weltkrieg, a narrative history (also known as the Weltkriegwerk) in fourteen volumes published from 1925 to 1944, which became the only source written with free access to the German documentary records of the war.[38]

From 1920, semi-official histories had been written by Hermann von Kuhl, the 1st Army Chief of Staff in 1914, Der Deutsche Generalstab in Vorbereitung und Durchführung des Weltkrieges (The German General Staff in the Preparation and Conduct of the World War, 1920) and Der Marnefeldzug (The Marne Campaign) in 1921, by Lieutenant-Colonel Wolfgang Foerster, the author of Graf Schlieffen und der Weltkrieg (Count Schlieffen and the World War, 1925), Wilhelm Groener, head of Oberste Heeresleitung (OHL, the wartime German General Staff) railway section in 1914, published Das Testament des Grafen Schlieffen: Operativ Studien über den Weltkrieg (The Testament of Count Schlieffen: Operational Studies of the World War) in 1929 and Gerhard Tappen, head of the OHL operations section in 1914, published Bis zur Marne 1914: Beiträge zur Beurteilung der Kriegführen bis zum Abschluss der Marne-Schlacht (Until the Marne 1914: Contributions to the Assessment of the Conduct of the War up to the Conclusion of the Battle of the Marne) in 1920.[39] The writers called the Schlieffen Memorandum of 1905–1906 an infallible blueprint and that all Moltke (the Younger) had to do to almost guarantee that the war in the west would be won in August 1914, was implement it. The writers blamed Moltke for altering the plan to increase the force of the left wing at the expense of the right, which caused the failure to defeat decisively the French armies.[40] By 1945, the official historians had also published two series of popular histories but in April, the Reichskriegsschule building in Potsdam was bombed and nearly all of the war diaries, orders, plans, maps, situation reports and telegrams usually available to historians studying the wars of bureaucratic states, were destroyed.[41]

Hans Delbrück

In his post-war writing, Delbrück held that the German General Staff had used the wrong war plan, rather than failed adequately to follow the right one. The Germans should have defended in the west and attacked in the east, following the plans drawn up by Moltke (the Elder) in the 1870s and 1880s. Belgian neutrality need not have been breached and a negotiated peace could have been achieved, since a decisive victory in the west was impossible and not worth the attempt. Like the Strategiestreit before the war, this led to a long exchange between Delbrück and the official and semi-official historians of the former Great General Staff, who held that an offensive strategy in the east would have resulted in another 1812. The war could only have been won against Germany's most powerful enemies, France and Britain. The debate between the Delbrück and Schlieffen "schools" rumbled on through the 1920s and 1930s.[42]

1940s – 1990s

Gerhard Ritter

In Sword and the Sceptre; The Problem of Militarism in Germany (1969), Gerhard Ritter wrote that Moltke (the Elder) changed his thinking to accommodate the change in warfare evident since 1871, by fighting the next war on the defensive in general,

All that was left to Germany was the strategic defensive, a defensive, however, that would resemble that of Frederick the Great in the Seven Years' War. It would have to be coupled with a tactical offensive of the greatest possible impact until the enemy was paralysed and exhausted to the point where diplomacy would have a chance to bring about a satisfactory settlement. [43]

Moltke tried to resolve the strategic conundrum of a need for quick victory and pessimism about a German victory in a Volkskrieg by resorting to Ermattungsstrategie, beginning with an offensive intended to weaken the opponent, eventually to bring an exhausted enemy to diplomacy, to end the war on terms with some advantage for Germany, rather than to achieve a decisive victory by an offensive strategy.[44] In The Schlieffen Plan (1956, trans. 1958), Ritter published the Schlieffen Memorandum and described the six drafts that were necessary before Schlieffen was satisfied with it, demonstrating his difficulty of finding a way to win the anticipated war on two fronts and that until late in the process, Schlieffen had doubts about how to deploy the armies. The enveloping move of the armies was a means to an end, the destruction of the French armies and that the plan should be seen in the context of the military realities of the time.[45]

Martin van Creveld

In 1980, Martin van Creveld concluded that a study of the practical aspects of the Schlieffen Plan was difficult, because of a lack of information. The consumption of food and ammunition at times and places are unknown, as are the quantity and loading of trains moving through Belgium, the state of repair of railway stations and data about the supplies which reached the front-line troops. Creveld thought that Schlieffen had paid little attention to supply matters, understanding the difficulties but trusting to luck, rather than concluding that such an operation was impractical. Schlieffen was able to predict the railway demolitions carried out in Belgium, naming some of the ones that caused the worst delays in 1914. The assumption made by Schlieffen that the armies could live off the land was vindicated. Under Moltke (the Younger) much was done to remedy the supply deficiencies in German war planning, studies being written and training being conducted in the unfashionable "technics" of warfare. Moltke (the Younger) introduced motorised transport companies, which were invaluable in the 1914 campaign; in supply matters, the changes made by Moltke to the concepts established by Schlieffen were for the better.[46]

Creveld wrote that the German invasion in 1914 succeeded beyond the inherent difficulties of an invasion attempt from the north; peacetime assumptions about the distance infantry armies could march were confounded. The land was fertile, there was much food to be harvested and though the destruction of railways was worse than expected, this was far less marked in the areas of the 1st and 2nd armies. Although the amount of supplies carried forward by rail cannot be quantified, enough got to the front line to feed the armies. Even when three armies had to share one line, the six trains a day each needed to meet their minimum requirements arrived. The most difficult problem was to advance railheads quickly enough to stay close enough to the armies. By the time of the Battle of the Marne, all but one German army had advanced too far from its railheads. Had the battle been won, only in the 1st Army area could the railways have been swiftly repaired; the armies further east could not have been supplied.[47]

German army transport was reorganised in 1908 but in 1914, the transport units operating in the areas behind the front line supply columns failed, having been disorganised from the start by Moltke crowding more than one corps per road, a problem that was never remedied but Creveld wrote that even so, the speed of the marching infantry would still have outstripped horse-drawn supply vehicles, if there had been more road-space; only motor transport units kept the advance going. Creveld concluded that despite shortages and "hungry days", the supply failures did not cause the German defeat on the Marne, Food was requisitioned, horses worked to death and sufficient ammunition was brought forward in sufficient quantities so that no unit lost an engagement through lack of supplies. Creveld also wrote that had the French been defeated on the Marne, the lagging behind of railheads, lack of fodder and sheer exhaustion, would have prevented much of a pursuit. Schlieffen had behaved "like an ostrich" on supply matters which were obvious problems and although Moltke remedied many deficiencies of the Etappendienst (the German army supply system), only improvisation got the Germans as far as the Marne; Creveld wrote that it was a considerable achievement in itself.[48]

John Keegan

In 1998, John Keegan wrote that Schlieffen had desired to repeat the frontier victories of the Franco-Prussian War in the interior of France but that fortress-building since that war had made France harder to attack; a diversion through Belgium remained feasible but this "lengthened and narrowed the front of advance". A corps took up 18 mi (29 km) of road and 20 mi (32 km) was the limit of a day's march; the end of a column would still be near the beginning of the march, when the head of the column arrived at the destination. More roads meant smaller columns but parallel roads were only about 0.62–1.24 mi (1–2 km) apart and with thirty corps advancing on a 190 mi (300 km) front, each corps would have about 6.2 mi (10 km) width, which might contain seven roads. This number of roads was not enough for the ends of marching columns to reach the heads by the end of the day; this physical limit meant that it would be pointless to add troops to the right wing.[49]

Schlieffen was realistic and the plan reflected mathematical and geographical reality; expecting the French to refrain from advancing from the frontier and the German armies to fight great battles in the hinterland was found to be wishful thinking. Schlieffen pored over maps of Flanders and northern France, to find a route by which the right wing of the German armies could move swiftly enough to arrive within six weeks, after which the Russians would have overrun the small force guarding the eastern approaches of Berlin.[49] Schlieffen wrote that commanders must hurry on their men, allowing nothing to stop the advance and not detach forces to guard by-passed fortresses or the lines of communication, yet they were to guard railways, occupy cities and prepare for contingencies, like British involvement or French counter-attacks. If the French retreated into the "great fortress" into which France had been made, back to the Oise, Aisne, Marne or Seine, the war could be endless.[50]

Schlieffen also advocated an army (to advance with or behind the right wing), bigger by 25 per cent, using untrained and over-age reservists. The extra corps would move by rail to the right wing but this was limited by railway capacity and rail transport would only go as far the German frontiers with France and Belgium, after which the troops would have to advance on foot. The extra corps appeared at Paris, having moved further and faster than the existing corps, along roads already full of troops. Keegan wrote that this resembled a plan falling apart, having run into a logical dead end. Railways would bring the armies to the right flank, the Franco-Belgian road network would be sufficient for them to reach Paris in the sixth week but in too few numbers to defeat decisively the French. Another 200,000 men would be necessary for which there was no room; Schlieffen's plan for a quick victory was fundamentally flawed.[50]

1990s–present

German reunification

In the 1990s, after the dissolution of the German Democratic Republic, it was discovered that some Great General Staff records had survived the Potsdam bombing in 1945 and been confiscated by Soviet Military Administration in Germany authorities. About 3,000 files and 50 boxes of documents were handed over to the Bundesarchiv (German Federal Archives) containing the working notes of Reichsarchiv historians, business documents, research notes, studies, field reports, draft manuscripts, galley proofs, copies of documents, newspaper clippings and other papers. The trove shows that Der Weltkrieg is a "generally accurate, academically rigorous and straightforward account of military operations", when compared to other contemporary official accounts.[41] Six volumes cover the first 151 days of the war in 3,255 pages (40 per cent of the series). The first volumes attempted to explain why the German war plans failed and who was to blame.[51]

In 2002, RH 61/v.96, a summary of German war planning from 1893 to 1914 was discovered in records written from the late 1930s to the early 1940s. The summary was for a revised edition of the volumes of Der Weltkrieg on the Marne campaign and was made available to the public.[52] Study of pre-war German General Staff war planning and the other records, made an outline of German war-planning possible for the first time, proving many guesses wrong.[53] An inference that all of Schlieffen's war-planning was offensive, came from the extrapolation of his writings and speeches on tactical matters to the realm of strategy.[54] In 2014, Terence Holmes wrote

There is no evidence here [in Schlieffen's thoughts on the 1901 Generalstabsreise Ost (eastern war game)]—or anywhere else, come to that—of a Schlieffen credo dictating a strategic attack through Belgium in the case of a two-front war. That may seem a rather bold statement, as Schlieffen is positively renowned for his will to take the offensive. The idea of attacking the enemy’s flank and rear is a constant refrain in his military writings. But we should be aware that he very often speaks of an attack when he means counter-attack. Discussing the proper German response to a French offensive between Metz and Strasbourg [as in the later 1913 French deployment-scheme Plan XVII and actual Battle of the Frontiers in 1914], he insists that the invading army must not be driven back to its border position, but annihilated on German territory, and "that is possible only by means of an attack on the enemy’s flank and rear". Whenever we come across that formula we have to take note of the context, which frequently reveals that Schlieffen is talking about a counter-attack in the framework of a defensive strategy.[55]

and the most significant of these errors was an assumption that a model of a two-front war against France and Russia, was the only German deployment plan. The thought-experiment and the later deployment plan modelled an isolated Franco-German war (albeit with aid from German allies), the 1905 plan was one of three and then four plans available to the Great General Staff. A lesser error was that the plan modelled the decisive defeat of France in one campaign of fewer than forty days and that Moltke (the Younger) foolishly weakened the attack, by being over-cautious and strengthening the defensive forces in Alsace-Lorraine. Aufmarsch I West had the more modest aim of forcing the French to choose between losing territory or committing the French army to a decisive battle, in which it could be terminally weakened and then finished off later

The plan was predicated on a situation when there would be no enemy in the east [...] there was no six-week deadline for completing the western offensive: the speed of the Russian advance was irrelevant to a plan devised for a war scenario excluding Russia.

— Holmes[56]

and Moltke (the Younger) made no more alterations to Aufmarsch I West but came to prefer Aufmarsch II West and tried to apply the offensive strategy of the former to the latter.[57]

Robert Foley

In 2005, Robert Foley wrote that Schlieffen and Moltke (the Younger) had recently been severely criticised by Martin Kitchen, who had written that Schlieffen was a narrow-minded technocrat, obsessed with minutiae. Arden Bucholz had called Moltke too untrained and inexperienced to understand war planning, which prevented him from having a war policy from 1906 to 1911; it was the failings of both men that caused them to keep a strategy that was doomed to fail. Foley wrote that Schlieffen and Moltke (the Younger) had good reason to retain Vernichtungsstrategie as the foundation of their planning, despite their doubts as to its validity. Schlieffen had been convinced that only in a short war was there the possibility of victory and that by making the army operationally superior to its potential enemies, Vernichtungsstrategie could be made to work. The unexpected weakening of the Russian army in 1904–1905 and the exposure of its incapacity to conduct a modern war, which was expected to continue for a long time, making a short war possible again. Since the French had a defensive strategy, the Germans would have to take the initiative and invade France, which was shown to be feasible by war games in which French border fortifications were outflanked.[58]

Moltke continued with the offensive plan, after it was seen that the enfeeblement of Russian military power had been for a much shorter period than Schlieffen had expected. The substantial revival in Russian military power that began in 1910 would certainly have matured by 1922, making the Tsarist army unbeatable. The end of the possibility of a short, eastern war and the certainty of increasing Russian military power meant that Moltke had to look to the west for a quick victory, before Russian mobilisation was complete. Speed meant an offensive strategy and made doubts about the possibility of forcing defeat on the French army irrelevant. The only way to avoid becoming bogged down in the French fortress zones was by a flanking move into terrain where open warfare was possible and the German army could fight a Bewegungskrieg (a war of manoeuvre). Moltke (the Younger) used the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand on 28 June 1914, as an excuse to attempt Vernichtungsstrategie against France, before Russian rearmament deprived Germany of any hope of victory.[59]

Terence Holmes

In 2013, Holmes published a summary of his thinking about the Schlieffen Plan and the debates about it in Not the Schlieffen Plan. He wrote that people believed that the Schlieffen Plan was for a grand offensive against France to gain a decisive victory in six weeks. The Russians would be held back and then defeated with reinforcements rushed by rail from the west. Holmes wrote that no-one had produced a source showing that Schlieffen intended a huge right-wing flanking move into France, in a two-front war. The 1905 Memorandum was for War against France, in which Russia would be unable to participate. Schlieffen had thought about such an attack on two general staff rides (Generalstabsreisen) in 1904, on the staff ride of 1905 and in the deployment plan Aufmarsch West I, for 1905–06 and 1906–07, in which all of the German army fought the French. In none of these plans was a two-front war contemplated; the common view that Schlieffen thought that such an offensive would guarantee victory in a two-front war was wrong. In his last exercise critique in December 1905, Schlieffen wrote that the Germans would be so outnumbered against France and Russia, that the Germans must rely on a counter-offensive strategy against both enemies, to eliminate one as quickly as possible.[60]

In 1914, Moltke (the Younger) attacked Belgium and France with 34 corps, rather than the 48+1⁄2 corps specified in the Schlieffen Memorandum, Moltke (the Younger) had insufficient troops to advance around the west side of Paris and six weeks later, the Germans were digging-in on the Aisne. The post-war idea of a six-week timetable, derived from discussions in May 1914, when Moltke had said that he wanted to defeat the French "in six weeks from the start of operations". The deadline did not appear in the Schlieffen Memorandum and Holmes wrote that Schlieffen would have considered six weeks to be far too long to wait in a war against France and Russia. Schlieffen wrote that the Germans must "wait for the enemy to emerge from behind his defensive ramparts" and intended to defeat the French army by a counter-offensive, tested in the general staff ride west of 1901. The Germans concentrated in the west and the main body of the French advanced through Belgium into Germany. The Germans then made a devastating counter-attack on the left bank of the Rhine near the Belgian border. The hypothetical victory was achieved by the 23rd day of mobilisation; nine active corps had been rushed to the eastern front by the 33rd day for a counter-attack against the Russian armies. Even in 1905, Schlieffen thought the Russians capable of mobilising in 28 days and that the Germans had only three weeks to defeat the French, which could not be achieved by a promenade through France.[61]

The French were required by the treaty with Russia, to attack Germany as swiftly as possible but could advance into Belgium only after German troops had infringed Belgian sovereignty. Joffre had to devise a plan for an offensive that avoided Belgian territory, which would have been followed in 1914, had the Germans not invaded Belgium first. For this contingency, Joffre planned for three of the five French armies (about 60 per cent of the French first-line troops) to invade Lorraine on 14 August, to reach the river Saar from Sarrebourg to Saarbrücken, flanked by the German fortress zones around Metz and Strasbourg. The Germans would defend against the French, who would be enveloped on three sides then the Germans would attempt an encircling manoeuvre from the fortress zones to annihilate the French force. Joffre understood the risks but would have had no choice, had the Germans used a defensive strategy. Joffre would have had to run the risk of an encirclement battle against the French First, Second and Fourth armies. In 1904, Schlieffen had emphasised that the German fortress zones were not havens but jumping-off points for a surprise counter-offensive. In 1914, it was the French who made a surprise attack from the Région Fortifiée de Paris (Paris fortified zone) against a weakened German army.[62]

Holmes wrote that Schlieffen never intended to invade France through Belgium, in a war against France and Russia,

If we want to visualize Schlieffen's stated principles for the conduct of a two front war coming to fruition under the circumstances of 1914, what we get in the first place is the image of a gigantic Kesselschlacht to pulverise the French army on German soil, the very antithesis of Moltke's disastrous lunge deep into France. That radical break with Schlieffen's strategic thinking ruined the chance of an early victory in the west on which the Germans had pinned all their hopes of prevailing in a two-front war. [63]

Holmes–Zuber debate

Zuber wrote that the Schlieffen Memorandum was a "rough draft" of a plan to attack France in a one-front war, which could not be regarded as an operational plan, as the memo was never typed up, was stored with Schlieffen's family and envisioned the use of units not in existence. The "plan" was not published after the war when it was being called an infallible recipe for victory, ruined by the failure of Moltke adequately to select and maintain the aim of the offensive. Zuber wrote that if Germany faced a war with France and Russia, the real Schlieffen Plan was for defensive counter-attacks. [67][b] Holmes supported Zuber in his analysis that Schlieffen had demonstrated in his thought-experiment and in Aufmarsch I West, that 48+1⁄2 corps (1.36 million front-line troops) was the minimum force necessary to win a decisive battle against France or to take strategically important territory. Holmes asked why Moltke attempted to achieve either objective with 34 corps (970,000 first-line troops) only 70 per cent of the minimum required.[36]

In the 1914 campaign, the retreat by the French army denied the Germans a decisive battle, leaving them to breach the "secondary fortified area" from the Région Fortifiée de Verdun (Verdun fortified zone), along the Marne to the Région Fortifiée de Paris (Paris fortified zone).[36] If this "secondary fortified area" could not be overrun in the opening campaign, the French would be able to strengthen it with field fortifications. The Germans would then have to break through the reinforced line in the opening stages of the next campaign, which would be much more costly. Holmes wrote that

Schlieffen anticipated that the French could block the German advance by forming a continuous front between Paris and Verdun. His argument in the 1905 memorandum was that the Germans could achieve a decisive result only if they were strong enough to outflank that position by marching around the western side of Paris while simultaneously pinning the enemy down all along the front. He gave precise figures for the strength required in that operation: 33+1⁄2 corps (940,000 troops), including 25 active corps (active corps were part of the standing army capable of attacking and reserve corps were reserve units mobilized when war was declared and had lower scales of equipment and less training and fitness). Moltke's army, along the front from Paris to Verdun, consisted of 22 corps (620,000 combat troops), only 15 of which were active formations.

— Holmes[36]

Lack of troops made "an empty space where the Schlieffen Plan requires the right-wing (of the German force) to be". In the final phase of the first campaign, the German right-wing was supposed to be "outflanking that position (a line west from Verdun, along the Marne to Paris) by advancing west of Paris across the lower Seine" but in 1914 "Moltke's right-wing was operating east of Paris against an enemy position connected to the capital city...he had no right-wing at all in comparison with the Schlieffen Plan". Breaching a defensive line from Verdun, west along the Marne to Paris, was impossible with the forces available, something Moltke should have known.[68]

Holmes could not adequately explain this deficiency but wrote that Moltke's preference for offensive tactics was well known and thought that, unlike Schlieffen, Moltke was an advocate of the strategic offensive,

Moltke subscribed to a then fashionable belief that the moral advantage of the offensive could make up for a lack of numbers on the grounds that "the stronger form of combat lies in the offensive" because it meant "striving after positive goals".

— Holmes[69]

The German offensive of 1914 failed because the French refused to fight a decisive battle and retreated to the "secondary fortified area". Some German territorial gains were reversed by the Franco-British counter-offensive against the 1st Army (Generaloberst Alexander von Kluck) and 2nd Army (Generaloberst Karl von Bülow), on the German right (western) flank, during the First Battle of the Marne (5–12 September).[70]

Humphries and Maker

In 2013, Mark Humphries and John Maker published Germany's Western Front 1914, an edited translation of the Der Weltkrieg volumes for 1914, covering German grand strategy in 1914 and the military operations on the Western Front to early September. Humphries and Maker wrote that the interpretation of strategy put forward by Delbrück had implications about war planning and began a public debate, in which the German military establishment defended its commitment to Vernichtunsstrategie. The editors wrote that German strategic thinking was concerned with creating the conditions for a decisive (war determining) battle in the west, in which an envelopment of the French army from the north would inflict such a defeat on the French as to end their ability to prosecute the war within forty days. Humphries and Maker called this a simple device to fight France and Russia simultaneously and to defeat one of them quickly, in accordance with 150 years of German military tradition. Schlieffen may or may not have written the 1905 memorandum as a plan of operations but the thinking in it was the basis for the plan of operations devised by Moltke (the Younger) in 1914. The failure of the 1914 campaign was a calamity for the German Empire and the Great General Staff, which was disbanded by the Treaty of Versailles in 1919.[71]

Some of the writers of Die Grenzschlachten im Westen (The Frontier Battles in the West [1925]), the first volume of Der Weltkrieg, had already published memoirs and analyses of the war, in which they tried to explain why the plan failed in terms that confirmed its validity. Foerster, head of the Reichsarchiv from 1920 and reviewers of draft chapters like Groener, had been members of the Great General Staff and were part of a post-war "annihilation school".[39] Under these circumstances, the objectivity of the volume can be questioned as an instalment of the "battle of the memoirs", despite the claim in the foreword written by Foerster, that the Reichsarchiv would show the war as it actually happened (wie es eigentlich gewesen), in the tradition of Leopold von Ranke. It was for the reader to form conclusions and the editors wrote that though the volume might not be entirely objective, the narrative was derived from documents lost in 1945. The Schlieffen Memorandum of 1905 was presented as an operational idea, which in general was the only one that could solve the German strategic dilemma and provide an argument for an increase in the size of the army. The adaptations made by Moltke were treated in Die Grenzschlachten im Westen, as necessary and thoughtful sequels of the principle adumbrated by Schlieffen in 1905 and that Moltke had tried to implement a plan based on the 1905 memorandum in 1914. The Reichsarchiv historians's version showed that Moltke had changed the plan and altered its emphasis because it was necessary in the conditions of 1914.[72]

The failure of the plan was explained in Der Weltkrieg by showing that command in the German armies was often conducted with vague knowledge of the circumstances of the French, the intentions of other commanders and the locations of other German units. Communication was botched from the start and orders could take hours or days to reach units or never arrive. Auftragstaktik, the decentralised system of command that allowed local commanders discretion within the commander's intent, operated at the expense of co-ordination. Aerial reconnaissance had more influence on decisions than was sometimes apparent in writing on the war but it was a new technology, the results of which could contradict reports from ground reconnaissance and be difficult for commanders to resolve. It always seemed that the German armies were on the brink of victory, yet the French kept retreating too fast for the German advance to surround them or cut their lines of communication. Decisions to change direction or to try to change a local success into a strategic victory were taken by army commanders ignorant of their part in the OHL plan, which frequently changed. Der Weltkrieg portrays Moltke (the Younger) in command of a war machine "on autopilot", with no mechanism of central control.[73]

Aftermath

Analysis

In 2001, Hew Strachan wrote that it is a cliché that the armies marched in 1914 expecting a short war, because many professional soldiers anticipated a long war. Optimism is a requirement of command and expressing a belief that wars can be quick and lead to a triumphant victory, can be an essential aspect of a career as a peacetime soldier. Moltke (the Younger) was realistic about the nature of a great European war but this conformed to professional wisdom. Moltke (the Elder) was proved right in his 1890 prognostication to the Reichstag, that European alliances made a repeat of the successes of 1866 and 1871 impossible and anticipated a war of seven or thirty years' duration. Universal military service enabled a state to exploit its human and productive resources to the full but also limited the causes for which a war could be fought; Social Darwinist rhetoric made the likelihood of surrender remote. Having mobilised and motivated the nation, states would fight until they had exhausted their means to continue.[74]

There had been a revolution in firepower since 1871, with the introduction of breech-loading weapons, quick-firing artillery and the evasion of the effects of increased firepower, by the use of barbed wire and field fortifications. The prospect of a swift advance by frontal assault was remote; battles would be indecisive and decisive victory unlikely. Major-General Ernst Köpke, the Generalquartiermeister of the German army in 1895, wrote that an invasion of France past Nancy would turn into siege warfare with no quick and decisive victory. Emphasis on operational envelopment came from the knowledge of a likely tactical stalemate. The problem for the German army was that a long war implied defeat, because France, Russia and Britain, the probable coalition of enemies, were far more powerful. The role claimed by the German army, as the anti-socialist foundation on which the social order was based, also made the army apprehensive about the internal strains that would be generated by a long war.[75]

Schlieffen was faced by a contradiction between strategy and national policy and advocated a short war based on Vernichtungsstrategie, because of the probability of a long one. Given the recent experience of military operations in the Russo-Japanese War, Schlieffen resorted to an assumption that international trade and domestic credit could not bear a long war and this tautology justified Vernichtungsstrategie. Grand strategy, a comprehensive approach to warfare that took in economics and politics as well as military considerations, was beyond the capacity of the Great General Staff (as it was among the general staffs of rival powers). Moltke (the Younger) found that he could not dispense with Schlieffen's offensive concept, because of the objective constraints that had led to it. Moltke was less certain and continued to plan for a short war, while urging the civilian administration to prepare for a long one, which only managed to convince people that he was indecisive.[76]

By 1913, Moltke (the Younger) had a staff of 650 men, to command an army five times greater than that of 1870, which would move on double the railway mileage [56,000 mi (90,000 km)], relying on delegation of command, to cope with the increase in numbers and space and the decrease in the time available to get results. Auftragstaktik led to the stereotyping of decisions at the expense of flexibility to respond to the unexpected, something increasingly likely after first contact with the opponent. Moltke doubted that the French would conform to Schlieffen's more optimistic assumptions. In May 1914 he said, "I will do what I can. We are not superior to the French." and on the night of 30/31 July 1914, remarked that if Britain joined the anti-German coalition, no-one could foresee the duration or result of the war.[77]

In 2006 the Center for Military History and Social Sciences of the Bundeswehr) published a collection of essays derived from a conference in 2004 held at Potsdam to discuss Terry Zuber's conclusion that there was no Schlieffen Plan. Had Zuber accurately interpreted his sources and were they adequate for his conclusions? The participants produced a comparative analysis of the war plans of the 1914 belligerents and Switzerland. In the Introduction to the volume, Hans Ehlert, Michael Epkenhans and Gerhard Gross wrote that Zuber's conclusion that the plan was a myth was a surprise, because many German generals had recorded at the time that the campaign in August and September had been based on Schlieffen. Falkenhayn had made a diary note on 10 September 1914 that,

One is left speechless hearing those instructions. They only prove one thing with certainty, that our General Staff has completely lost its head. Schlieffen's notes have come to an end and so have the wits of Moltke.[78]

The Bavarian representative at the Great General Staff, General Karl Ritter von Wenninger wrote to Munich that

Schlieffen's operational plan of 1909 has been implemented, as i heard, without significant changes and even after the initial confrontation with the enemy.[78]

Wenninger went on to write that only the final encirclement by the northern and southern wings of the German force had not been achieved. After the Battle of the Marne, Wenninger wrote on 16 February that

Falkenhayn without doubt has his own thoughts, while Moltke and his subordinates were completely sterile. They could only turn the handle and run Schlieffen's film and were clueless and beside themselves when the roll got stuck.[79]

Zuber maintained his thesis that the plan was a post-war fabrication by former General Staff officers to shift the blame for a lost war. Annika Mombauer wrote that Zuber had overlooked the intimate connexion between the military and political worlds and that trying to explain the war as the result of Schlieffen and Moltke's desire for war risked falling for the post-war apologetics of the General Staff that Schlieffen had created a plan that would inevitably bring victory. Robert Foley described the substantial changes in Germany's strategic circumstances between 1905 and 1914 which compelled German planners to prepare for a quick one-front war which could only be fought against France, the evidence for which lay in Schlieffen's staff rides, of which Zuber had taken too little account.[80]

Gerhard Gross wrote that the sources used by Zuber were inadequate for his conclusions. Zuber had not looked at published excerpts from the pre-war Aufmarschanweisungen (deployment commands) and the papers of General of Artillery, Friedrich von Boetticher, which included copies of original Schlieffen papers and correspondence with Schlieffen's friends and colleagues. The documents showed that Zuber had misunderstood Schlieffen's operational thinking, which was based on obtaining a decisive victory against the French through envelopment on French territory but in a much less dogmatic way than had been thought. Gross agreed with Zuber that the Denkschrift of 1905 was not an operational plan for a war against France or a detailed plan for a two-front war.[80] Dieter Storz wrote that plans and reality rarely match and that the extant Bavarian records bear out the basis of Schlieffen's thinking, that the French armies were to be outflanked by the right wing. Günter Kronenbitter analysed the deployment plans of Austria-Hungary and that despite the alliance and relationship between the German and Austrian general staffs there was no unified operational plan.[81]

The Zuber thesis was the catalyst for a debate that suggested new questions and answers and turned up new sources. Zuber may not have convinced scholars but was a considerable catalyst for research. Zuber withheld permission for his chapter to be included in the English translation. The book includes the German deployment plans, long thought lost, which show Schlieffen's operational assumptions and that the emphasis on envelopment was continued by Moltke, despite his changes of other aspects of the deployment plans.[82]

In 2009, David Stahel wrote that the Clausewitzian culminating point (a theoretical watershed at which the strength of a defender surpasses that of an attacker) of the German offensive occurred before the Battle of the Marne, because the German right (western) flank armies east of Paris, were operating 62 mi (100 km) from the nearest rail-head, requiring week-long round-trips by underfed and exhausted supply horses, which led to the right wing armies becoming disastrously short of ammunition. Stahel wrote that contemporary and subsequent German assessments of Moltke's implementation of Aufmarsch II West in 1914, did not criticise the planning and supply of the campaign, even though these were instrumental to its failure and that this failure of analysis had a disastrous sequel, when the German armies were pushed well beyond their limits in Operation Barbarossa, during 1941.[83]

In 2015, Holger Herwig wrote that Army deployment plans were not shared with the Imperial German Navy, Foreign Office, the Chancellor, the Austro-Hungarians or the Army commands in Prussia, Bavaria and the other German states. No one outside the Great General Staff could point out problems with the deployment plan or make arrangements. "The generals who did know about it counted on it giving a quick victory within weeks—if that did not happen there was no 'Plan B'".[84]

See also

- Manstein Plan (Second World War plan with similarities)

Notes

- ^ On taking up the post, Schlieffen had been made to reprimand publicly Waldersee's subordinates.[12]